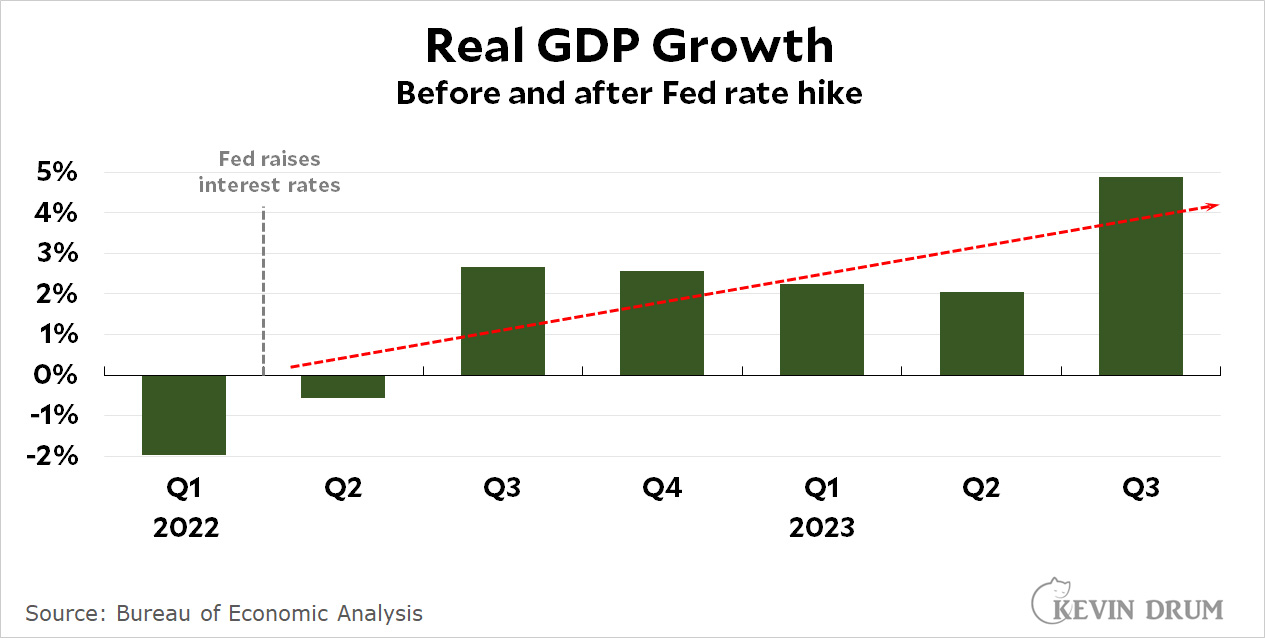

You all know that I'm a bug about the delayed effects of Fed interest rate hikes. Here's a simple chart that shows why:

Fed interest rate hikes don't directly affect inflation. They produce higher long-term rates which in turn slow down the economy. That's what reduces inflation.

Fed interest rate hikes don't directly affect inflation. They produce higher long-term rates which in turn slow down the economy. That's what reduces inflation.

Long-term rates have indeed gone up since the Fed first started raising rates, but that's only the first step. So far the economy hasn't responded. Just the opposite, in fact: it's gone from strength to strength. If the Fed's hikes have had any effect at all yet, this would certainly be a very strange one.

The more likely explanation is that we're still waiting for the Fed's rate hikes to produce any economic change. It normally takes at least a year for Fed action to affect the economy, but it can take longer. We're now at the 18-month mark, and it's hard to believe that it will take much longer.

This is why I think we're in for a recession. Hopefully it will be a light one, but there's no special reason to think so. I'm not worried about either Joe Biden's age or alleged unpopularity, but I'm definitely worried about a recession. The party in power never wins an election if there's a recession in the first half of an election year. Just ask Jimmy Carter, John McCain, and Donald Trump.

