Having written a technical preface a couple of days ago, it's now time to write a review of Brad DeLong's Slouching Towards Utopia. I'd like to keep this tolerably short, but even  as I type these words I know that's not in the cards. Don't say you weren't warned.

as I type these words I know that's not in the cards. Don't say you weren't warned.

OK then. Roughly speaking, I'd say there are two main themes in STU:

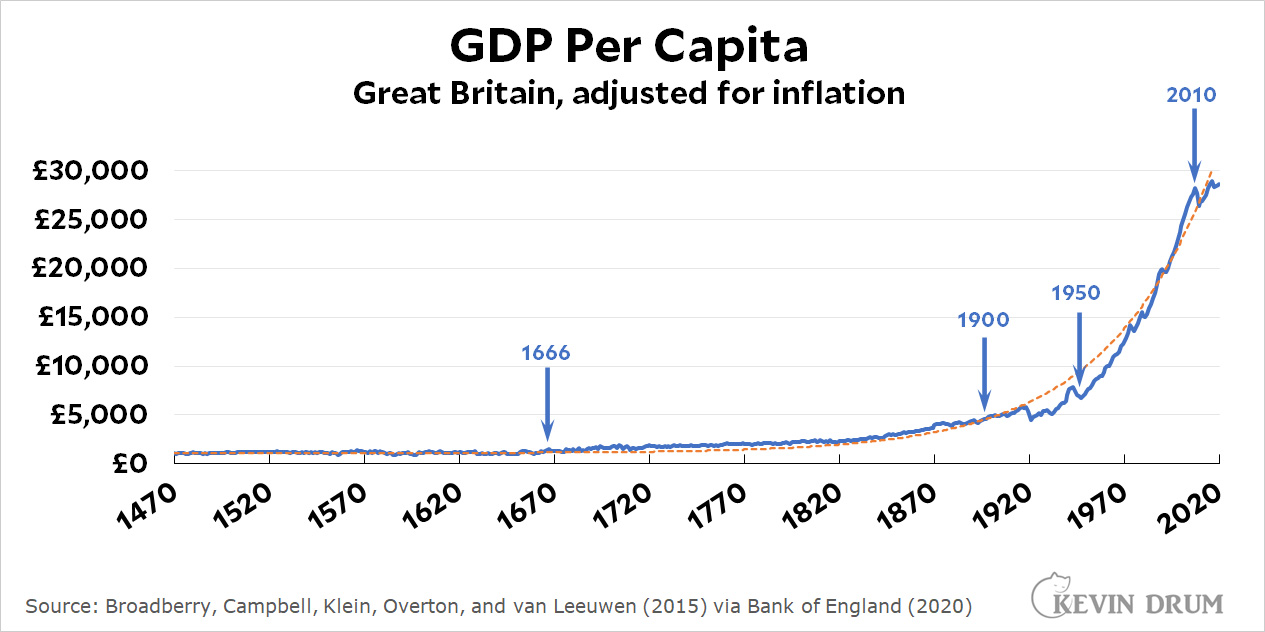

- The year 1870 is a breakpoint in human history thanks to the development of globalization, modern corporations, and industrial research labs. Because of these things, it's the first time that the world—or, more precisely, the northern half of the world—broke out of its Malthusian trap and began to provide permanently higher incomes to common workers. (I am skeptical of this for reasons I outlined at length in the preface.)

- The economic history of the "long 20th century" from 1870-2010 was primarily a contest between free-market capitalism, which produced growth but not an equitable distribution of goodies, and the welfare state, which interfered with the efficiency of the market but allowed everyone to benefit from technological progress.

First things first: purely as an economic history, this is a wonderful and engaging book. I didn't learn a lot that I didn't already know, but a large part of that is because I've been reading Brad's stuff for 20 years. Nevertheless, I enjoyed reading it again all in one place.

But I had a problem with it. I explained in the technical preface that I didn't buy the notion that 1870 was special per se. Rather, it just happened to be the point on the growth curve of the Britain-led Industrial Revolution that produced per capita GDP high enough to start trickling down to everyone.

Nor did 1870 represent a sudden outbreak of new inventions. Here's a brief list of 19th century inventions and ideas:

- High-pressure steam engine

- Steamboats

- Steam locomotives

- Canal networks

- Telegraph

- Rifle/revolver

- Electric motor/generator/dynamo

- Vulcanized rubber

- Portland cement

- Colonialism — I'm thinking here not of the necessarily limited coastal version but of the brutal extractive version that dominated the second half of the 19th century.

