Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through May 25. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Cats, charts, and politics

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through May 25. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Well, this is embarrassing. Not only is this not Mount Whitney, it's not within a hundred miles of Mount Whitney. A look through the original series of photos tells me that this picture was taken while heading south on US 395 just before the Mammoth Lakes exit. That makes it Laurel Mountain . . . I think? Which clocks in at a puny 11,818 feet.

The original post, in all its mistaken glory, is below.

This is Mount Whitney, highest mountain in the contiguous US at 14,505 feet. It beats Mount Elbert in Colorado by 65 feet, which just goes to show the misfortune of being #2 by even a tiny amount (less than half a percent in this case). After all, who's ever heard of Mount Elbert?

I chose to render this in shades of gray instead of the high contrast that's more typical of black-and-white alpine photos. Not only was this more faithful to my recollection, but it just seemed right.

QUIZ: Everyone knows that Denali is the highest peak in the US. Without looking it up, what's the second highest?

It's pet peeve time! Perhaps you've seen this image:

The one on the left is the original. The bowdlerized one on the right is the image that went into the Bartram Trail High School yearbook after the faculty advisor decided to hide the cleavage from 80 different pictures of senior girls. We have been assured that many of the alterations are clumsier than this one, to the point where they almost look like parodies.

Make no mistake: this was a dumb thing to do. So what's my peeve?

Here it is. This dumb little local squabble has been on the main page of the Washington Post for three days. It was on the main page of the New York Times. It was on the main page of the Guardian. Also the BBC, USA Today, CNBC, HuffPost, the New York Daily News, the New York Post, NPR, CBS News, NBC News, and probably others. I'm not counting any of the dozens of mentions it got in local media.

In the dim past—20 years ago?—this would have remained a dumb little local controversy in St. Johns, Florida, which is exactly what it deserves. Today it gets national attention. Why do we keep doing this? In a country the size of the United States, there are dozens of these neighborhood kerfuffles every day. They mean nothing. And yet, because they're clickbait, national news organizations blare them as if they're real news. As a result, everyone ends up believing they are real news and a thousand Twitter ships are launched in outrage.

Stop it.

Is it better to ignore assholes who live for publicity, or do their lies need to be highlighted and fought to prevent them from settling in by default?

This is an eternal question, but I would like to suggest that in the case of Marjorie Taylor Greene the answer has become obvious: ignore her.

Please.

Here's a baker's dozen list of the reasons for vaccine hesitancy in the United States:

Every one of these requires a different approach. Some are probably hopeless, including religious objections and right-wing paranoia. Others, like the fertility urban legend, might be amenable to plain informational campaigns. Concerns about long-term safety are a tough nut, since obviously we can't honestly say for sure that we know this is unjustified.

In any case, the lesson here is to forget about the partisan noise. Let right-wingers do what they want and instead focus our attention on all the other vaccine-hesitant groups. They're far more likely to be persuadable.

This is a surprisingly difficult number to get a handle on. The CDC provides us with the following approximate figures since vaccinations started through April 26:

By the end of this period, about 100 million people were fully vaccinated and 200 million remained unvaccinated. This means that as an average over the entire period, 50 million people were fully vaccinated and 250 million remained unvaccinated.

Put this together with the hospitalization figures and the final tally tells us that 548,000 out of 250 million unvaccinated people were hospitalized vs. 2,000 out of 50 million vaccinated people.

This means that about 0.22% of the unvaccinated population ended up in the hospital with COVID-19 compared to 0.004% of the vaccinated population. That's a difference of 55:1.

In other words, if you are unvaccinated, your odds of getting a case of COVID-19 serious enough to require hospitalization are 55 times higher than they are if you get the vaccination.

Why such a big difference? There are two factors. First, the vaccines prevent infections by a factor of about 10-20:1. Second, if you are infected, the vaccines help to prevent you from getting a serious case. Put those two things together, and you get the 55:1 difference in serious infections.