No, the more likely explanation is that the Fed's prime rate is more decoupled from measures of inflation than it has been previously. The economy of today is fundamentally different from the economy of even 30 years ago in several important ways (in order of my intuitive importance):

1) Corporate/market consolidation. Monopolies and oligopolies rule nearly every type of market in the modern (US) economy.

2) Housing supply is very out of whack with demand, and housing is the single biggest ticket in price calculations for cost of living and inflation.

3) Globalization and the internet age/ecommerce

4) Vertical integration (kind of a sub-item of number 1, but it's still an issue)

All of these things provide for GDP and price increases that are more insulated from interest rates than the economy of the past.

Beyond all of that, given that the Fed's rate increases are immediate, I would remain confused with the constant insistence that they haven't had any impact yet except for the fact that insisting such a thing supports your narrative. It's simple fact that the Fed's rate increases take effect immediately, and are cumulative (as more debt rolls over or is initiated). But it has an immediate impact on things that regular households interact with every day: credit card rates and home mortgage rates (obviously for new mortgages, refinances, or HELOCs only - but that's still a non-negligible impact).

For fuck's sake. These posts are dead horses that I'm tired of beating.

This here is overstated: "1) Corporate/market consolidation. Monopolies and oligopolies rule nearly every type of market in the modern (US) economy." Although agreed there is increasing messiness for the Fed for Prime Rate feed through - this is not entirely new, it is one of the reasons why Fed and other Central Banks in post financial crisis adopted quantatitive easing.

However absolutely agree: "It's simple fact that the Fed's rate increases take effect immediately, and are cumulative (as more debt rolls over or is initiated). But it has an immediate impact on things that regular households interact with every day: credit card rates and home mortgage rates (obviously for new mortgages, refinances, or HELOCs only - but that's still a non-negligible impact)."

The bizarro world idea that Drum is presenting with the bizarre distortion that Fed rates impact when there is impact on long-term rates is just.... inexplicable.

One should also add in that small businesses in particular (but also larger ones depending on market) typically are directly exposed to Short Term rate rises from both consumer like channels (their credit cards which often are used as working capital) and proper business credit at floating rates, working capital revolvers as well as short term term-loans (I suppose in USA this is more fixed then elsewhere).

Krugman's working hypothesis (as I recall reading some months ago, hopefully not inadvertantly distoring) that the impact of Fed rate rises has been to tamp down what otherwise would be higher inflationary pressure as IRA and other effects feed through seems entirely plausible.

Definitely agree on Krugman's hypothesis, although unfortunately I don't get to read his stuff anymore because of the paywall. But the secondhand discussion gives the gist.

Perhaps the corporate consolidation angle is overstated (it's not like we're living in an era of just a few megacorps, obviously), but I don't think there's zero impact there. Interest rates just impact larger companies less than they do smaller ones, and we have many more companies with sector dominance than we used to as compared to the last time inflation was over 6% (1990!!!). 1990 was also the last time, aside from a short period around 1999-2000, the Fed's rates were this high. In addition to the consolidation factor, corporations also have way, WAY more cash on hand than they used to: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/QFRTCASHINFUSNO. I don't think that consolidation (which I don't see as entirely unrelated to stockpiles of cash, given that consolidation is done to kill competition, which de-incentivizes a need to invest and innovate, and make more profit) is a non-negligible factor in a hypothesis for why This Time Is Different when it comes to interest rates vs. inflation.

Agreed also on the quantitative easing angle vs. prime rate.

It also just sucks that Fed policy is the only hammer we have for a problem that's more like a complex machine than it is like a nail.

I certainly agree that corporate concetration is a real effect, I perhaps over-read your comment but felt concentration is not broad in all segments of the economy (globally, or USA) but it is a genuine concern from economic policy PoV (in this area and broadly).

You make quite valid points on the effect in re large corporations, weights and influence which in interest rate terms probalby is indeed overweight.

