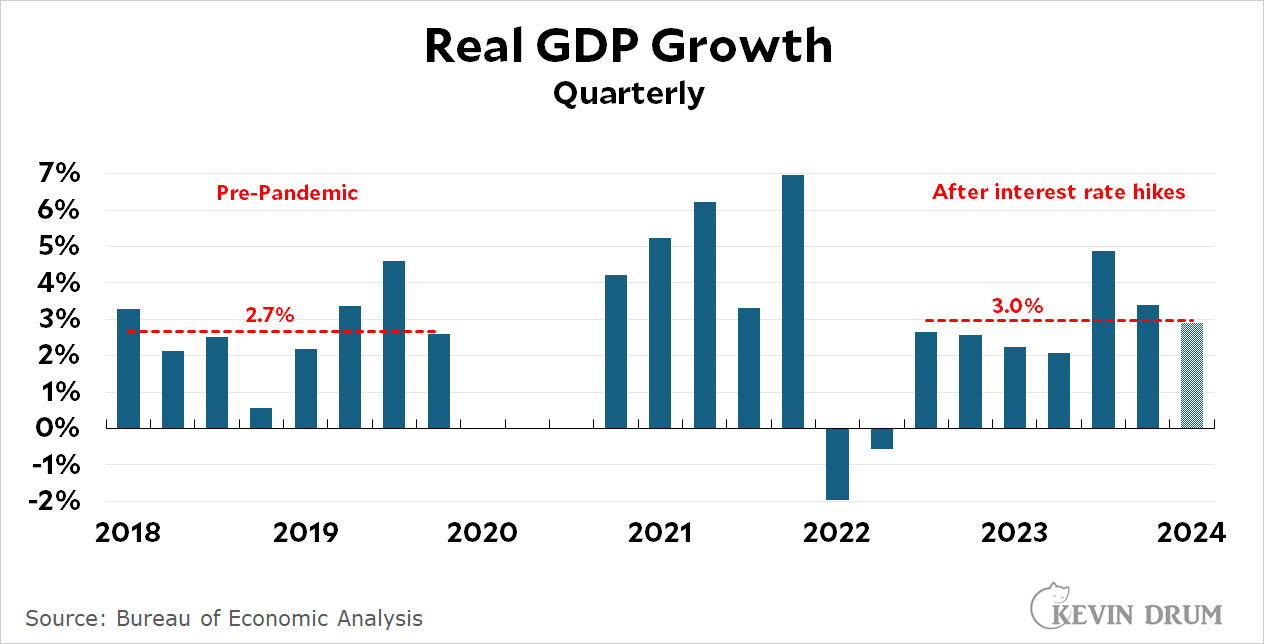

As you know, I've spent a long time arguing that the Fed's interest rate hikes aren't responsible for lower inflation. This is because inflation started to ebb within a few months of the hikes, and that's way too fast. It takes a year or two for interest rate changes to affect inflation.

Well, it's been a couple of years now, so where does that leave me? Still puzzled. You see, interest rates don't affect inflation magically. They slow down the economy by making loans more expensive, and a slower economy then brings down inflation. But that never happened. The economy never slowed down:

Average GDP growth since the interest rate hikes began has been about 3.0%. That's more than it was before the pandemic, which was a pretty strong growth era itself.

Average GDP growth since the interest rate hikes began has been about 3.0%. That's more than it was before the pandemic, which was a pretty strong growth era itself.

So what happened? This was well after stimulus spending had mostly dried up and wasn't affecting anything. So how is it that a large and sharp increase in interest rates didn't slow down the economy? Does anyone know?

I have a potentially stupid question to ask about this. I mentioned a few months ago that the Fed no longer controls interest rates via open market operations—that is, by buying and selling treasury bonds on the open market. Instead, it's mostly switched to the much easier method of changing the rate it pays banks for the reserves they keep at the Fed. If the Fed is paying 5.25%, no bank will loan out money for less, so interest rates automatically go up.

But is it possible that high interest rates have a different effect depending on how they're created? In other words, maybe higher interest rates without any open market operations behind them have an attenuated effect on the economy.