- Modern fractional reserve banking

- Steel-hulled steamships

- McCormick reaper

- Sewing machine

- Bessemer process

- Limited liability companies

- Safety elevator/skyscrapers

- Progress — by which I mean the idea that not only should we expect technological progress, we should actively promote it. Manifestations of this are things like patent offices, industrial labs, and research universities.

- Internal combustion engine

- Mail order catalogs

- Telephone

- Light bulb

- Public health improvements

- Automobile

- AC electricity grid

These things span the entire 19th century. Some are ordinary physical inventions (steamships, light bulbs) while others are ideas or organizational improvements (progress, capitalism). Some have specific invention dates, while others developed steadily over long periods. But nothing about this list suggests any kind of sudden surge around 1870.

Does this really matter? It does. The whole concept of 1870 being special is surprisingly central to Brad's larger thesis. His contention—and I hope I'm being fair here—is that the miraculous growth which started in 1870 opened up the doors to utopia (thus the title of the book). That is, it suddenly became possible to envision a future in which every one of us was literally awash in the products of our factories and laboratories. All we had to do was follow a simple path that was now clearly marked out for us.

But we blew it. There was World War I. Then the Great Depression. And World War II. Then the "Glorious 30 Years" of fabulous growth, but followed by the neoliberal turn in which ordinary workers were once again cannon fodder for the rich. And all along we failed to include the global south in our growth revolution. Finally, the Great Recession of 2010 exposed our financial system as a lie, and in 2016 the election of Donald Trump showed that ordinary workers were fed up and no longer believed the lie.

That sounds pretty discouraging. But what if 1870 isn't special? What if it's just another year in a long period of human progress—unprecedented progress, to be sure, but a long, continual period nonetheless? If that's the case, then there's no reason to view it as a turning point and no reason to think that human nature should change just because we all got steadily richer. In other words, we didn't blow it. We just did what h. sapiens does and always has done.

As Brad knows well, because he's written similar things frequently, we humans are just overclocked primates. We have developed a thin layer of cognition that allows us to gossip more effectively and solve differential equations on request, but that thin layer lives on top of millions of years of primate evolution. And we are still bound by it. In particular:

We are territorial.

We are patriarchal.

We are hierarchical.

We are addicted to dominance displays.

We are tribal.

So just as always, after 1870 we continued to have stupid wars. We continued to base our social structures on racism and tribalism. We continued to be seduced by charismatic (male) leaders. We continued to do stupid things just to show that we couldn't be pushed around.

This is, perhaps counterintuitively, a more optimistic view of the world than Brad's. He thinks something should have changed in 1870 and he's disappointed that it didn't happen. His entire book, but especially the last few chapters, is clouded by despondence over the events of the past century and, especially, the past decade.

I, on the other hand, think that nothing special should have happened just because we got better at inventing things. And it didn't. We just continued on our sloppy way, complete with wars and exploitation and lynchings and occasionally lunatic political parties. Still, we've made progress on all these things. Not a lot, but what do you expect in only a few hundred years?

This is why, for example, I think that our current MAGA-inflected politics is a pothole, not a roadmap for the future. We'll get over it.

As for economics in general, you all know what I think: in another 20 or 30 years we will have cheap, genuine artificial intelligence. That will be a breakpoint in human history and will make all our current arguments moot. Practically any economic disagreement you can think of simply makes no sense in a world dominated by robots and AI.

But we should keep arguing anyway. After all, I might be wrong about AI.

I'm not sure it is a pothole. Ever since Gingrich, politics has been a zero-sum war. Tangerine Palpatine kicked it up a notch. How do we get back to a society that values progress and not kicking down?

Exactly when did we value progress? And when did us apes not revel in kicking down and kissing up? Not on my lifetime.

Maga is nothing but petty bourgeois globalism. A con of a con. When the debt system goes, it's all over. State bonds will blow out, all business will collapse. Tribal ways will be all that's left.

No lies detected.

The 2016 Whitelash & 2021 March on Washington were the Cardealers Revolution. Truly, Decembers to remember...

I have been a skeptic of your AI timeline. Not the revolution that widespread AI will bring, but when we will get there. However, the recent stories of the revolution in chess engines (and the subsequent ability to use them for cheating) has changed my mind. If such a complex set of problems as chess can be overcome by machine learning so completely since the days of Big Blue, that is, in just a few years. Then development of true AI is not far off.

See, it is possible for a mind to be changed by new facts, even a 69 year old one!

What is all of this with the "global south"?

