There was a period during the climate change debate—largely gone these days, I think—where skeptics were constantly coming up with new, scientific-sounding arguments against the idea of manmade warming. Typically, the claims were just technical enough that it was hard for lay readers like me to evaluate them, which meant they hung around in the air (and Fox News) until some climatologist took a break from real work to dive in and figure out what was going on. Almost without exception, these quasi-scientific arguments turned out to be wrong, usually egregiously so.

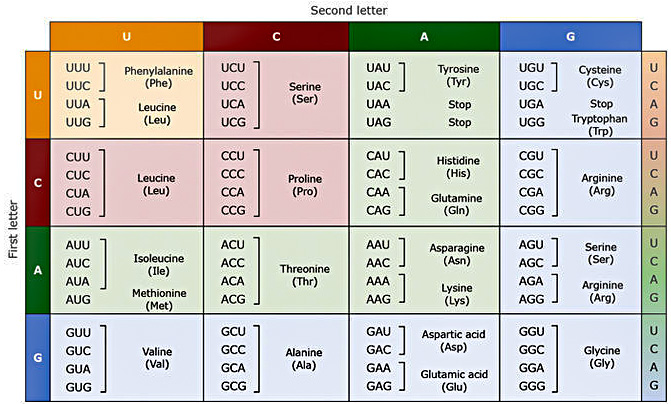

I wonder if we're entering a similar stage with proponents of the lab leak hypothesis? In the Wall Street Journal today, a pair of scientists argue that there's a specific location in the coronavirus genome that's often used in gain-of-function research. In this location, researchers splice in a code that generates two arginine amino acids in a row. There are six codes for arginine and therefore 35 possible combinations that will produce two in a row, and in the CoV-2 genome the combination turns out to be the rarest and least likely to occur in nature (a "double CGG"). It is, however, the most common in gain-of-function research because it's handy and easily available.

Is this true? How would I know? There are, of course, reasons to be cautious:

- This seems like fairly obvious stuff to a virologist. Surely someone would have mentioned this before if it were genuinely suspicious.

- The authors of the piece are a retired physicist and a physician/author who's been leading the lab leak hypothesis for a long time. No virologists signed onto this.

- The piece was published on the op-ed page, not the news pages.

So . . . there's probably nothing to this. But it will now swirl around among conservatives until it's conclusively debunked, and probably even after that. In any case, someone needs to get cracking on this.