That sounds kind of stupid, but there's got to be something going on. More prosaically, maybe the fed hikes were just too small to have much of an effect. It was only a year ago that real interest rates went above zero, and even now real rates are only about 2%. In the past it's taken real rates of around 4% to touch off a recession.

Either way, it's hard to believe that no one really knows what's going on. How is it that the Fed hiked rates and produced not a soft landing, but no landing at all?

An argument has been going on for years between Robert Farley (and supporters) on the one hand, and John Quiggin on the other, about whether or not warships have become obsolete (Quiggin argues they have). A comment on the latest round read "The core problem with any kind of military experts is that they chose such a career, managed to stick to it and found someone who pays them for that job on the long term. Those are rather bad preconditions for doing objective, or frankly any kind of good work."

I found that very droll coming from (presumably) an economist.

US Dollar 2,000 in a Single Online Day Due to its position, the United qc03 States offers a plethora of opportunities for those seeking employment. With so many options accessible, it might be difficult to know where to start. You may choose the ideal online housekeeping strategy with the help vz-31 of this post.

Begin here>>>>>>>>>>>>>> https://expertise02improved.blogspot.com/

When China invades Taiwan he's going to find out the importance of "warships"

That's the thing, until the missiles have been exhausted, the ships are kinda meaningless. And missiles and drones also override the need for artillery.

The latest entry in the warship argument is here, with links to the previous entries. Knock yourselves out.

I'd say it was clear that interest rates are no longer tightly coupled to either the stock market or employment, without any insight into why that should be the case. Animal spirits?

Eventually there might be a soft landing. Be patient.

I would say IRA and Chips act spending is counteracting the interest rate moves.

++ This makes sense to me, IRA spending is important as is...but maybe less so, the Chips act. We will see...Traveller

Yes, this is clearly the case, and further to that, the interest rate rises are avoiding further inflation by providing a countervailing influence.

and to a lesser extent, the war in Ukraine. Most of the aid is spent in the US buying weapons.

Most weapons are from bought and paid for and in storage. Go to Google Maps and look at the weapons in storage at Herlong/Honey Lake. Those M113's were what I worked on in the 1960's.

Yes, what we originally delivered to Ukraine was from storage. But those have been replaced and we have long since exceeded pre--invasion storage for what is commonly being delivered to Ukraine. I read an article recently that said artillery shell production went from 3000 per month pre-invasion to 29,000 per month now.

It's been reported that the Russians are firing as much as 20,000 artillery rounds A DAY. It would seem reasonable that the Ukrainians would like to overmatch that and fire 30,000 rounds back. That means that US artillery ammunition production can supply Ukraine with one day's worth of shells every month.

Another thing I see no mention of is the guns. I've seen reports that the life of a 155 mm cannon barrel is about 1,500 rounds, which means those 29,000 rounds a month of ammunition should be accompanied by about 19 new cannon barrels.

Warships in general may not be obsolete. But I believe carriers mostly are.

Why? Just curious.

Personally, I think they are more relevant than ever. Other warships are also not obsolete since their primary armaments these days are missiles and not just artillery. And, as long as there are submarines navies will need the subhunting capabilities of destroyers and the helicopters they carry.

They're far, far, far too expensive given their vulnerability. Sticker price for a single Ford class carrier is in the $20 billion range, I believe. But that's not including the full complement of aircraft, which adds another $15 billion. And then there's personnel costs. And supplies, fuel, etc. But you can't let a carrier float alone—it requires a complement of support warships.

Just an absolutely titanic amount of money for a weapons system that, at this point, can't even realistically take on our foremost geopolitical adversary, given China's robust capacity to make the waters off its coasts unacceptably dangerous for large targets. Sure, we can intimidate less powerful states, with carrier groups, but there are cheaper ways to deal with Iran.

Needless to say, even for America money isn't limitless, so the question isn't can we afford $70 billion for a carrier group, but rather, does spending that money on a carrier group weaken us relative to spending it on other things? I think the answer to the second question is unequivocally "yes." To me carriers in the 2020s pretty much scream "Battleships on the eve of WW2!"

