This is a picture of the Providence Mountains near dusk. It was taken in the Mojave National Preserve about 90 miles east of Barstow.

Cats, charts, and politics

This is a picture of the Providence Mountains near dusk. It was taken in the Mojave National Preserve about 90 miles east of Barstow.

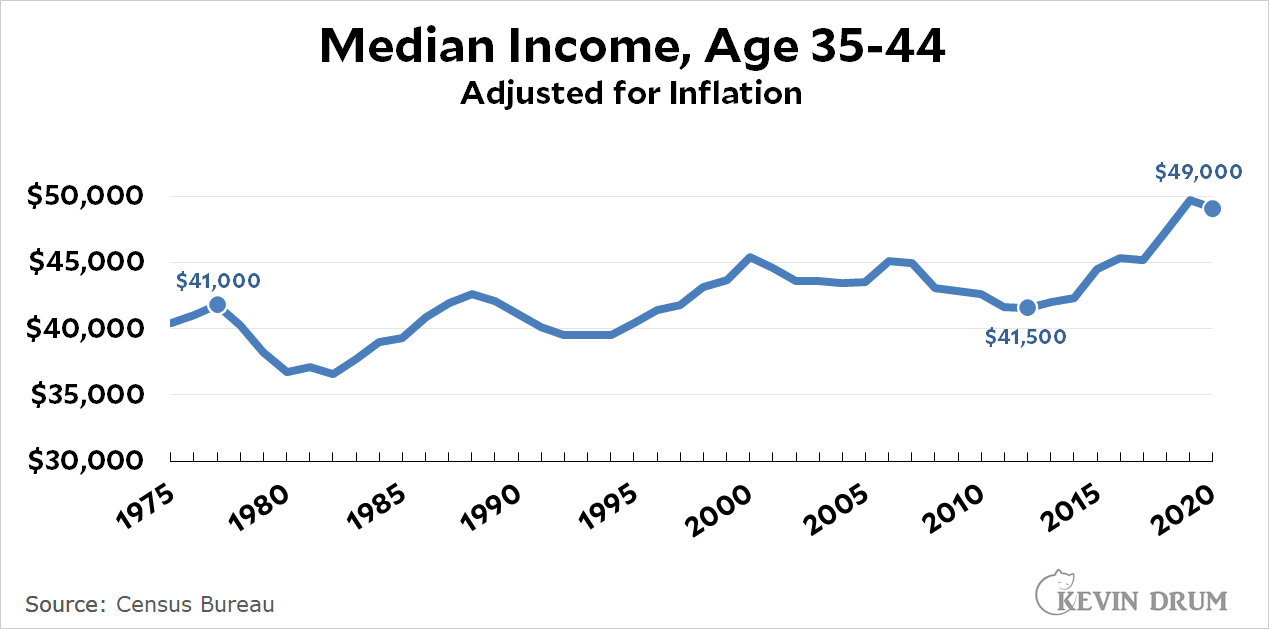

I mentioned in an earlier post that conventional wisdom remains stuck in the belief that middle-class incomes have tanked, and this belief hasn't really changed even though it no longer fits the facts of the past few years of strong income growth.

But things are more complicated than that, and I thought you might be interested in seeing a few different ways of measuring middle incomes. None of these is "right." They're just measuring similar but different things.

First up is your basic measure of median income from the Census Bureau:

With a judicious choice of starting point, it was easy at the end of Great Recession to say that incomes had been stagnant since the '70s. However, even this chart can't avoid the fact that since 2012 the median income for prime-age workers has increased by nearly 20%. The stagnant income story, whether for Millennials or anyone else, just doesn't wash anymore.