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through May 24. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

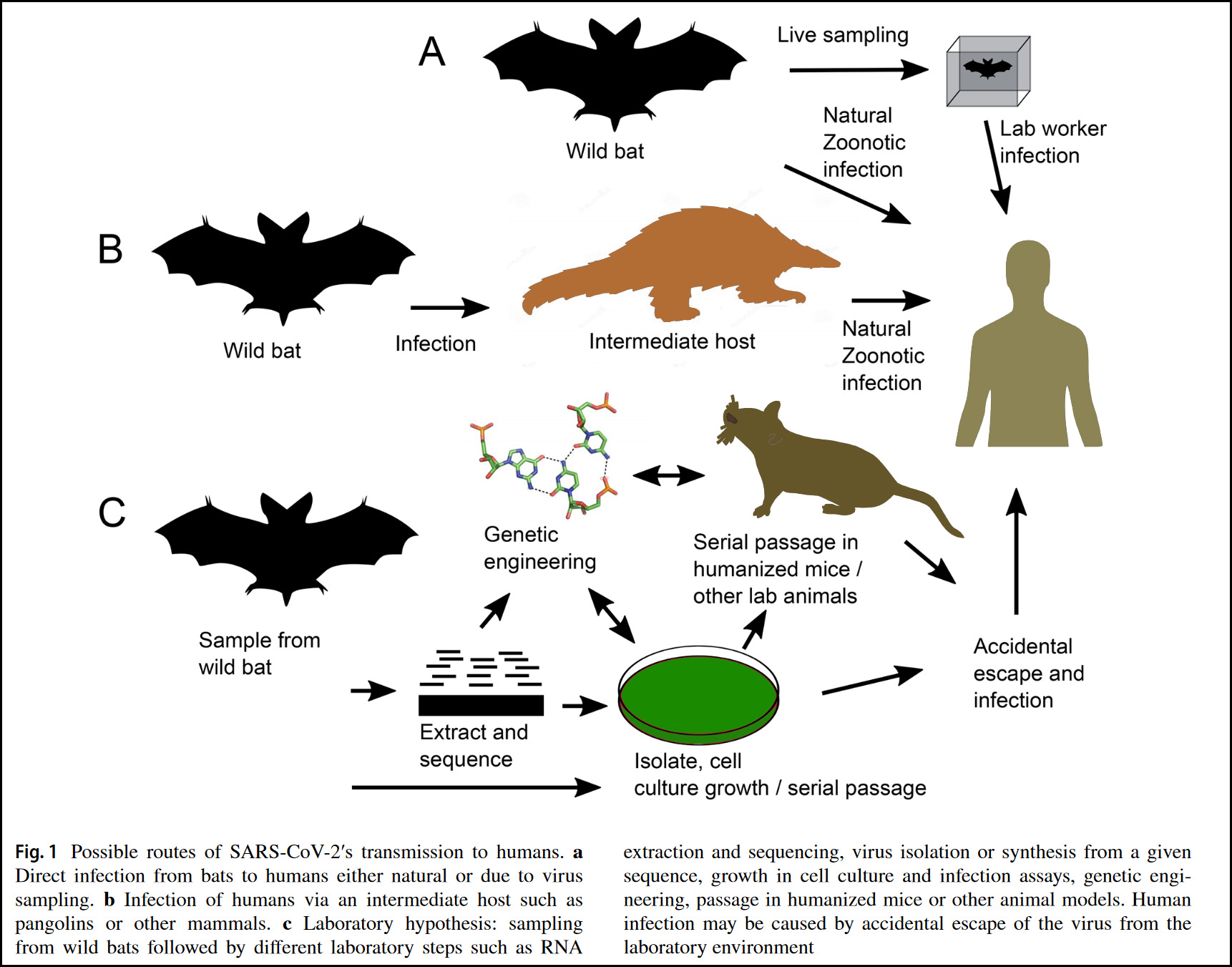

Are you wondering why the "accidental lab release" theory of the coronavirus has been getting more attention lately? It's not because there's more evidence in its favor. Just the opposite: It's because the evidence of a zoonotic origin has been getting harder and harder to sustain.