I think that's the salient argument. 70 billion would buy a lot of infrastructure upgrades, especially to electrical grids and securing energy systems so they can't be crippled by some teenage hacker. The defense contractors just have more lobbying experience and have located themselves strategically (and bought the local representatives in charge of budgets).

There's a limit to how much of that you can do, though.

The waters off China's coasts are unacceptably dangerous for their ships also. The area is ringed by islands not controlled by the Chinese. Japanese islands are less than 100 miles from Taiwan.

Part of it may be that large corporations don’t depend on borrrowing so higher interest rates don’t slow them down very much. Part of the reason inflation was high was that large corporations were raising prices and blaming inflation. In fact, they simply increased profits.

Giants like Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook and such are making vast sums of money. They have so much money they are buying back stock because they have no other use for it. If this is true then why would a higher interest rate affect them?

Apple, for one, uses its cash to purchase capital equipment and place it in the factories of its suppliers. In this way no on needs to borrow money and Apple gets a secure source of product. Again, not interest rate sensitive.

Many people buy with credit cards and these rates are not sensitive to the federal rate, AFAIK. They are limited by law.

The only thing I can see that is very sensitive to this rate is home mortgages.

Most people stay in their homes for years or even decades. Out of the ones that don’t, the vast majority of them rent. Neither of those groups are affected by mortgage interest rate increases: the former because either they own their house outright or their (much lower) mortgage rate is locked in from years ago and the latter because, duh, they don’t have a mortgage. So I would guess the former is spending exactly the same as they were in 2021 before the rates crept up, and the latter is spending similarly to how they were in 2021 (depending on whether their landlord has jacked up their rents, and whether their employer has given them raises that cancel out the rent increases).

Existing homeowners are sensitive to interest rates through home equity loans, and originations of those loans are up compared to years past, even with higher rates. The slowdown in the housing market has meant more remodeling, which is often financed by loans (not to mention all the people using home equity for other expenses).

To a degree. People with money aren't letting interest rates stop them from buying, the rush to invest for Airbnb and such is still working itself out. Needs a whole lot more spectacular failures to warn off new entrants. People who want stuff like new cars are still buying them despite interest rates. Kevin keeps pointing out that most people are doing fine, that means household income is stable and people want to consume. The high interest rates just push those with lesser financial comfort margins out of the market.

Can you link to data showing that home equity loans have increased? I did not think this was true, but I may be behind.

Yes, because they're loaned at near the bottom rate. Banks had only a small headroom to offer discounts.

No way am I going to reup my HELOC at 7+%, or buy a car.

But people who need to do those things will do them. And I've seen some corporate-backed lending at 3% to keep the sales going. None I want to take advantage of, but it does keep people buying their cars.

Sure. Thanks for the nuance. Still, spending on home equity loans and remodeling is very different from spending on a newly issued mortgage, and both are different from not spending at all on anything because you're priced out of changing any aspect of your living situation. The first shows up as increased general economic activity: you buy more stuff at Home Depot, the people working at Home Depot and the people you contract with to do the work buy more stuff for their own households, etc. The second shows up as increased debt servicing: you shovel more money to banksters and they throw more parties on their yachts which sort of increases general economic activity too for the same reasons that spending it at Home Depot does, just not as efficiently as the first example as already-rich people stockpile some % of their money in assets, rendering it useless for awhile (until the asset is sold, generally, unlocking the stored value for a bit). And the third shows up as stagnation or recession.

Teacher has a gold star for you for being more correct than me... even though my point still stands. Existing homeowners are not really affected by rising mortgage rates, if they also just don't take out any more debt (home equity loans, remodeling on their credit cards, whatever). As an anecdote, I became a first time homebuyer in Jan 2022 before the rates took off. My spending has not changed at all due to the mortgage rate increases, because my mortgage is locked at the same payment for 28 more years, barring a tax increase or insurance increase. As far as I feel it in my personal checking account, mortgage rates haven't changed at all since Jan 2022. And as long as I don't take out a HELOC, I can keep spending as if it was still Jan 2022.

You;re ignoring that economics always looks at the margin. Yes, exisiting home owners aren;t hit by interest rate hikes *unless they have variable rte mortages.) But new home buyers are extremely affected by mortgage rate hikes. And new home buyers also buy the majority of fridges, stoves, furnaces air conditioners etc. etc.

