How effective is preschool? There is, to put it plainly, much research has been dedicated to this question and we still don't know for sure. One constant, however, is that every discussion of pre-K includes a reference to the Perry Preschool Project, a smallish study done in 1962 that provided high-quality preschool to poor Black students beginning at age three. But it's frankly tiresome to keep hearing about it, since it's now 60 years in the past and included only about 60 kids in the treatment group. If we haven't come up with better studies by now, we should just give up the whole thing.

However, the PPP does have one advantage over other studies: It took place 60 years in the past. This means that it provides a unique look at participants throughout their entire lives without any guesswork about things like expected future income or criminal activity. By now, that information is all available directly. A team of researchers has done just that and their conclusion is pretty simple:

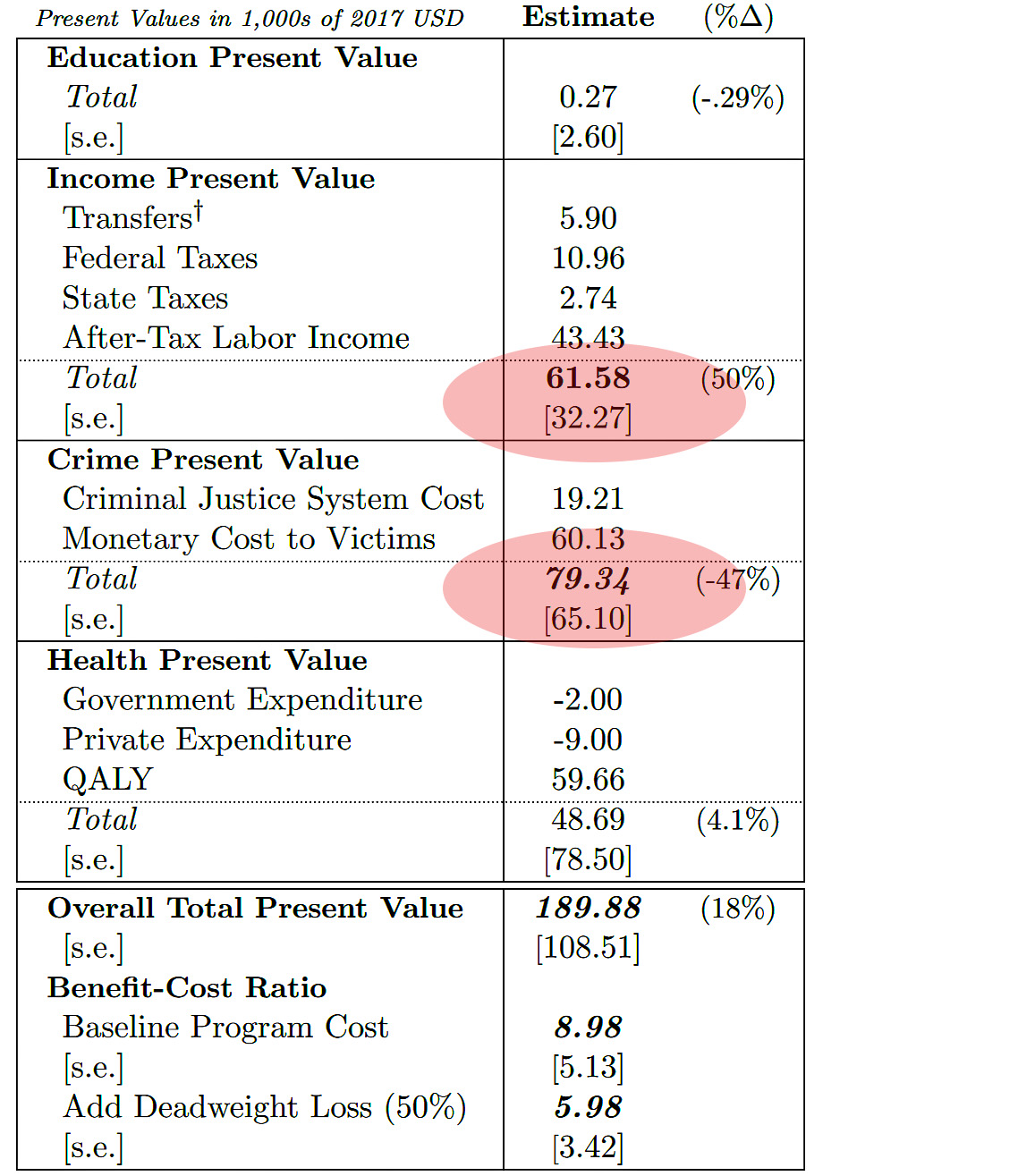