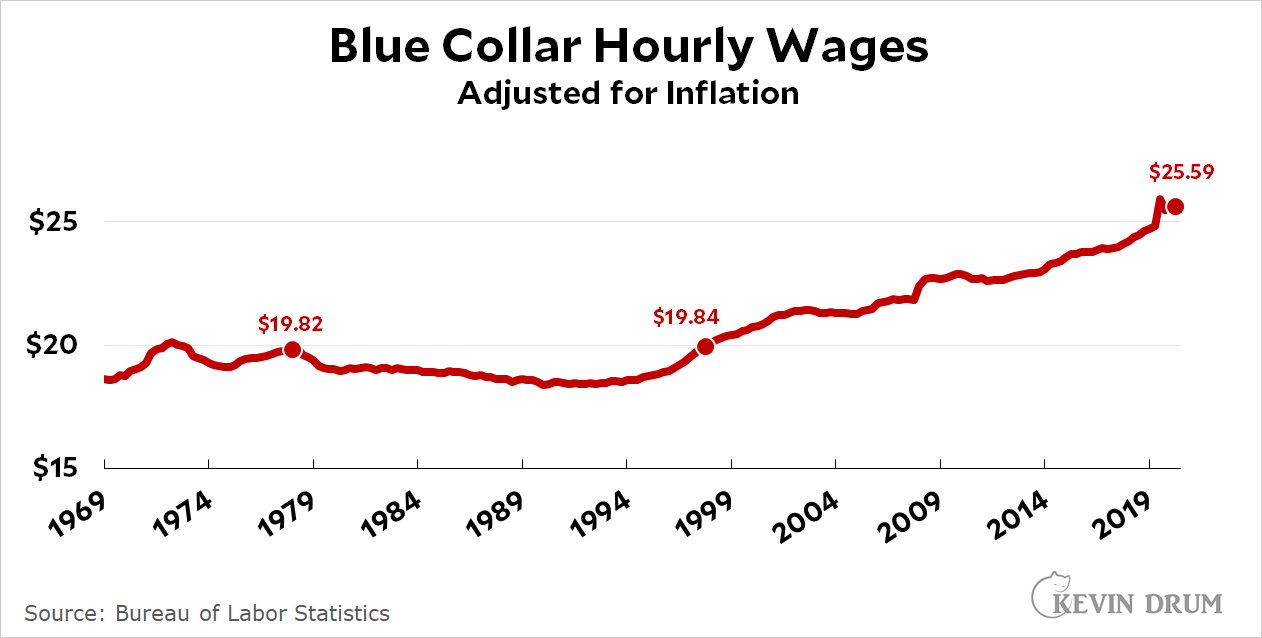

But there are other ways to measure income. Here's one:

This is a measure of "nonsupervisory" wages, which is basically blue-collar wages. In this case, it looks like wages are stagnant or down all the way through the late '90s, but have grown nearly 30% since the year 2000. The timeframe is different, but it once again shows that the conventional wisdom of stagnant wages has passed its sell-by date.

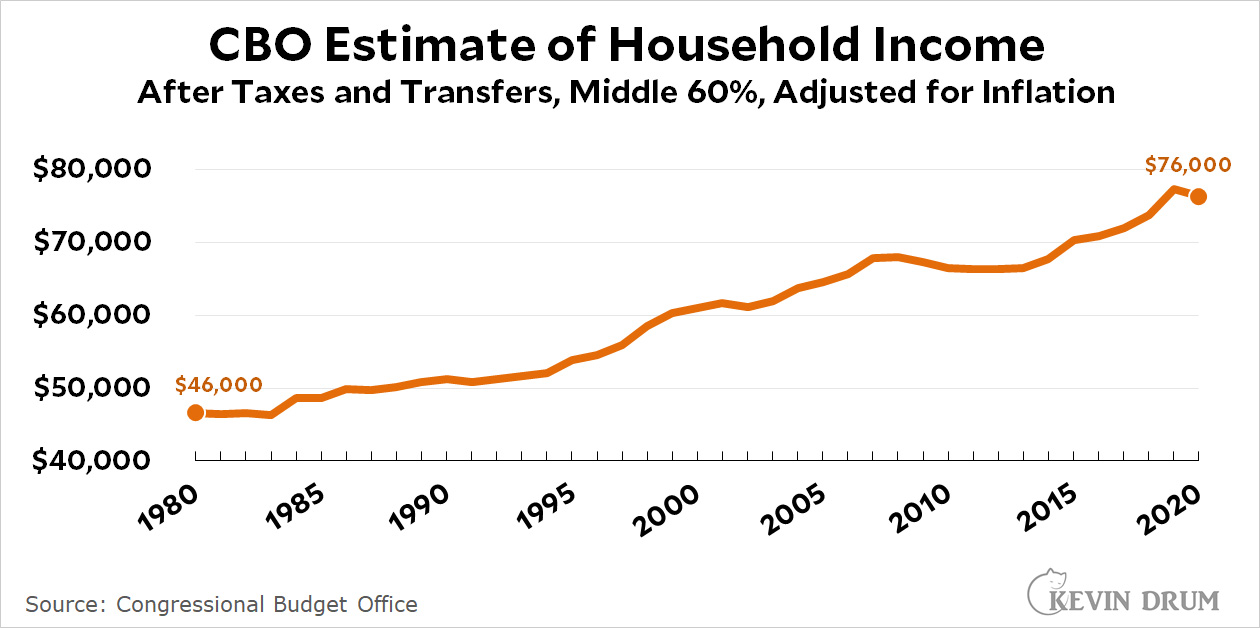

Finally, here's a third way of measuring income:

This is an unusual measure of income. It's after-tax income adjusted for benefits from government programs. It covers the middle 60% of the population, which is basically the bottom of working class to the top of middle class. What it shows is that middle incomes have been steadily rising for the past 40 years and are now 65% higher than in 1980.