This is not true and represetns a fundamental misunderstanding: large corporations heavily draw on credit, leverage in the jargon. (most large corproations are not Apple or Google)

What is true is large corporations in the USA during the long low interest rate period locked in significant amounts of debt at low fixed rates and thus are not equally exposed to current rate rises, however will become so progressively as funding lines are rolled over.

This equally is False: Many people buy with credit cards and these rates are not sensitive to the federal rate, AFAIK. They are limited by law.

Credit card rates are absolutely sensitive and indirectly based off Central Bank reference rate, and respond quite quickly to the rate - and in the USA they are not generally limited by law at all.

And here is a fine CNBC article conveying that your understanding of Credit Card rates in USA is entirely and 100% wrong:

https://www.cnbc.com/select/high-credit-card-interest-rates/#:~:text=Most%20credit%20card%20issuers%20offer,depending%20on%20the%20borrower's%20credit.

To Quote

Most credit card issuers offer a variable annual percentage rate (APR), ... [and] are often set by looking at the Federal Reserve’s benchmark prime rate, plus adding on a specific number of percentage points depending on the borrower’s credit. For example, the current prime rate is 3.25%. Meanwhile, the Chase Freedom® offers a variable APR ranging from 14.99% to 23.74%. Your interest rate will be somewhere in this range, but can also go up or down over the course of having the card.

[the article is updated but references the original writing date on the US Federal prime, however this is a mere detail]

You are on the right track but you need to go to make the next leap to see why an increase in the fed rate is less important than one might think. The prime rate at the time of that article was around 3% and the APR for that card was 15-24% .Prime is now around 8%. That increase of 5% is a lot but it is still dwarfed by the 12-20% that the credit card companies manage to tack on regardless of what is happening in the economy. Carrying a balance was always a fiscal disaster and now its a slightly worse one. I doubt that it is having much affect on people's spending.

On another note because I am too lazy to create a second comment; on the corporate side there were tax benefits to borrowing, particularly when doing it internationally, that are no longer as viable due to changes in US and EU law. It seems to me that companies are not taking out much in the way of new loans but are perfectly happy to keep their old low rate loans and switch to using cash on hand and current revenues to fund operations. I imagine that is why rate hikes are seeming to be uncoupled from the traditional effects they have had on the economy.

Certainly I will grant that specficially for CC the change in Basis may not for balance carrying persons really change things

On other hand in corporate borrowings (of which I am directly involved in, from USA for international) the bassis for a higher-risk profile dollar loan from US lender (for a US entity but with international) has jumped significantly.

This of course diverges signfiicantly from multinationals (meaning large enterprises), who are indeed going to be keeping existing low rate fundings.

Thus I do agree the effect of transmission is muted by the large stock of ultra low rate debt

But new borrowings for new projects and newer / younger / smaller companies are clearly jumping up in real csot.

The pandemic and the economic stimulus enacted to lighten at least its economic blow should make interesting fodder for economic study for decades to come.

The subsidized unemployment benefits -- which for a lot of low wage workers raised their income above what it would have been had they kept working -- are probably an interesting look at what universal basic income programs might do ... and in some respects, it looks like some extremely great things were accomplished.

Affected workers had free time and the burdens of economic anxiety lifted from them, many of them probably for the first times in their adult lives. They got to think about what they really wanted to do, maybe take some classes, and to look for employment that would pay them more. And many of them seem to have moved on to better, higher paying jobs.

And unlike tax cuts for the wealthy, their increases to income tended to get recycled right back into demand.

So for some things -- including of course the things that had relied upon low wage, miserable work -- there was inflation. But other than that, the trend countered the decades long and pathological shift of economic power from the working class to the wealthy, resulting (I hypothesize) in a relatively very robust economy.

Which creates inflationary pressure.

Now, the Fed's interest rate increases have not yet got inflation to where they like it (2% annually), but absent the increases, where would it be? A lot higher, I would think.

I cut my teeth in the late 1980s and early 1990s thinking 8% was a normal interest rate, and my reaction to the many pundits thinking that our current 5%-ish interest rates will soon be dropping is, what are you idiots thinking?

