A few days ago I wrote that our overall response to the COVID-19 pandemic had been pretty good, all things considered. I also mentioned that my post was basically a reply to Lawrence Wright, who argues that our pandemic response has been "one of the greatest failures in the history of American governance." He bases this on three big mistakes:

- In early January, the CDC failed to get China to cooperate with an investigation.

- In February the CDC botched the development of testing kits.

- In March, the CDC fumbled on mask wearing and eventually made a U-turn.

This struck me as laughably thin. Wright admits that #1 is the fault of the Chinese and there was nothing we could have done about it. #2 is real, but I doubt very much that it had much of a long-term effect. Europe had tests earlier than us and their outbreaks were just as bad.

As for #3, the CDC could have done better. But there really was new research being done in real time, and it was only slowly that mask wearing was tested as a way to prevent the spread of the virus. Previous research had been mostly about protecting the mask wearer, and the CDC was correct in saying that this was of limited use. European countries were in the same boat, and they changed their minds at about the same time we did.

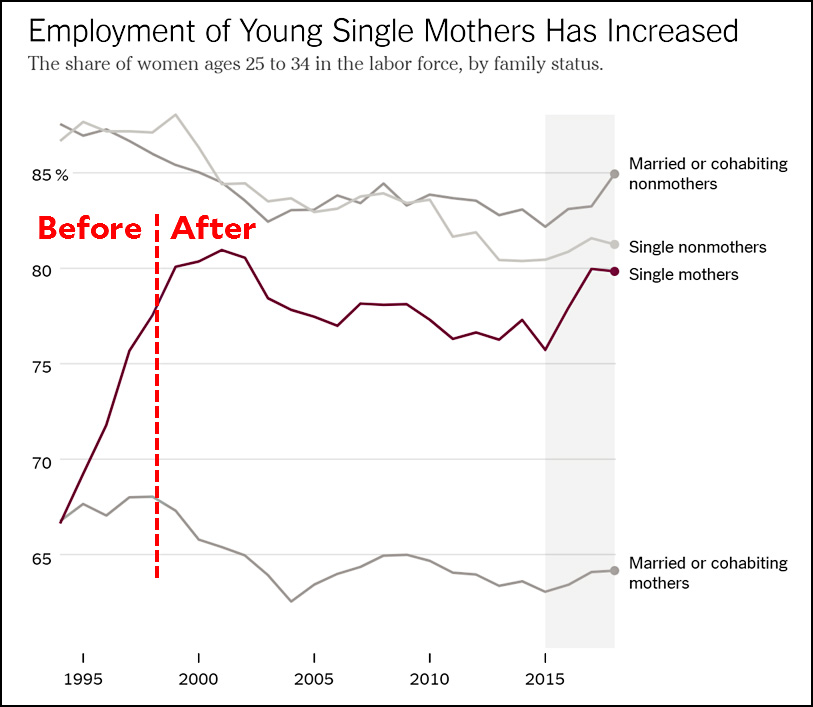

All in all, this just isn't the devastating indictment Wright thinks it is. But the funny thing is that he missed the truly greatest mistake we made. Take a look at this chart of COVID-19 deaths:

This is a chart of all European countries plus the US. In the early days, the US is at the low end of the pack. Despite our missteps, we're not doing too badly. But during the summer of 2020 the pandemic dies down in Europe but keeps shooting up in the US. By November we're doing worse than all but four or five European countries.

Why? Because Donald Trump insisted on reopening the economy too soon. Unlike Europe, we never crushed the virus to near zero. Instead we kept on killing people all through summer, and when winter came we were starting from a higher base. I think it's safe to say that this one mistake probably cost a hundred thousand lives or so.

This is why I rate our overall response to the pandemic as "pretty good." We really didn't make as many deadly mistakes as people think, and overall the CDC and FDA did a fairly reasonable job. The one big mistake we did make came down to a single sociopathic man whose motivations, as always, were beyond human ken. Electing Trump president was our only real mistake, and we did that long before anyone had ever heard of COVID-19.

NUTSHELL VERSION: We mostly responded fairly well to the pandemic, especially given how new it was and how the science behind it was changing rapidly in real time. On the vaccination front, our response has been all but miraculous.

We made only one big mistake: allowing Donald Trump to be our president. My take is that this is not enough to condemn the entire US response. It's only one thing. On the other hand, it was a big thing and we did elect the man. If you think it's sophistry to say "it was only one thing" when the result was so catastrophic, I can't really blame you. I think it's important to understand just where we went wrong, but I'm less concerned with how you then describe it.