There's a flat spot from the start of the Great Recession through about 2014, but that's hardly surprising. Since then, incomes have risen 15%.

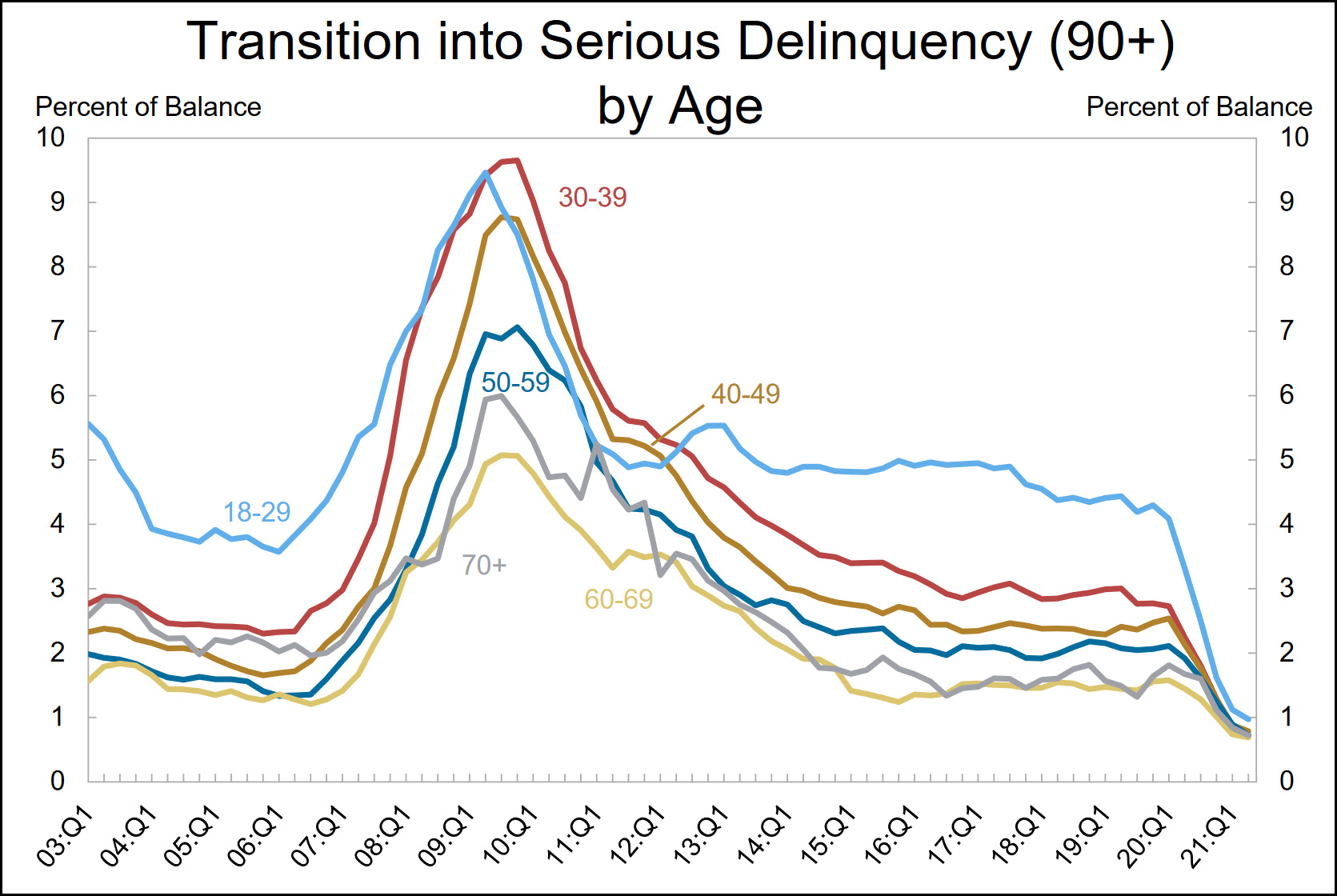

In addition, consumer debt has declined by a third over the past few years; bankruptcies are almost down to nothing; and delinquent loans have plummeted for practically every age group.

Depending on which of these income metrics you believe, the conventional wisdom of stagnant middle-class incomes has been obsolete since 2015, since 2000, or was never really true at all. But one way or another, it's obsolete now.

None of this is meant to suggest that the economy has been great for the middle class. Both the rich and the poor have done better, and over the past few decades the growth in middle-class incomes has been a weak 0.5-1.5% per year depending on which measure you use.