I'll go ahead and note, as others will undoubtedly see, that you've conveniently started your chart at the first quarter of 2022, which was a weak quarter, making the moderate growth through Q2 2023 look great. But those quarters weren't that great. Wouldn't your readers be interested to know that real GDP growth from Q4 2020 through Q4 2021 was bopping along at rates averaging better than 5%?

Also, you continue to utterly ignore the fact that the rate hike plan for 2022 was revealed by Jay Powell in December 2021. This was well reported, and it is plausible that it had an almost immediate dampening effect on the economy. It seems less plausible to me that the higher-interest policy announced in 2021 is still waiting to exert any drag on growth now, 21 months later, as we have just seen the best quarter in nearly two years.

I have a low interest mortgage which I refinanced 2 years ago. I’m set. Not gonna move. I have a 6.5 year old car which is paid off and I’m not going to buy a new one since I don’t drive much anyway. If I’m forced to buy a car because of an accident I can afford to pay cash for a cheap one. Interest rates don’t affect consumers like me. Who do they affect?

Business lending. Spare me the concern for idiots in venture capital. None of those companies are worth saving. So if you don’t need to finance a car or a house these rate don’t matter. Crappy business models are going to fail. Good. Does any of this cause a recession? I don’t know… probably not.

Interest rates don’t affect consumers like me. Who do they affect?

People who would like to sell their homes and move (or purchase their first home). This segment of the population tends to have an oversized impact on wider demand and employment because of the sheer size of the transactions involved, and the various spillover purchases. Housing is nearly a fifth of US GDP.

No, such a description doesn't apply to everyone, but neither does the rosy picture you paint of your own situation (locked in low mortgage, no need to move). Also, even people who don't need to move are probably being impacted, in that HELOCs and home equity loans have traditionally been a source of funds for purchases of things like cars, furniture, appliances and remodels. And interest rates on car loans are the highest they've been since 2007.

I think it's possible Kevin's wrong and we'll dodge the bullet of recession for a long while yet: the average postwar expansion in the US has been something like 5.5 years, I think, and we're only a bit over three years in at this juncture.

But if we do avoid recession, in my view it will most likely be because interest rates begin to significantly drift downwards. If they don't, Kevin is probably right a recession will arrive before too long. And I'll note headline unemployment is up nearly a half point since this past spring.

Youve made the case for why this could have a big impact.

You tell us that many people could say that they wont let higher interest rates affect them because they can buy fewer houses, cars and housing remodels.....and you also announce that lots of businesses might fail.

So you tell us that you will help slow the economy and reduce the need for jobs and production in several industries plus you can see that other industries may also be affected. This is exactly how recessions happen. Youve told us that the rates affect your decisions and will directly affect people in various industries like home building and repair, car manufacturer and selling, finance, etc...

Yes - useful conversion of a trolling into illustrative of how Central Bank rate rises effect the economy, immediately and over time.

One should clarify however that on the business side the immediate effects will be in the cost of capital - both short-term working capital (what businesses use to smooth lumpy payment cycles so they can pay salaries, suppliers etc) and investment capital. With both those becoming more expensive, businesses pull back on plans, so business spendin

Most people tend to focus on either just consumers (although I suppose sensible at some level in the consumer heavy American economy) or bankruptcies - whereas the rising cost of working capital itself is analagous to rising short-term financing costs for consumers for purchases, particularly "non-durables"

One can see by the way an impact (sadly not a desired one) in the cancellations of off-shore wind investments that were contracted and priced in the ultra-low interest rate environment but whose off-take pricing no longer make sense (the Danes recent cancellations in USA, which USA should address with gov policy really).

Personal anectdote is not data.

Of course you are trolling as usual, but it is worth noting the bizarre red herring of venture capital as if that were a response to general business credit (or even in any way relevant).

Mr. Drum wrote: Long-term rates have indeed gone up since the Fed first started raising rates, but that's only the first step. So far the economy hasn't responded. Just the opposite, in fact: it's gone from strength to strength.

