Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through April 21. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Cats, charts, and politics

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through April 21. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Here is the cumulative number of COVID-19 deaths for each state (plus DC) through today. It's adjusted for population, and the ten biggest states are shown in red.

This is not a fuchsia, it is a fuchsia-flowered gooseberry, aka Ribes speciosum, which is native to California. Judging from its Wikipedia entry, it is of basically no interest at all.

What is money? Don't feel bad if you can't answer since no one else can either. Roughly speaking, though, money is an accounting mechanism for keeping track of debt, with its value ultimately backed up by a central government's willingness to accept it for tax payments. Beyond that, there are several attributes that, while not absolutely necessary, are very handy for money to have:

There are others, but you get the idea. So is Bitcoin money? Not really. Mining doesn't represent debt of any kind, it's simply a mechanism that doles out coins on a semi-random algorithmic schedule. Nor do any governments accept it for payment of taxes. It's not stable, it's not widely accepted, and it's not especially liquid. On the bright side, it's hard to counterfeit and easy to carry around.

What else shares these attributes? Rare stamps and coins come close, though they're harder to carry around since they're physical objects. But that could be pretty easily solved by creating an index of stamp and coin values that act as the basis for a blockchain.

Alternately, it could be old masters. Or tulips. Or baseball cards.

In other words, Bitcoin has few of the attributes of money but all the attributes of a collectible. And because it's the original cryptocurrency it's more sought after than, say, Ethereum, the way a 1952 Mickey Mantle is worth more than a 1951 Willie Mays. And both are more valuable than a Tom Egan rookie card, sort of the Dogecoin of baseball cards.

Bitcoin fans like to insist that it's money, but that's a serious category mistake that does nothing but cause confusion. As money, it has lots of drawbacks and solves very few problems that ordinary money doesn't already solve. Even its strongest selling point, absolute privacy, is mostly a lie, since nearly all Bitcoin is traded through central exchanges that are regulated by national governments. You don't have to use a central exchange if you have the technical chops to trade it yourself, but that's a pain in the ass and makes Bitcoin even less money-like than it already was.

Why am I pointing this out? Because many rational people don't understand Bitcoin. It seems obviously ridiculous. But that's only if you continue to think of it as a new form of money. If, instead, you think of it as a collectible, it suddenly makes a lot more sense. After all, there are lots of rare things that are collectible and lots of rare things that aren't. It's pretty random, and different collectibles go in and out of style. Remember when Beanie Babies were hot? Or Pez dispensers? There's no why about collectibles. They're just reflections of weird human foibles.

Once you make this mental adjustment you will no longer be confused about Bitcoin. It's a collectible that's gotten a lot of hype. Maybe it will stay valuable, the way rare stamps and coins have stayed valuable for a long time, or maybe, like Beanie Babies, it won't. But whichever turns out to be the case, it means nothing profound about the future of money. Bitcoin is just another collectible that will go up and down at the whims of its fans. Capiche?

Just as the verdict in the Derek Chauvin case was coming down on Tuesday, another high-profile police shooting of a Black person was taking place in Columbus, Ohio. But this case resolved very differently than the Chauvin case. Police had been called to a house where a fight was taking place and body cam video of the incident was released almost immediately. Here's what it showed:

The girl wearing black, identified as 16-year-old Ma’Khia Bryant, has a knife out and is obviously about to stab the girl wearing pink. A police officer on the scene shot Bryant four times before she could do any harm.

By American standards this was a righteous shooting. The police officer did the right thing and will certainly not be in any trouble over it.

But looking at this a little more broadly suggests that maybe American standards aren't very good. Police are trained to react to situations like this with direct firepower, and you can make an argument that this is the right thing to do. But was it? Would rushing the two girls have been adequate? A warning shot? A taser? In countries like Norway and the UK it would have been handled differently simply because cops in those countries don't routinely carry guns.

Shooting Bryant was, in some sense, the lowest-risk response. It was 100% guaranteed to save the girl in pink from any injury whatsoever. But would a different response have been better, even if it ran some small risk of the girl in pink suffering some (probably non-fatal) injury?

I think so.