This is not a "wealthy elite" situation. 80% of the world's population lives in the Northern hemisphere. This is not a situation at all comparable to the distribution of wealth where a small minority have the majority of it.

This seems like an oblique way of saying "we did shitty things to Africa and the Americas" but at the expense of completely erasing China, India, and, really, most of Asia.

We did shitty things to China, India and, really, most of Asia too... 🙂

The "global south" is not limited to the southern hemisphere. It's usually considered to be Latin America, Africa, southern Asia (including China but not Japan), and associated islands. In other words, the more southern portion of the global land area, irrespective of the equator.

I think the post-1870 surge was essentially a political reality, not the result of technology.

Anecdotes aren't data, but I just finished an interesting book entitled, "the Judgment of Paris: the Revolutionary Decade that gave the World Impressionism," by Ross King. Although the Impressionists developed their style, reputation and controversy under Napoleon III, they didn't sell anything; Eduard Manet sold two paintings during the 1860's.

After the Franco-Prussian war, however, Paris was visited in increasing numbers by rich Americans and Russians anxious to prove they had acquired "culture" while visiting Europe. Paul Durand-Ruel, an art dealer, realized he could "sell the controversy" in fine art to these rubes, and therefore one fine day he purchased every painting Manet had in his studio, to the astonishment of Manet and everyone else, and then used his new supply to make the Impressionists famous.

Until I read this book, I hadn't realized how much the culture of the Belle Epoque had been created to be marketed to outsiders.

I think the interconnectiveness of the world beginning in 1870 is the like the emergence of the Internet: it may not show up as a cliff in the productivity statistics, but it's real.

Without the technology, you have no political reality.

Agreed, but the awareness of what the technology can do won't spread until the political climate allows it to.

Doesn't technology drive & alter the political climate?

Does Kennedy win without TV? Do BREXIT & Trump win without social media?

Here is the thing, Brexit is globalism. The point people miss. Changing econblocs is yawn.

Hitler needed radio and talkies.

I was about comment along similar lines: the aristocracy of birth and of the divine was slowly being replaced by the aristocracy of business and of secularism. This new crop needed jewels (marks of status), wealth (power), positions (levers of power), etc.

Maybe the wars could be even seen as the manifestations of this transformation, a rear action against the onslaught of the proles lead by the bourgeoisie.

Around the World in 80 Days, 1872.

In the US, the civil war ended in 1865, the 15th amendment was ratified in 1870...

The US civil war rendered everyone's navy obsolete. And changed the nature of ground warfare too.

Transcontinental railroad 1869

Capitalism is just a giant debt fraud based around technology. When the industrial revolution ended after WW1(yeah, they said 1950, but growth in real terms slowed largely after ww1 and the first large industrial consolidation happened), the bourgeois state stepped in and took Bernie Lomax making you believe he is still alive. Then when the financial crisis came in 2008, due to the bourgeois states actions, Bernie starting getting up and gyrating oddly.

Maga???? Could care less. Petty bourgeois globalism with its homoerotic mentality sickens too many people. The bigger threat is another problem of the IE, fossil fuel pollution. Something white men noticed at the dawn. The problem of yelling danger why a hedonistic orgy is going on, is hard. Now everybody globally is doing it. Thus the planet is dying with all the pollution and nonwhite overbreeding. It requires a man's socialism to reverse course. Women as livestock.

This reminds me of the rants of angry libertarian tech guys in the early days of the internet. I mean the compuserve & prodigy days. I think I heard something like this from a pony-tailed hacky sack guy at the coffee shop in 1994.

Please don't feed the racist homophobic troll. It only leaves its droppings to get attention.

Libertarian??? Try left hegelian

Kevin has probably been reading DeLong too much. Is this where he got his peculiar ideas about the "success" of neoliberalism?

The paradox of the human condition is that the masses consistently tolerate gross inequality of power and wealth, from ancient times to the present day, when there is no rational basis for it. Other primates might have hierarchies, but the top chimp doesn't get to live in a gorgeous tree house being served delicious food by obedient servants while the rest of the whoop scrapes a bare living in the stunted shrubbery.

People could collectively force change in the distribution of wealth and power any time they choose, but they rarely do it, and when they do, the old inequalities soon re-emerge. It's a puzzlement.

Don’t really think AI is anything but a weapon to oppress and humiliate. What is the reason for some optimism? The internet is a catastrophe for humanity. The Chinese have weaponized it. The Russians have as well. Before too long we’ll all regret having made comments on this site.

Will AI make stuff we need? Will it provide food, fuel, and shelter? Will it build things? Will it deliver medicine or change our adult diapers? Or will it just entertain us? Or will it know what gets me off and feed me that content?