The economy hasn’t responded because interest rates don’t have the economic impact they once did. But I’m going to predict there will be a recession in 2025. Trump will wreck the economy when he starts arresting his political enemies.

No..... you are misunderstanding.

It is not "interest rates don't have the economic impact they once did"

It is Central Bank changes to the base Reference Rate do not have the same speed of impact they once did for many reasons.

That is not the same as interest rates.

“The more likely explanation is that we're still waiting for the Fed's rate hikes to produce any economic change.“

This is so ridiculous it’s hard to fathom you could possibly believe this. In fact, I know you don’t believe it, because you keep posting about how the economy is getting weaker.

You’ve been predicting an imminent recession since summer of ‘22. At some point, you have to take the L.

Unemployment is higher today than it was in the spring/summer.

Its worth reflecting on the great recession and how we were 3-6 months into the recession before we even knew it. During the first several months of the recession, many people were openly dismissive and mocking the idea of a recession and anyone who brought it up, even when we were actually in a recession at the time.

But Kevin was predicting a recession would begin by Q1 2023! Two recessions, in fact!

https://jabberwocking.com/two-recessions-are-barreling-toward-us-next-year/

I’m not saying there will never be a recession ever again. My point is that you can’t take credit when one finally arrives if you’ve been predicting one for years on end.

Indeed quite fair point - along with his ever lengthening "transitory" value.

Rather than admit, as Krugman did, he misjudged (nothing shameful in that, given the complexity of data).

However Drum has dug himself every deeper while going silent on points.

A disappointment as Drum is normally quite the straight player but he has become bizarrely unmoored on this particular subject.

He said H1 2023, not Q1. Either way we only have prelim data for Q3.....so its inaccurate to say hes been predicting it for years. At best you can say he is off by a few months at this point. But i get it, its the internet so HYPERBOLE!

You’re right, my mistake. I’m fairly certain he had called for a recession by March ‘23 in other posts, but the one I linked to said first half of 2023.

See what I did there? It’s called “acknowledging a mistake.” Kevin should try it!

While reelection after a recession in the first quarter is almost certainly an uphill climb, a sample size of three (Jimmy Carter, John McCain, and Donald Trump) is a bit small to draw conclusions.

This is simply wrong, wrong, wrong (perhaps explaining why you are so consistently wrong headed on the subject): "They produce higher long-term rates which in turn slow down the economy."

NO. Wrong.

Central Banks effect interest rates - when usin the reference rates mechanism - effect first SHORT TERM rates. There is a feed through mechanism that eventually effects all rates, but the most immediate effect is Short Term.

The moment a Central Bank raises its reference rate, mechanically via funding mechanisms to banks (and other authorised intermediaries which may be non-bank FIs) and contracts that are benchmarked on such rate (or derived rates).

Thus immediately floating rates in short-term consumer credit as well as business credit climb, which clearly effects their spending power. IMMEDIATELY. Rolling over fixed rates begin to feed through the rest of the system more gradually as indeed longer term rates and the yield curve are generally benchmarking on a risk premium over a short-term rate (which one depends on contract and market practice).

The economic impact of the rise of short term rates of course is real, it can be quite substantial depending on how credit is structured in a market (certainly in consumer credit this is typically short and fast - although USA has a unique mortgage market that insulates its consumer home lending).

It most certainly is not uniquely nor solely about Long Term rates... that is utterly wrong.

Central Banks particularly since the 2008 financial crisis have used direct market interventions in buying Bonds (sovereign and high rated corporate) [Quantitative Easing] to directly manipulate long-term tenors largely because their reference rate mechanisms were not impacting as desired long-term rates.

Frankly Drum you really have a poor, very poor grasp of these subjects (interest rates, financial mechanics, inflation), incomplete and highly biaised, you really are doing yourself no credit.

So to summarize....

- Short term rates are impacted first. This has an impact immidiately.