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through April 20. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

In 2016 and again in 2018 the state of Washington put carbon tax initiatives on its ballot. Both failed. A paper from 2019 that looks at the results by precinct concludes that opposition was almost entirely explained by ideology: conservatives didn't like a carbon tax while liberals did.

This is boring and unsurprising. But naturally I like it when rigorous research confirms my beliefs, so here's a section from the study on a whole different topic:

Fifth and finally: Why do surveys overstate actual votes for a carbon tax? Using our individual survey data, we estimate that support for I-1631 in Washington is 20 percentage points lower than in other states, controlling for ideology and demographics—but find no such gap for eleven other environmental policies (e.g., the Kyoto treaty).... We interpret the Washington penalty emerging from our difference-in-differences estimator as a campaign effect: respondents exposed to Washington’s two real-world campaigns and actual vote on a carbon tax exhibit lower support than respondents considering a purely hypothetical initiative.

....Thus, while the qualitative patterns in our survey data are consistent with the actual vote in Washington—namely, that a carbon tax is more popular among liberal voters—surveys may be unreliable guides to the absolute number of votes in a referendum.

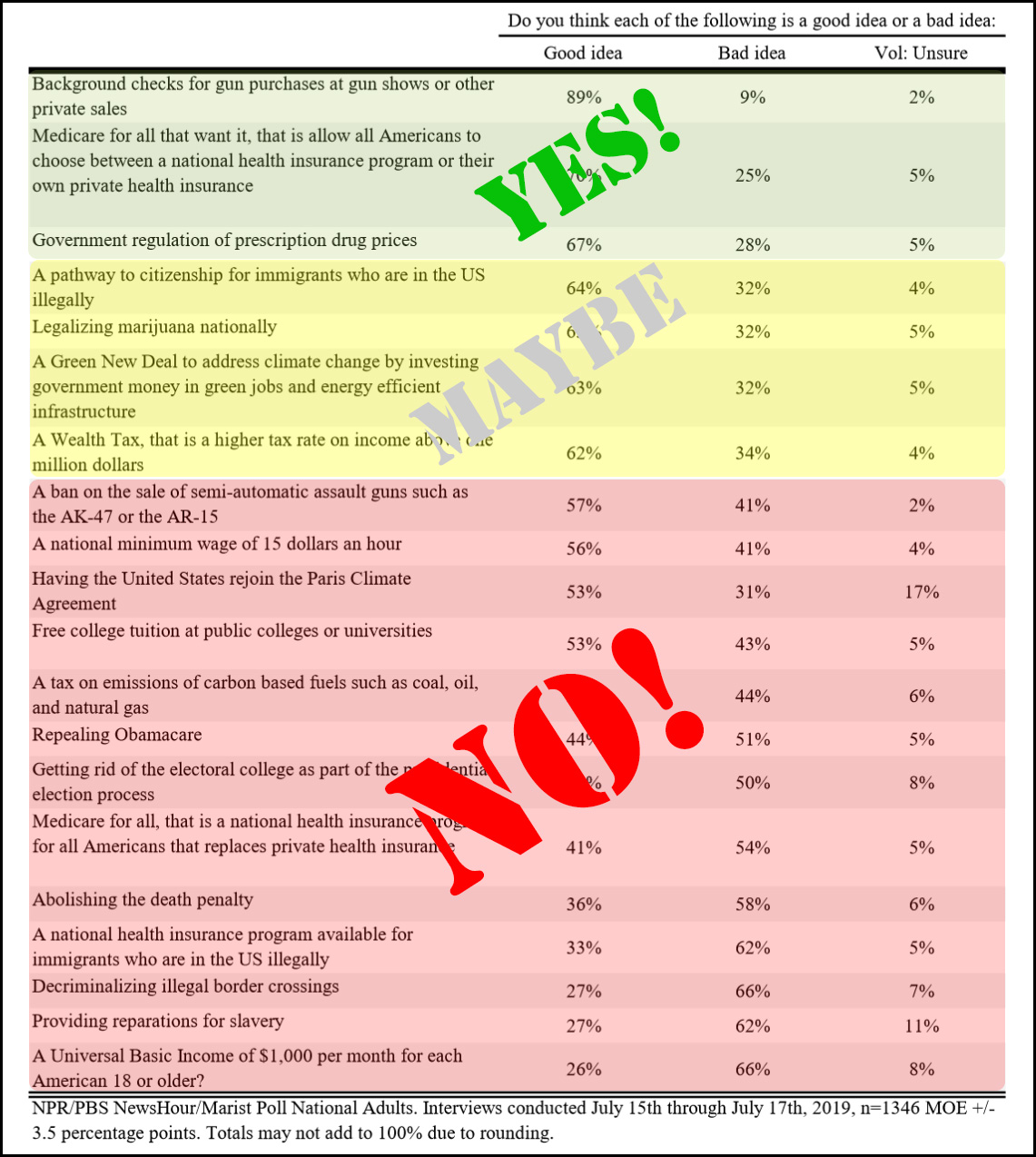

No shit. This is something that I wish I could pound into the heads of all the liberals who constantly claim that "liberal policies are popular." It's true that they are, but only in polls where people don't really give it much thought.

But the opposition gets a say too, and once something ends up on the ballot (or in Congress) and people start hearing the details of what something will cost and who it will affect and so forth, you're going to lose 10-20 points of support almost instantly. That policy that polls at 70% approval? It might squeak through. But the one that polls at 60% is a deader.

In other words, liberal policies simply aren't as popular as most liberals think. I posted this list of liberal policies a couple of years ago, and I think it deserves reposting. Read it and weep.