There is, I think, a natural human inclination toward demand, both in the way of consumption and in the way of investing in increased production. This is what allows real interest rates to be at least slightly positive without causing a recession.

How positive is an open question, and one that depends upon a lot of different factors. Among these factors, though, is how much someone's standard of living is raised by a little more spending, and for the low wage workers who were able to get better jobs thanks to the pandemic's enhanced unemployment benefits, the answer to this is, "A lot!" And such people are a more important part of the economy than they were when they were barely scraping by.

higher rates makes borrowing more expensive, but they also put money in the pockets of retirees and others who hold bonds

it probably doesn't completely cancel out the contractionary effect of higher rates, but it does introduce a bit of stimulus to balance things out

If you don't have to borrow, you likely haven't noticed the higher rates at all in your own personal spending.

(As I'm sure some armchair economists on here will correct me... you probably are still paying higher prices on stuff as the companies you buy from or bank you bank with or other people you deal with throughout the economy may be borrowing and paying those higher rates on their businesses and households... and so they pass some residual portion of their higher debt servicing expenses onto you. Plus, your circumstances could change at any moment, and you might find yourself putting a new fridge to replace the one that died on your credit card or taking out a HELOC for a new roof or having to eventually buy a new car to replace the old one... and then you'll notice the higher rates. But, if you yourself can avoid borrowing - which used to be called "living within your means" and which is totally possible for tens of millions of American workers to do with a little bit of discipline - you also will avoid almost all the pain of the higher rates happening right now, especially if your employer gives you realistic cost of living adjustment raises every year like retirees get with Social Security.)

This statement is just WRONG: It takes a year or two for interest rate changes to affect inflation.

Statistical evidence indicate that it takes 1-2 yrs for the FULL transmission effects of rate changes to complete.

That is NOT the same as "it takes a year or two" for interest rates to effect inflation and continuing to make this assertion based on a fundamental misunderstanding is.... mind boggling

That seems to be the sort of wrong that the Earth isn't round. A meaningless distinction except at the edges of calculations.

Actually it's a huge distinction. The fact that interest rates full impact is in 2 years allows that it has a noticeable impact in three months. In sysems/math terms, kevin is confusing the dead time with the settling time which are usually an order of magnitude in difference.

Further to this one can look to international data and cases of both Central Bank action and Non-action (see Turkey and hyper-infation) to see directly that the assertion is utterly not-true, based on a fundamentla misunderstanding of something that was read, evidently.

As a further comment on Transmission of Central Bank rate changes, not specific to US:

1.: Central Bank rate effects have both immediate effect and delayed effects. Rate rises or cuts impact inflation via the Cost of Funds and thus impact on level of economic activity which impacts demand, and of course demand impacts prices.

2: Short term impacts are via short-term rates. The specifics will vary according to the specific funding structure in an economy (e.g. in UK mortgage rates are not fixed over entire lifespan of the mortage but reset every 5-7 yrs - the US fixed mortgage 30 yr structure is extremely unusual globally).

A. Typical short-term immediate impacts are in (1) Consumer Credit as like credit cards or openl loans, which typically adjust immediately or on monthly or quarterly basis; (2) Business Working Capital lines (especially small-medium sized business), that is short-term / revolving lines which also typically reset off of Central Bank Reference rate contractually almost immeidately or on a rolling monthly or quarterly basis, (3) Short-term market debt (i.e. non-bank borrowings).

B. Medium term flow through ((>6months) are typically term bank credit particularly to businesses, but other borrowers as well.

C. Long-term - longer term fixed lending where rolling over notably on corporate but as applicable long-term consumer (I think frankly USA is near unique here).

It is all quite statistically clear if one pulls one's nose out of US centrism that there are both Developed Market and Developing markets that Central Bank rate rises impact inflation within a quarter but the full impact continues onwards in the economy for 1-2 years (where the specifics will depend on the financing structure in the economy, notably the various degrees of floating/variable rate lending versus fixed rate and as well the balance of terms (short-term, medium term, long-term [i.e. over 5 yrs])

At a first approximation fiscal actions are dominating monetary actions.