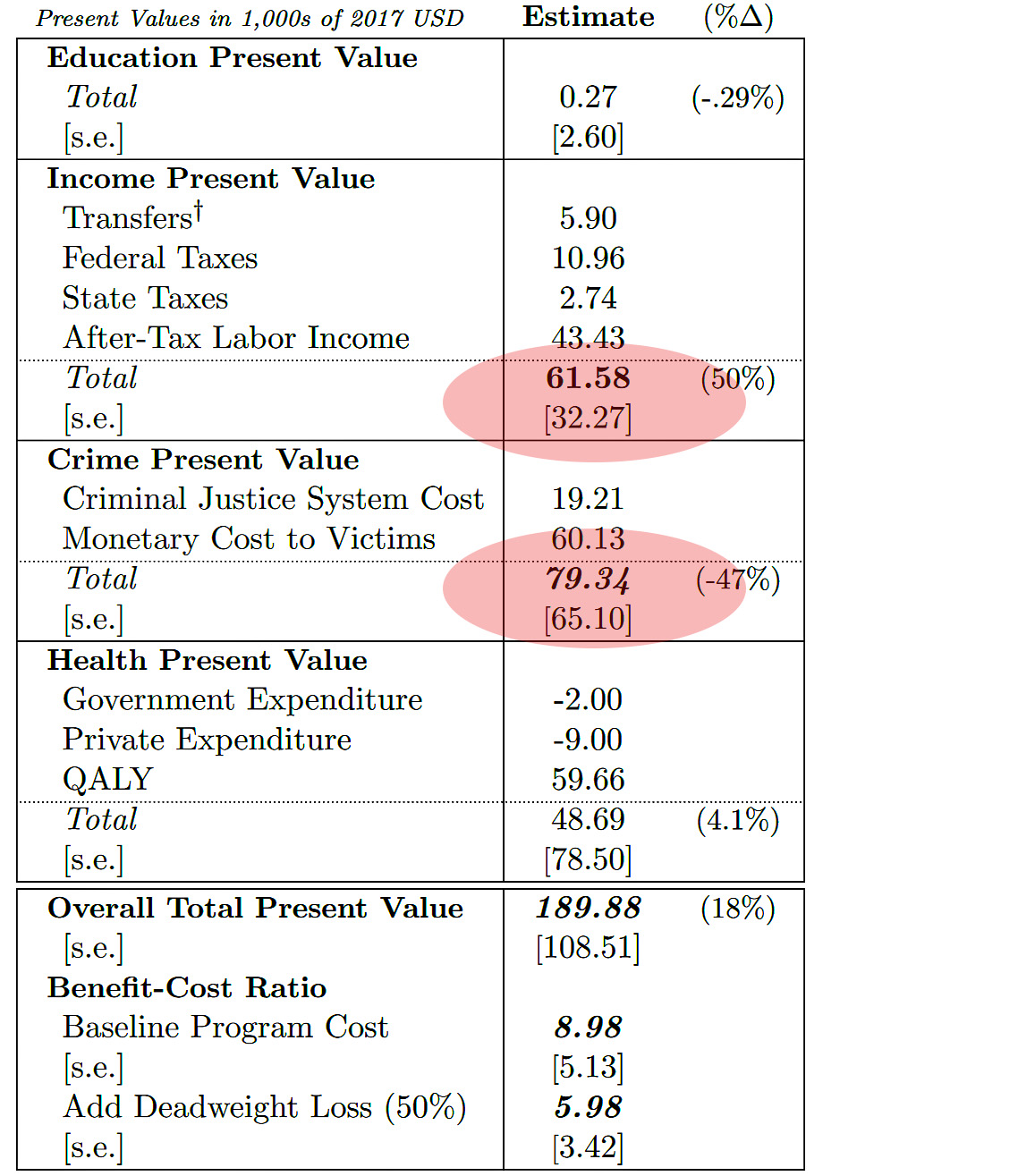

The authors present benefits in terms of present value dollars, and they find that the effect of PPP on education is minimal. Ditto for health care. However, the impact on income and crime is considerable. Graduates of PPP ended up earning substantially more than the control group and engaged in substantially less crime. Nearly all of these benefits came between the ages of 16 and 40.

This is consistent with other studies of pre-K, which generally find that preschool doesn't make you smarter or better in the classroom. Rather, preschool seems to improve life outcomes by instilling good cognitive habits in other areas.

This is progress, and it makes a good case for universal pre-K. However, it still leaves the basic Black-white education gap in place, with Black kids graduating from high school with an average 9th-10th grade reading level compared to 12th grade for white kids. Until we figure out what to do about this, our education problems in the Black community are very far from solved.