Following yesterday's picture of the Milky Way, some of you might be wondering just what I was doing outside of Barstow at 4 in the morning in the first place. I'm glad you asked.

On Friday morning I read a story in the Washington Post about a bunch of new National Scenic Byways designated for 2021. In particular, I read this:

California Historic Route 66 Needles to Barstow Scenic Byway, California

The western leg of the Mother Road wriggles through ghost towns, dusty outposts and the Mojave Trails National Monument, which contains the most unadulterated section of Route 66. There are a few places to stop for an Americana fix and pics, such as the Baghdad Cafe, the setting for the 1988 movie, and the “Roy’s Vacancy” sign.

I had never done this, and since Friday was a dex night I figured I should give it a go. So I took off early Saturday morning in order to get out to dark skies in time for a Milky Way photo and then drove to Needles, where I turned back and took Route 66 home.

Unfortunately, I didn't read the Post description quite carefully enough. It's accurate as far as it goes, but it fails to point out that the two things it mentions are literally the only things on that stretch of 66. There are no ghost towns and no dusty outposts, unless you count the occasional run-down house or gas station—which gets uninteresting almost instantly. Route 66 between Needles and Barstow is, basically, a hundred miles of scrub desert, and that's it.

So the trip was a bust, though I did get a few miscellaneous pictures pretty much unrelated to Route 66. That's not enough to justify 12 hours of driving, but at least it's something.

As near as I can tell, it's practically conventional wisdom that Black people nationwide will break out in an orgy of violence if Derek Chauvin isn't found guilty by a jury of his peers. This piece is typical, but you can find others like it in practically every city.

Am I the only one who finds this at least faintly racist and stereotyped all by itself? Would we make the same assumption if Chauvin's victim were Hispanic or white or Asian or Arab?

I dunno. Maybe I'm way off base here. But the automatic association of Black anger with Black violence seems like precisely the kind of thing that BLM and other anti-racist groups are trying to fight. Am I wrong about this?