Maybe one can prudently say off-setting, perhaps fully off-setting, rather than dominating, but yes (fiscal for general readers = gov spending; and monetary = central bank).

Milton Friedman would claim that fiscal actions can't dominate or even offset monetary actions.

This is the only invariant in these conversations. I'm pretty sure I could find you saying the same thing after 2008.

It is incredible how little we all understand about the economy. Its even more incredible how little the economic experts understand and that we still consider them experts no matter how many times they display their misunderstanding.

This isnt a knock on anyone.

Yogi Berra will not be ignored.

Prediction is hard, especially about the future.

GDP per capita growth is what matters, not GDP growth.

2016 $59,000

2017 $59,900 1.5

2018 $61,300 3.0

2019 $62,500 2.0

2020 $60,200 -3.6

2021 $63,600 5.6

2022 $64,600 1.6

2023 $65,300 1.0 <-- slowest since 2020

GDP per capita growth is what matters...2023 $65,300 1.0 <-- slowest since 2020

Your claim implies US population increased by some 5 million in 2023. Which is, as Lounsbury might say, bollocks.

https://www.census.gov/popclock/?intcmp=home_pop

It's from Trading Economics; U.S. GDP per capita PPP

https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/gdp-per-capita-ppp

Here is GDP per capita from the Fed:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=1kCtq

It doesn't support your argument. I suspect that it is the 'PPP (currency) adjustment' in your chart that is doing all the work to create this narrative. Its always possible to find statistical support for the narrative you want to sell, but it's important to be clear that you are not showing GDP per Capita, you are using a different statistic.

Purchasing power parity adds inflation and trade imbalance to the mix and can be misleading at times because of the assumptions in the correlation.

Not sure where you're getting your gdp/capita numbers from, I would note that Kevin's pre-covid real gdp umbers were completely wrong.( I can't line up the numbers with the quarters becuse of the poor horizontal labeling the missing umbers should start with 1st quarter 2020, but the last present bar lines up over the first 2 in 2020.). Assuming Kevin's graph starts 1st quarter 2018, the actual BEA numbers for 2019 were 3.1, 2, 2.1.2.1 (2.33 avg) not 2.1, 3.2 4.7 2.7 (3.18)

Kevin's observation that the economy hasn't slowed reminds me of those who bemoan YIMBY policies because "rents haven't declined." Quite so, I reply: but maybe absent the new supply, rents would have increased 12% instead of the 7% we actually got.

So, too, with this economy, and the Fed's tightening. As I understand it the total tab for pandemic and post pandemic stimulative measures was around $5 trillion. Let's suppose for argument's sake that the optimal number would've been $3.5 trillion. So we ended up erring on the side of too much. Which I think was better than too little! Going big was the right call. We learned our lesson from 2008-2014.

In the parallel universe where we got it just right ($3.5 trillion) we might well be seeing similar growth right now (financing would be a lot cheaper, after all). But again, in the universe we actually live in, the stimulus number was $5 million. If the Fed hadn't acted when it did (even if it was too late, as some claim), we'd probably have seen higher growth still, accompanied by even higher inflation than the burst we actually experienced.

And yet as uncomfortable as the inflation burst was (and perhaps as sluggishly as the Fed acted), inflation has been mostly trending downward for the past eighteen months.

Anyway, this, in a nutshell, is how I see it: the economy possessed enough intrinsic strength that a robust 3% growth was what we've been gifted with even in the face of significant rate hikes, but, absent those hikes, growth would (for a while, at least) have been even higher—but in the bargain causing inflation to flirt with double digit levels.

There are numerous factors that we have right now that we've never had in the past.

First lets talk the boomer generation. For the most part they have paid off their houses and have money saved either in banks, or tied up in investment vehicles. They have started the process of wealth transfer to their kids through inheritance. this is helping the next generation accumulate wealth as well but, ALSO, ther are fewer of THEM then there are boomers so the wealth is concentrating in a smaller population

It is also interesting to observe that there are far more investment opportunities now then we had as boomers, Mutual funds, IRAs, etc were not in existence "back in the day".

