Here's a headline from today's Wall Street Journal:

Higher Prices Leave Consumers Feeling the Pinch

Rising costs for everything from fresh fruit to freezers are shaping purchase decisions

The text of the article is the usual nonsense, so I won't bother describing it. Instead, here are actual inflation rates of nine broad categories of goods:

We already know that these inflation rates are artificially high because they're being compared to March 2020, which was artificially low. But even at that, they're in the range of -4% to 4% with the sole exception of transportation (primarily cars). Food at home is up 3.3%, which isn't enough to "feel the pinch" even if it were real.

But there's also another way of looking at things. Here's a list of 30 randomly chosen detailed items:

So here's what happens: Everyone notices that bacon, apples, ground beef, and whole chickens are noticeably more expensive than they used to be. But they don't notice that bananas and butter and tomatoes are less expensive. Homo sapiens being what we are—i.e., bad at on-the-run arithmetic—we conclude that prices are skyrocketing. Did you see what I had to pay for a pound of bacon!

(And even that's a mirage. Remember that these prices are artificially high because the base year for comparison is 2020. A closer look using 2019 as the base year reveals that bacon is actually up only 3.5% annually over the past two years. The entire category of food at home is up 2.2% annually over the past two years, about the same as overall inflation.)

So what explains the media's endless focus on allegedly skyrocketing prices? I don't really know. I have an old-fashioned belief that the media should be informative and truthful, knocking down popular beliefs if they turn out to be wrong. In this case, the popular belief that prices are skyrocketing is wrong. And yet instead of explaining why, the media produces story after story pandering to the misguided beliefs of its readers. Why?

POSTSCRIPT: It's possible, of course, that prices really are skyrocketing and the Bureau of Labor Statistics is miscalculating it. But if that's the case, there's a great story to be written about the BLS and I haven't seen it yet.

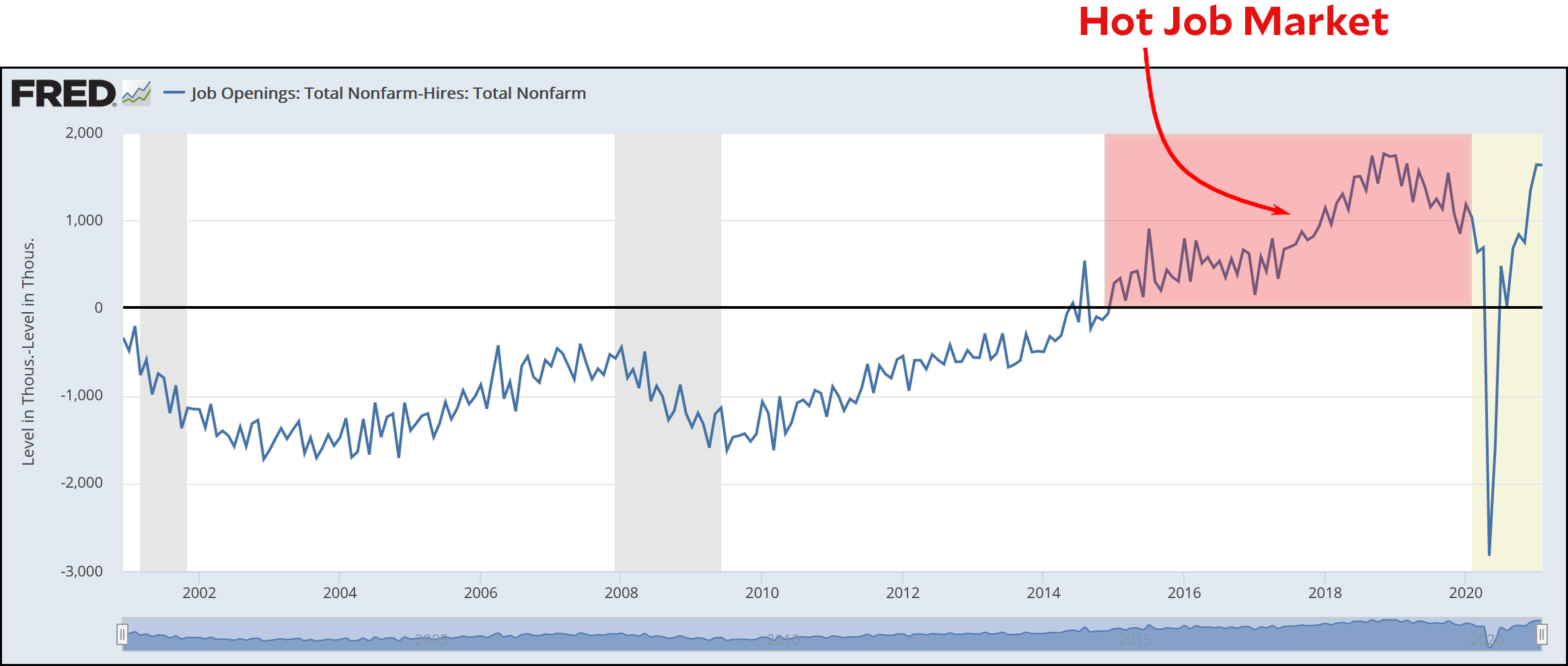

POSTSCRIPT 2: Plus there's this:

Personal income has soared! It's up by $13,000 over last year. So who cares if bacon is up a few cents? I wonder why no one reports this?

(Answer: Because it's as fake as the supposedly skyrocketing food prices. The apparent increase is due to benefits from the January rescue bill that have been annualized, not permanent income from salaries. This is what happens when you can cherry pick starting and ending points.)