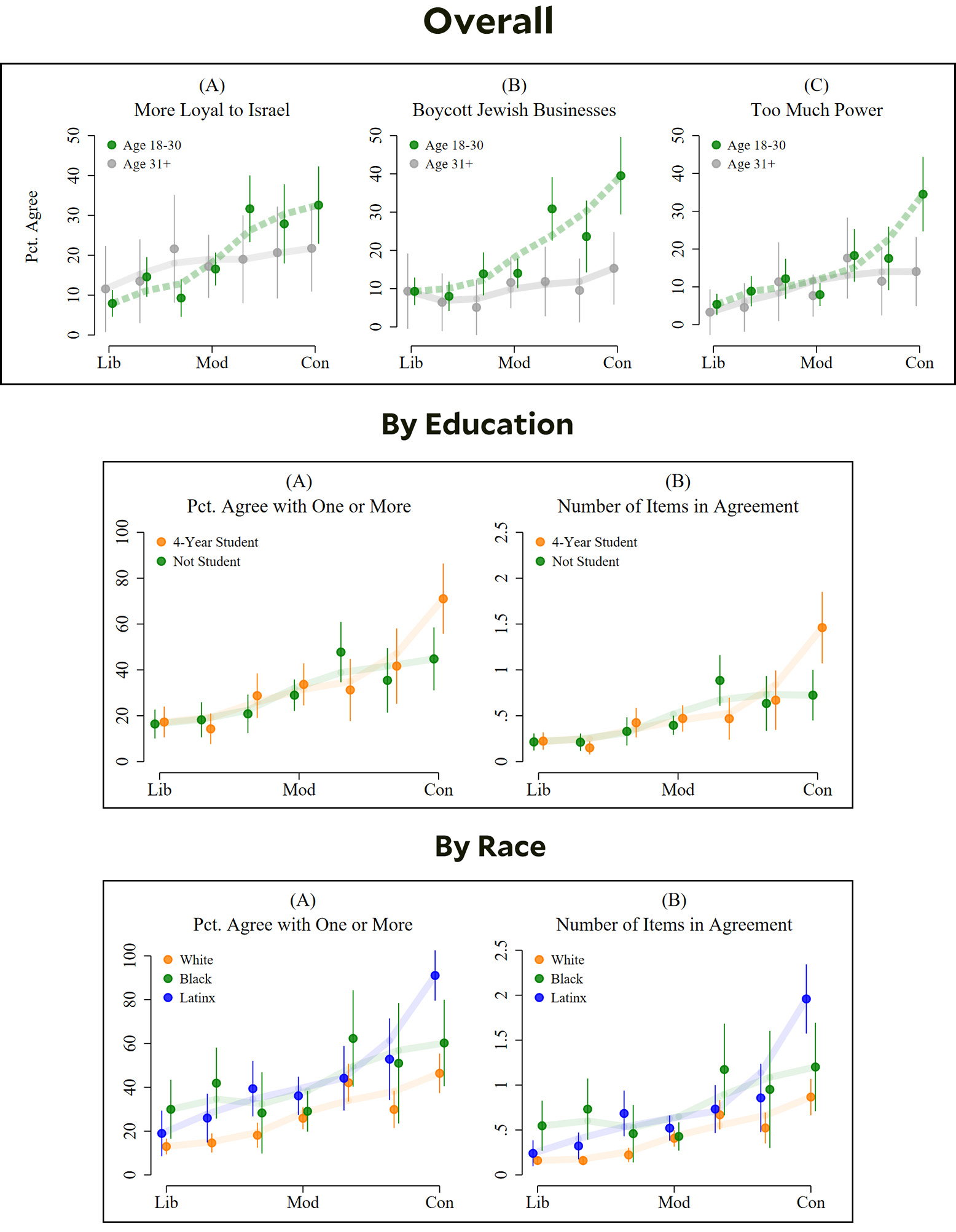

Here are some remarkable new survey findings from a pair of researchers about antisemitism in the United States. Their methodology was pretty simple: they asked people about overt antisemitic attitudes and tallied up the results.

This has always been a problematic methodology for surveying anti-Black attitudes because the questions on existing surveys have always been a little vague and hard to draw firm conclusions from. This new study solves that problem by just outright asking things like "Do Jews have too much power?" There's not much wiggle room there. Here are the results:

In every case, antisemitism rises modestly as political views become more conservative, but then skyrockets at the extreme end of conservatism. Much of this appears to be driven by age and education: highly conservative young people are about 20 points more antisemitic than older people and highly conservative college grads are about 30 points more antisemitic than highly conservative non-grads.

In addition, highly conservative Latinx respondents are massively more antisemitic than Black or white respondents. This is mysterious, though I suspect the sample size for this group is pretty small.

The authors don't really hazard a guess about what drives these results. They just present them. And given that the survey instrument was a YouGov panel, it would be wise to wait and see if they can be replicated. But if this pans out, it means that conservatives have a real problem on their hands with their young college grads.