As all of this has transpired we (boomers) are living longer and spending more (because we can afford to) and there's fewer workers to provide the goods and services we want. So, employment has remained steady while spending has increased and a lot of that spending we are doing is on leisure activities (or fun stuff), as opposed to housing etc (necessities)

When the boomers completely die off is when the crap will hit the fan. We will see the building boom collapse. I think that will happen within the next 20 years or so. House prices will fall in MOST markets.

The boomer generation was a gross anomaly in birth rates that will have had generational affects on the economy. ALL previously determined standards will have to be revised.

We are entering uncharted territory here and old paradigms will have to be refigured.

I don't see much of a building boom. In fact, people keep pointing to how housing has never fully recovered from the Great Recession.

I expect housing prices to be stable in urban and suburban areas (we are still seeing movement into cities from rural areas), with continued strong increases in the biggest metros, and selected rural areas will also be fine (immigrant workers in food processing areas and 2nd homes in vacation areas).

I'm not convinced that simply raising the rate that the Fed pays on deposits is exactly the same as open market operations. If the Fed sells bonds, it is not only removing money from banks that they might otherwise lend, it is removing money from everybody that would rather have the bond than some other investment or purchase. My own theory is that the Fed is acting on the principle that if the only tool you have is a hammer, everything must be a nail. The current drivers of inflation are fossil fuels, which aren't very responsive to changes in interest rates, rent which if it is responsive at all will go up with higher interest rates as fewer residences will be built, and price gouging by monopolists.

Good points. There are two plausible mechanisms where higher rates contribute to inflation. Higher costs for businesses being passed in to consumers, and government interest payments (a trillion this year, I'm told) adding to aggregate demand.

Kevin, if you think Jerome Powell has any more of a clue than you, well... nah.

"In the past it's taken real rates of around 4% to touch off a recession." Where in the world does this idea come from? It's certainly not in the actual data:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1kCbP

When economists, let alone bloggers, believe in things like this, it's no wonder that predictions are usually wrong. The inflation of 2021-2 actually contradicted several assumptions that the Fed operates on, yet there seems to have been no change in beliefs.

GDP growth slowed between 2021–22 and 2022–23. It's right there on your chart.

I can't think of any rationale for believing that inflation can only be curbed by making growth slower than it was before inflation picked up. Why not just look at what GDP was doing during the inflation spike?

Many, many, many economists, wise economic talking heads and economic literature did (and still do) argue that growth would need to be slowed much more dramatically in order to tame inflation. Many members of the Fed certainly believed in this rationale.

In 2021/2022, the mainstream position was not that we needed to slow growth only a small amount and just dip under the fast growth rates of 2021. We needed a dramatic slowdown. But that didnt happen.

If you believed that massive, unprecedented covid related supply contsraints were responsible and would fix themselves without a slowdown or higher rates, this mainstream position didnt make sense. But there was certainly plenty of rationale going around.

Such economists and some Fed governors may think that, but other economists think they're wrong. The whole idea of a "soft landing" is based on thinking that a drastic decline in growth is not necessary.

If you have references from 2021 where Jerome Powell projected very low growth, or even a recession, as a necessary corrective for the inflation of the time, I'd like to read it. I don't believe that was the plan.

Well sure, but what you are saying here is not consistent with your claim that there is no 'rationale for believing that inflation can only be curbed by making growth slower than it was before inflation picked up'.

My point was that many knowledgeable people thought that very thing. Certainly not everyone agrees.

Im sure that Powell is wise enough not to make specific predictions like that, but the Fed puts out regular projections of what they think future inflation, unemployment and GDP growth will be. Check out the December and Sept 2022 FOMC Summary of Economic Projections. They were pretty clear that they expected a recession or nearly a recession in 2022 and 2023 in order to get inflation down.

Thank you! I concede that there is a rationale, and it is subscribed to by many people, although not by such figures as Paul Krugman, Kevin Drum, and Jay Powell. What I should have said is that I don't think that rationale is necessary to justify the Fed's rate hikes. The Federal Open Market Committee is not dominated by such inflation hawks. If it were, they'd have kept the rate hikes coming, and we'd have had their sought-after recession by now. Team Soft Landing is actually in charge.

