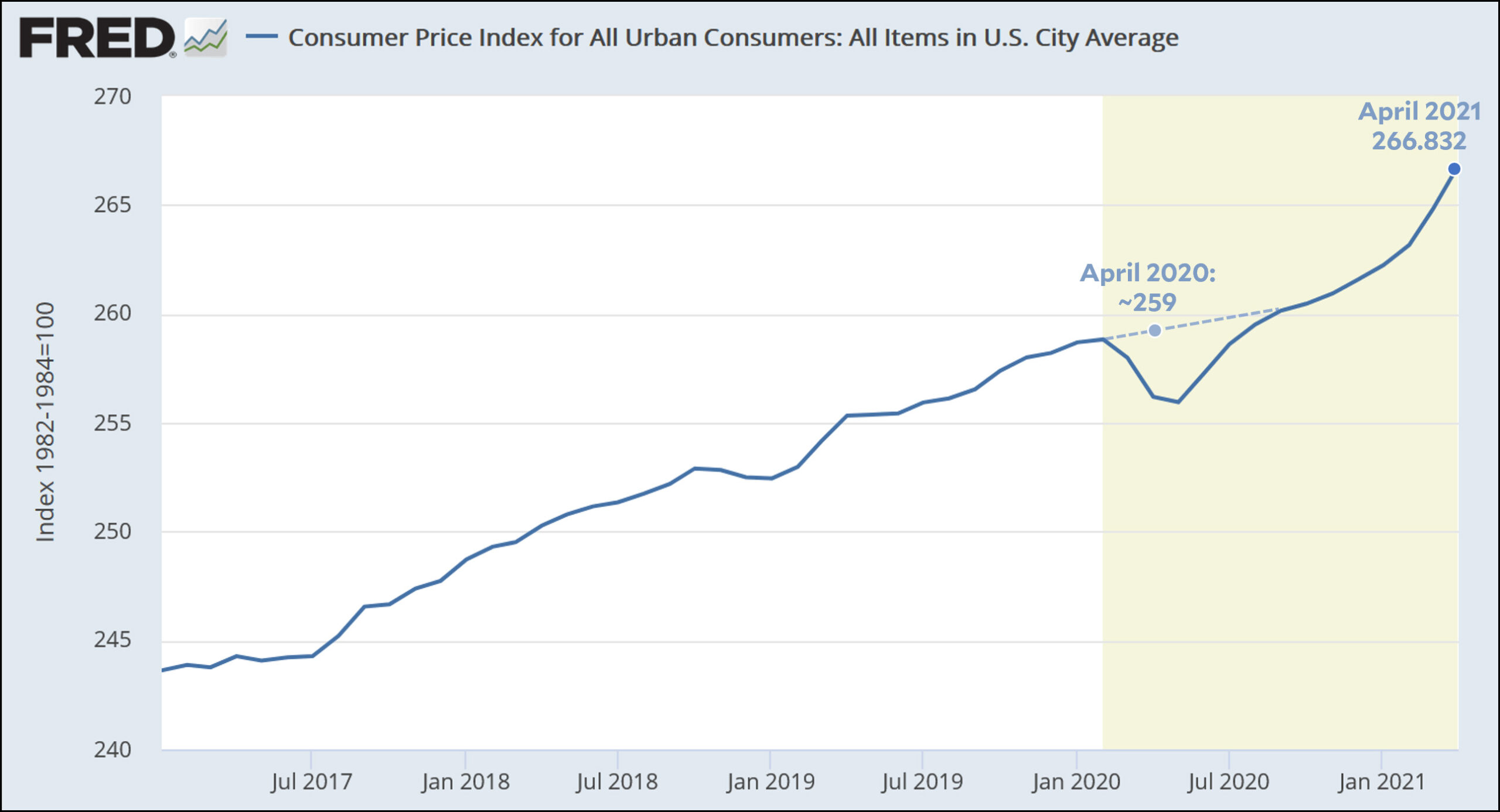

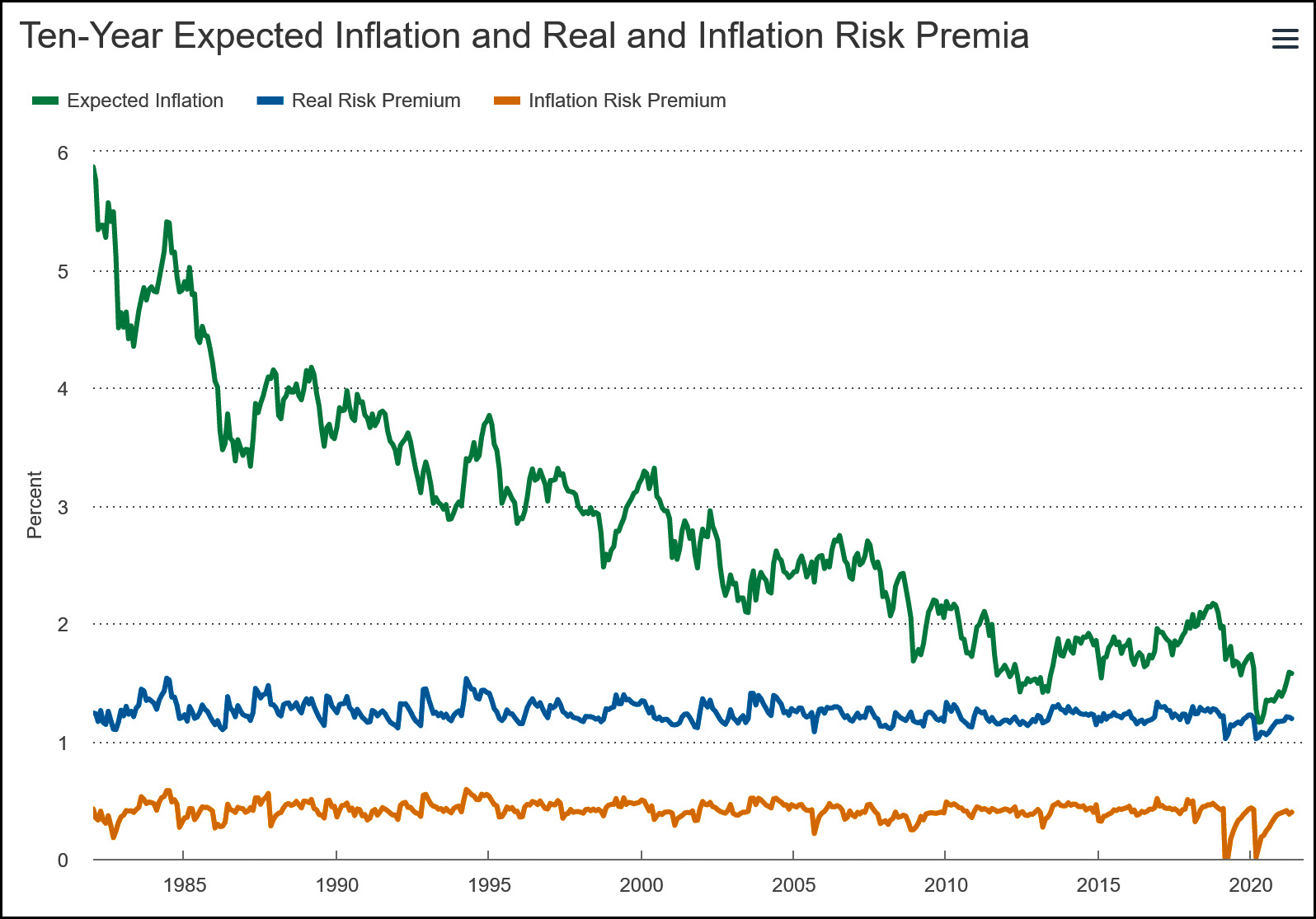

For those of you interested in a non-panicked look at inflation, the Cleveland Fed has been forecasting 10-year inflation expectations for the past forty years. Here's their entire time series:

These forecasts have been pretty accurate. Obviously there's a fair amount of noise in the data, and no forecast can account for recessions and pandemics ten years in the future, but generally speaking the Cleveland Fed forecasts are within about one percentage point of how things turn out ten years later. Right now they're forecasting future inflation at about 1.6%.

Other measures of inflation expectations, based on daily movements of Treasury rates, showed almost no movement today after the latest inflation figures were announced. Whatever the pundits are saying, the market doesn't seem to think today's figures meant much of anything at all. The 5/5 forward rate, for example, has been rising all year but dropped slightly today from 2.38% to 2.36%.

Bottom line: as with every other economic indicator, everyone should chill. Daily and monthly movements just don't mean anything, especially during a turbulent period like we're going through now. Over the next few months inflation will stabilize, the economy will grow, people will all get back to work, and everything will be fine.