Silly. Looking back 60 years, what is really different? Stuff is done faster, not really better.

Your daily downer from Justin. You won't find any sunshine from him!

Hope for the best, prepare for the worst.

I’ve worked in manufacturing plants for going on 35 years. Little has changed.

> Silly. Looking back 60 years, what is really different? Stuff is done faster, not really better.

Yeah ... remember those great '60's iPhones?

The gas station paper maps were way better at reciting directions while you drove through a strange city. And so convenient, especially when you didn't have the right one.

And gas was so much cheaper then, which is a good thing considering my Ford Mustang got about 15 mpg. Maybe. The pollution control devices on it were a lot simpler, though - merely the large volume of empty air surrounding the vehicle - very low maintenance!

If nothing were changed from 1955, then we never would have seen either Bernie or Trump get any traction among their primary electorate in 2015-16.

The whole ethos of both #MAGA & #ourrLOVEution is to make America pre-Elvis again, just in slightly different ways.

& now I see this playing out in the gubernatorial race here in Oregon, where the GQP nominee Christina Drazen wants to make Oregon 1858* again, a new frontier where restrictive covenants & tight controls on the border can make all the peskiness over the Negro problem go away by ensuring the Beaver State can achieve its original goal as Whitekanda. (& this time, most of the Indigenous population is already swept out.)

*Betsy Johnston's Oregon 1985 dream isn't much better, wanting to restore Andy Ngo & Joey Bishop's white power RAHOWA scheme to its pristine state of being, before the white punks on dope ended up bankrupting the movement by enabling the frivolous lawsuit of an Aethiopaean child whose father they killed in 1988. Jesus, that was only thirty four years ago, a week after George H.W. was elected to Reagan's third term.

Here is a quick downer of my own. Don't all of the optimistic scenarios, like the book Kevin is writing about, think that economic growth can continue forever? But that requires exponential growth.

For example, if you had 1000 of anything (people, money, resources) and it grew at 3% a year, after 50 years, you would have more than 4000 of that thing. And after another 50 years, you would have more than 16,000....

I know resources are NOT growing nearly that fast. Space on this planet is not growing at all. So my question is, WHEN must growth stop? And how does it stop.

256 doubling is all it takes to go from a single baryon (proton or neutron) to all of the matter in the visible universe. In your example, 3% growth is doubling in 25 years; that can only continue for 6,400 years before it consumes the entire universe. Not very long at all.

Don't confuse economic growth with growth is physical stuff. They are not the same thing.

Yes, we cannot have continuing growth of physical stuff, because there are limits to how much physical stuff there is. But those limits do not apply to things like money or value, because these things are conceptual rather than physical.

Consider Nasrudin's comment above about phones. A 2020 mobile phone contains *less* physical stuff than a 1960 desk phone, yet is so much more capable (and arguably valuable) that there is no good way even to compare the two. Similarly, a more efficient automobile is a better (more valuable) automobile, even though it uses *less* fuel to do the same work.

Brexit is how globalists play games with the peasants. Not only was it not out dated and materially nationalism, it was just switching eurozone to amerozone. If the Scotts and Irish didn't exist, it would have had close to 90% support in England. Like a old 90 year old trading living with your younger siblings with your children.

C'mon man. You're chasing a semantic point that you know is just a broad marker for the start of the Industrial Revolution.

See what I did there?

I haven't read his book, but if I were to guess, wealth generated by labor is a core principle. If wealth is generated by machines, how do laborers earn a living?

For years you has expressed disbelief in the structural change of the economy, driven by the comfort of inertia. And yet, blue collar voters shifted to Trump by the allure of false concerns (fake populism) expressed by conservative voices.

What good is our economy if it is driven by capital for capital's sake? Peak Capitalism isn't free markets; it's the death of labor and the insistence that the problem of the worker is that s/he doesn't work hard enough.

You ARE wrong about AI. After all, 10 years ago you predicted it 20 to 30 years off. Shouldn't it be 10 to 20 years now? It is eternally 20 years off.

Ooh, do you think we'll get it before or after nuclear fusion power ? Or before or after genuinely modular nuclear fission units ?

Like Iran's nukes are always just a few months away.

"what I think: in another 20 or 30 years we will have cheap, genuine artificial intelligence" and that will really give us fully driverless vehicles, right ? And Musk will become even richer.