-Long term rates change more slowly. This has an impact too, but comes later.

-You are very super smart and others are very super dumb.

‐------

Other than the name calling, this doesnt really contradict the point of the article. But I think the 3rd point was really the purpose of the post.

Well no, although I see that thin skinned Lefty knee jerking and whinging on is inevitable.

The fundamental point is Drum is wrong and badly mischaracterising Central Bank rate intervention impacts - he ignores short-term, consistently mischaracterises reference rate impact (via it would appear an important misunderstanding in a black-and-white on/off understanding of the otherwise true observation that full effect of a rate rise takes time to fully feed through, mischaracterised by Drum as "not having effect yet")

Multiple channel effects and immediate plus ongoing impacts is utterly different than what he writes - and of course his quoted assertion is utterly wrong. Actual fucking quote mate, actual fucking quote.

(what "others" has to do with this rather escapes)

And for more useful and Lefty Kosher input, Krugman (who is I shall say regardless of politics an excellent economist and generally clear eyed economic observer, as good as we can be as humans)

Teasing - a good article.

"The Fed and other central banks essentially control short-term interest rates and have increased them a lot in their fight against inflation. For a while, however, bond markets were basically betting that these rate hikes would be, well, transitory and that short-term rates would soon come way back down. As a result, long-term rates significantly lagged short-term rates, creating the famous inverted yield curve that many see as a sign of impending recession."

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/29/opinion/natural-interest-rate-higher.html

Why politics aside? Outside of his failure to predict the inflation in the first place, I rarely see a Krugman essay that is not an unflinchingly honest assessment with accurate predictions. He was right about W, right about Trump, right about Paul Ryan, the list goes on.

Why politics aside? Because Krugman's non-economic discussions are not of the same quality, that's why. As political prognasticator he is rather rubbish. But then he is an economist - and a very good one, I learned my macro from his texts in my day.

One area of expertise does not translate to general expertise.

I think I'm less up in arms than the rest of the comments section about your record on this - what frustrates me is you (or anyone) making unfalsifiable predictions. Being wrong happens to everyone, but being unwilling to be wrong is a massive red flag.

I see that in this post you've sort of weakly gestured at remedying this, but you stop juuuuust short:

> It normally takes at least a year for Fed action to affect the economy, but it can take longer. We're now at the 18-month mark, and it's hard to believe that it will take much longer.

What exactly is "much" longer? At what date would you be comfortable saying "ehh I guess I was wrong about a recession coming"?

This is wrong although it is cthe haracter of what Drum's misunerstanding is: "It normally takes at least a year for Fed action to affect the economy..."

The actual observation not lensed through Drum's misunderstanding is that there can be significant lag time for *the full effect* of a Central Bank reference rate rise to be achieved. That is not the same thing as "takes a year to effect the economy" - this is wrong, wrong, wrong and Drum transmitting this is really regrettable.

Effects occur immediately via short-term rates (this in reference to referrence-rate rises) which immediately begin to impact the short-term debt (less-than-one-year maturities, notably and especially variable rate) component of consumer and business spending. This is not trivial although the scope of impact rather depends on the debt structure of an economy, different markets will make this faster or slower depending on how much Fixed versus Variable and ST versus MT versus LT debt is out there.

What takes longer is for short-term to ladder up into medium and longer terms, which is typically due to the structure of funding contracts that resets on contracts or refinancings do not occur all at once (and particularly on the upwards side where evidently the interest in the market becomes not to refinance but to sit on whatever lower rates one has achieved earlier, for as long as possible).

Krugman is rather more useful in this subject

Example his note on interest rates from one month ago

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/10/opinion/us-budget-deficit-interest-rates.html

"There are other possible explanations for rising rates, ranging from simple supply and demand — the government is selling a lot of debt right now, and the Fed is no longer buying it — to investor psychology. But in any case, there’s no clear case that rising rates will hurt the economy in the short run.