New housing is key to unraveling the story. New housing starts, construction and the related employment is a key mechanism though which higher rates usually strangle the economy, reduce demand throughout all areas and temper inflation.

While housing and housing employment have stagnated, they have stayed at a level higher than it was prepandemic.

This is unusual. Other unusual items are the large infrastructure legislation, very large wage increases for lower income workers and the ongoing stimulus from the tidal wave of home refinances in 2020-2021.

A piece of data to consider is Houses Sold by Finane Type:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=1kCgu

While mortgage sales have fallen, cash sales have increased. Also unusual. While there arent a huge number of cash sales, it seems indiciative of something that is likely being missed in the traditional guesstimates of economic predictions.

"While mortgage sales have fallen, cash sales have increased."

The rich have money, nothing productive to put it in, and so are buying up property as a store of all that money. It's a sign that tax rates are too low on the rich, especially the ones who don't have to labor for their money, and just receive it "passively" (e.g. inheritances, stock investments, being a stockbroker who gets to reclassify their wages as "capital gains," etc).

How would a stock broker reclassify their wages. Investment fund managers get to do that.

I only know two things for sure about inflation. One is that I don't understand it. The other is that Jay Powell doesn't either. And there's a corollary to the second, Uncle Milty Friedman also didn't.

I see three factors contributing to the rapid growth and spending:

1. The IRA and Chips act are pretty strong stimuli

2. Immigrants are net contributors to economic growth, and immigration has been surging. Why people want to restrict immigration is a mystery to me.

3. Wages have risen substantially, especially for the bottom quintile. The lowest incomes spend the largest part of their income, and spending has been on a tear.

Taken together, these three factors are contributing to really substantial economic growth, which is bound to have an effect on inflation. Perhaps we need to re-think the 2% target.

Immigrants working also increase supply which will reduce inflation. The problem with increasing interest rates to slow economic growth is that economic growth can increases supply and thus reduce inflation. You want to slow growth only if the growth is in 'unproductive' parts of the economy. A fundamental problem with our gdp numbers is that if we start with producing 5 units of cars for 5000 units of money we claim the same gdp growth rates if we produce the same 5 units of cars for 7000 units of money or 7 units of car for the sane 5ooo units of money. The first is inflationary the 2nd is disinflationary.

Not an economist, but it seems to me raising interest rates while using deficit spending is like using the brakes and the gas pedal at the same time. You can chug along that way but it ain't good for the car. Not to say deficit spending is wrong; it's just staying very high compared to the aftermath of past stimuli.

Kevin is getting confused again. The Fed does not control RGDP, they control NGDP. NGDP has gone down by A LOT. This is only confusing because Kevin does not understand this.

But NGDP is also quite a bit higher now than it was pre-covid. You seem confused. Or are we just straw-manning here?

You answered your own question -- "even now real rates are only about 2%. In the past it's taken real rates of around 4% to touch off a recession" -- don't you think?

The rate wasn’t sufficiently high enough to affect the trajectory of spending/consumption and its effect on inflation is illusory given the exogenous nature of its rise.

Recall that prior to the Great Recession, the Fed rate was typically higher than it is today.

I'm not so sure about the notion some people have about deficit spending offsetting rate increases. Public consumption (gov't) as a % share of total GDP is at its lowest since the immediate period after WWII.

I'm also not so sure about the idea that people are borrowing more in order to spend more. Evidence points to a lower rate of increase in total consumer credit and a lower personal savings rate.

With that last point, it seems consumer spending hasn't declined primarily because consumers are dipping into their savings to make up for the gap between earnings and consumption and expanded government subsidies. Note how total bank deposits have been flat for the last 2 years.

For more than 2 years now, the Beveridge Curve has been vertical. Curious, no?

https://www.bls.gov/charts/job-openings-and-labor-turnover/job-openings-unemployment-beveridge-curve.htm

Why is the economy so good?

Bidenomics!

I'm only partly joking (and I'm 100% not an economist), but isn't it generally agreed in economics that more money ending up in the hands of low and middle-income people will have a more stimulative effect than more money ending up in the hands of wealthy people?

And isn't that's what's been happening over the past 2-3 years?