In your 19th century "inventions", you missed commercial refrigeration. Sure, the domestic household refrigerator was first produced in 1913 by an American, but:

"Newspaper proprietor James Harrison, of Geelong in Victoria, was among the pioneers of refrigeration. He created Australia’s first vapour-compression refrigeration system using ether. In 1851 he developed his ice-making machine. In 1854 it began operation commercially, a patent was granted in 1855 and he was commissioned to build a refrigeration system for the Glasgow & Co. brewery in Bendigo. His system was soon in use for meatpacking houses and breweries."

Did this kickstart Australia as a lamb exporter providing more meat for the average English worker?

Nah, Victoria just gave its gold to Threadneedle St instead. That's what you get for being a small domain in a big empire.

'We are territorial.

We are patriarchal.

We are hierarchical.

We are addicted to dominance displays.

We are tribal.

''

As long as we recognize these as less than desired traits and work at improving ourselves, we are making progress. We haven't "blown it." I venture to say that on the whole we are less all these things than we were a century ago (despite the occasional paroxysms such as those exhibited by the MAGA world). That is progress.

Sez you. _Some_ people are patriarchal/hierarchical/addicted to dominance. And they are a minority, thank goodness, though admittedly they are the major source of the world's woes.

I think cheap - almost free - energy is the only thing that can save - or ultimately destroy - our sorry h. sapien asses.

Your "Five We's" manifest failures of education: failures that were once survivable, but that, since the late Eighteenth (NB. not Nineteenth) Century have been gradually becoming less and less survivable, to the point now here, if they were not to be overcome pretty much immediately, they will end us in a very short further time.

As far as the DeLong-Drum debate I am on Kevin's side in matters of human failings. Just look at Werner Heisenberg, a genius in the field of scientific/technical progress and at the same time a Nazi sympathizer if not an outright Nazi. Or Ford, the man of industrial production, also tainted by Nazi association.

As far as AI: If it is as consequential as advertised (a big if--a first in tech history, every invention relating to the internet has been overhyped so far) it will be different from anything anybody imagines. We can't know now if it will be beneficial for humankind or not.

Lol, Ford was a con man and some Jewish ancestry. It's where the joke "International Ford" came from.

I've read a couple of reivews of De Long's latest; as any reasonable person would expect, the reviewers are _not_ impressed with his thesis.

There's always a problem picking a year. I recently read a book about New World archaeology and history that chose 1491 as a pivotal year, though the conquistadors wouldn't arrive for another 20 years or so. There was a great book about 1959, the year that gave us the birth control pill, integrated circuits, the Civil Rights movement, and major artistic advances.

1870 was when science and technology could no longer advance using only our senses and familiar physical intuitions One needed mathematics, specialized instruments and a lot of non-obvious theory. I agree with our host here that this was part of a continuum. Steam power, the telegraph and improved machining techniques defined the 19th century. To move on require understanding electromagnetic radiation, chemical bonding, post-Euclidean geometric curves, differential equations and a host of other invisibles and intangibles.

The book "1491" uses that year as a metaphorical stand in for European contact, not as a specific inflection point.

I'd choose the end of the last great ice age, as opposed to 1870, as the inflection point. For our species, the period since then is proportionately equivalent to the last 6 months for a 13-1/2 year old. In other words, our species is just getting used to childhood's end and a nascent adolescence.

Metaphorically speaking, our hunter-gatherer period represents the 13 years of childhood in which we were decidedly egalitarian, and decidedly not hierarchical. That's the opinion of Christopher Boehm who is someone that should know. Ref: Hierarchy in the Forest (2001)

For someone that thinks they're not tribal, take a DNA test. You might be right if it comes back frog or scorpion. You're wrong if it comes back Homo sapiens. The only question is who's part of and not part of one's tribe.

There's a principle that will tell you who's in and out. For those that are in your tribe, you'll use the "do unto others as you would have others do unto you" principle. You'll otherwise use the "do as I say and not as I do" principle. My opinion is that our species will get over this early adolescence phase when we collectively figure out we're all part of the same tribe.

As long as the American people retain the power to vote the MAGA politicians out of office, I am reasonably optimistic that we will get to a better place politically a few decades from now. But this is the first time since the American Civil War that we've faced a serious challenge to democracy in America, and I don't think we can be sure how that will play our, or what the path back to democracy is if we lose it. My largest campaign contributions this year have been to Adrian Fontes and Cisco Aguilar (candidates for Secretary of State in Arizona and Nevada, respectively) because it's clear that their opponents don't believe in honoring election results they don't like.

Another excellent piece. Thank you.

Pingback: Links 9/28/22 | Mike the Mad Biologist