There are, however, longer-run concerns. One is that higher borrowing costs may make federal debt less sustainable. I still don’t think we’re facing a fiscal crisis any time soon — and neither do the markets. If investors were really worried about U.S. solvency, they would probably expect higher inflation as the federal government turns to the printing press to pay some of its bills. But we can infer market expectations of inflation by looking at the break-even rate, the spread between bonds that are protected against inflation and ordinary bonds; as the chart above shows, expected inflation has remained stable and doesn’t account for any of the interest rate spike.

But even if there’s no immediate crisis, high interest rates will almost surely crowd out private investment, hurting our long-term prospects. I’m especially concerned about the effects of high rates on investments in renewable energy, which are of existential importance.

So it would really be nice to get interest rates down again. Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve can’t just reverse its policy of raising rates to limit inflation. While the inflation news has been extremely encouraging, the U.S. economy seems to be running quite hot, and cutting rates could still cause it to overheat, sending inflation higher again.

To make room for lower interest rates, then, we would need to take some heat out of the economy in another way — most obviously by reducing the budget deficit, which is very high for an economy close to full employment."

Precisely--we have to get rid of the Trump tax cuts.

Yes, that would likely help.

But then you lot need to focus on less Purity Pony politics and more broad tent in order to build a signficant enough majority across all major electoral geographies.

I think you're wrong about this and NGDP growth is a better metric of the stance of monetary policy than nominal interest rates. I also think you're wrong about the long and variable lag; changes in NGDP growth rates have near-term impacts via changes in expectations.

However, how would we know who is right here? You have been predicting a recession for more than a year and you accurately mention we're circa 18 months since rate hikes started (and counting). If we don't see a recession by end of Q4 of this year will this prompt a revisit of your view? What about 24Q1 or Q2 (basically an extra nine months on top of the 18 we've observed to date)?

If you believe this, then you're really just ignoring the "variable" part of the lags Friedman described. Are we in the pick-and-choose part of Econ 101?

We have the Fed unwinding the quantitative easing and raising rates. The federal gov't. stimulus during the pandemic helped to support the economy during Covid and gave people a reserve to draw on. And we have the infrastructure act, etc., putting money into the economy.

Inflation was mainly transitory and is finally falling. Will prices go back down--no, or not by much outside of food and energy. Supply chains are still fragile, e.g. now apparently there are shortages in milk cartons (4 and 8 oz) causing problems. Also, markets are not that dynamic--companies pushed up prices because they could, and competitors went along. 'There's little excess capacity where one company would lower prices to capture market share--and investors want their money.

We needed interest rates to go up a bit to help burst some bubbles (crypto???), say 2%. To really start to contract things, you'd need to get to 4% or higher--and the effects will be delayed--so not 18 months. Increases in productivity and worker shortages is keeping things going without large increases in unemployment--for now.

Yes I dare say if you predict a recession for 18 straight months you will eventually get one. You're predictions will be garbage, but a perfect stopped clock metaphor.

But you know what will get us a recession? Next week's shutdown.

I have stated this before but it bears repeating

The wealth transfer from boomer to millenials and genX-ers is transformative

Both Forbes and the NYT have had recent articles (behind paywalls) that estimate this wealth "value" at #88T over time.

Thats a LOT of cushion for our offspring and its already underway

I am a boomer myself. I out right own my home and 2 cars. I have money in the bank PLUS insurance policies. My final expenses are already paid for, and my will is in place. I have NO credit card debt. That last item has been a mantra of mine for a decade. I have ONE credit card with a very high limit and low interest. I use it but pay the balance before the interest is tacked on.

I have tried to pass this type of thought process on the my kids. When they were in their 20s and 30s they did not listen. Now that the oldest is in her 40s she is "coming around" and is now credit card debt free. Next she works on paying off her mortgage early

The boomers I know are pretty much in the same boat.

Any recession predictions have to take this wealth transfer into consideration. IMHO