As you may recall, the initial theory for the origin of the coronavirus had to do with transmission via wet markets in Wuhan. That theory was abandoned pretty quickly when it turned out that several of the very first victims had no connection to the wet markets.

The work after that centered on bats, which are huge reservoirs of coronaviruses. However, since there are no bat viruses that are good candidates to be a SARS-CoV-2 precursor, scientists began searching for intermediate hosts. You probably remember this. Palm civits were candidates at first. Raccoon dogs were on the list. Or pangolins. Or minks. Or ferrets.

For various reasons, all of these intermediate hosts had problems that made them unlikely candidates. At first this wasn't a big issue: it was early days and the search continued.

But eventually days turned into months and then into more than a year. And still no likely intermediate hosts had been identified. We're now at a point where it's been nearly a year and a half and we still have no good theory of zoonotic origin.

That doesn't mean the lab release theory is correct. It just means that it's natural for it to get more attention as the zoonotic origin theory becomes more and more difficult to find evidence for. One problem, though, is that even if a bat virus did escape accidentally from the Wuhan lab, it would still need an intermediate host to evolve into something transmissable to humans. So the lab theory faces the same problems as the zoonotic theory.

There's much more to the story, of course, including the fact that the SARS-CoV-2 virus is unusually efficient at infecting humans. However, this cuts against both theories. Even given the fast mutation rate of coronaviruses, it's difficult to figure out how it could become so good so fast in the wild. On the other hand, any lab release theory that assumes the virus was good to begin with implies not just that the Chinese were careless, but that they were deliberately engineering a coronavirus with a spike protein that was designed for maximum harm to humans. There's strong genomic evidence against that, and in any case it requires you to believe that the Chinese were both unbelievably careless and were engineering a bioweapon of some kind. That's kind of hard to swallow.

In other words, it's worthwhile keeping an open mind on this. On the one hand, the Chinese have been so aggressively uncooperative that it's hard to believe they don't have something to hide. This favors the lab theory. On the other hand, we shouldn't let the current lack of success on the zoonotic front provoke us into giving up out of frustration and turning to simpler theories featuring well defined enemies that we never liked much in the first place. Science runs into tough roadblocks all the time, and in another year maybe some genius will have a lightbulb moment and we'll finally have a fleshed-out theory of zoonotic origin that makes perfect sense. This calmer mode of thinking favors the zoonotic theory.

This whole thing might remain a mystery forever. Alternatively, maybe some lab worker from Wuhan will escape to the West with concrete evidence that the virus was manmade. Or else someone will finally come up with a convincing zoonotic story. Stay tuned, and in the meantime don't get too attached to either side.

POSTSCRIPT: Just to be absolutely clear here, my point is that expert opinions about the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus haven't just changed for no reason. They've changed because the evidence has changed. The only tricky part is that what changed isn't evidence for the lab theory getting better, but evidence for the opposing theory getting worse.

My mother and I were up at the Farmer's Market on Saturday, and this little cutie pie was at the table next to us. He was very well behaved, but obviously interested in all the delicious food being eaten around him. I'm not so good at dog breeds, however, so I'm not sure what kind of dog this is.

UPDATE: The best guess from comments is that this is a Shiba Inu, a "superb hunting dog" according to the world's finest reference sources.

Tom Friedman says that Joe Biden can win a Nobel Prize if he just manages to broker permanent peace between Israel and the Palestinians. I don't doubt that for a second. Hell, you could rename it the Biden Peace Prize if he did that.

But as the Beatles said, we'd all love to see the plan. It's just a lot of hot air unless you can offer up a proposal that, even in theory, both sides are willing to accept. So go ahead. I promise not to laugh.