Still, at the very least middle incomes have grown over the past six or seven years, and it's no longer accurate to talk about stagnant wages no matter what measure you prefer. Too many people seem to have ignored this.

POSTSCRIPT: It's worth noting that this is merely raw data, as the headline says. You should use it if you care about accuracy.

However, it remains the case that income growth has been worse for the middle class than for anyone else, thanks to massive growth among the rich and big growth in government assistance among the poor. If you wonder why the middle class feels squeezed, this is part of the answer. They feel like everyone else is doing better, and they're right.

I've been derelict in covering the day-to-day news out of Washington, so let's catch up with what Democrats are up to.

First off, there's the $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill. Thanks to help from Republicans it passed in the Senate last month with 69 votes, well over the 60 needed. It is now waiting for action in the House. Centrists love this bill.

Second, there's the $3.5 trillion omnibus spending bill, which hasn't yet passed anywhere. It's a reconciliation bill, which means it needs only 51 votes, so Democrats can pass it all by themselves. Unfortunately, two Democrats, Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, aren't on board. Even more unfortunately, neither Manchin nor Sinema has made it clear just what changes they want to the bill. This is very odd, but that's where we stand.

Progressives love the $3.5 trillion bill. Centrists are not so keen on it.

But hey—at least the infrastructure bill will get passed, right? That's less clear than you'd think. Right now, Nancy Pelosi is holding it up because she wants to pass both bills as a package. She's afraid that if the infrastructure bill passes by itself, centrists will have gotten everything they want and will bail on the omnibus bill. House progressives agree, and have threatened to vote against the infrastructure bill even if Pelosi brings it up for a vote.

So that's where we are. Progressives won't vote for the infrastructure bill unless they can also vote on the omnibus bill. But Manchin and Sinema are holding up the omnibus bill and refusing to say what it would take to get their votes. It seems beyond belief that both bills might fail, but right now that's a distinct possibility.

Finally, winding around all of this, is a third bill. We are once again getting close to our debt ceiling, so Democrats need to pass a bill to raise it. Republicans are just laughing at them and declaring that they'll filibuster a debt ceiling bill just to create chaos.

One solution to this is to put the debt ceiling increase into the omnibus bill and pass it solely with Democratic votes. In fact, Democrats could even vote to eliminate the debt ceiling entirely. However, the leadership of the party has refused to do this for reasons that I haven't quite sussed out. Instead, they plan to introduce a "clean" debt ceiling bill and make Republicans vote against it. I guess they're gambling that in the end Republicans will buckle when the government shuts down because we can no longer fund it all. We'll see.

Helluva mess, isn't it? This is what happens when you have a 50-50 Senate and have to satisfy every single senator.

The Wall Street Journal reports that Chinese president Xi Jinping has grown weary of capitalism and is waging a campaign to put the Chinese economy more firmly under the thumb of state control:

Xi Jinping’s campaign against private enterprise, it is increasingly clear, is far more ambitious than meets the eye....He is trying to roll back China’s decadeslong evolution toward Western-style capitalism and put the country on a different path entirely

....In Mr. Xi’s opinion, private capital now has been allowed to run amok, menacing the party’s legitimacy, officials familiar with his priorities say. The Wall Street Journal examination shows he is trying forcefully to get China back to the vision of Mao Zedong, who saw capitalism as a transitory phase on the road to socialism.

Mr. Xi isn’t planning to eradicate market forces, the Journal examination indicates. But he appears to want a state in which the party does more to steer flows of money, sets tighter parameters for entrepreneurs and investors and their ability to make profits, and exercises even more control over the economy than now.

....Industries that Mr. Xi views as being led astray by a capitalist spirit, including not only tech but also after-school tutoring, digital gaming and entertainment, are bearing the immediate brunt.

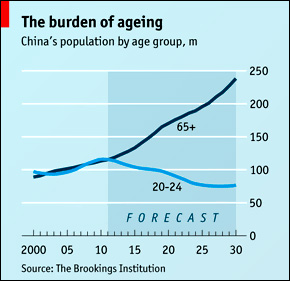

This is not a good sign for China. Free market capitalism may have its problems, but it delivers the goods when it comes to economic growth. Moving even further toward a state-directed economy is almost certain to be a self-destructive move.

It's a funny thing. Back during Cold War 1.0 I felt that right-wingers who hyped the Soviet threat were showing that they didn't have the courage of their economic convictions. The US practiced free market capitalism while the Soviets ran a heavily state-directed socialism. If you really believed in capitalism, you would also have believed that the US would inevitably crush the Soviets and eventually put them into bankruptcy if they tried to keep up (or pretended to).

This is why, aside from the nuclear threat, I was never much worried about the Soviet Union's global ambitions. I did believe in capitalism, and the Soviet Union seemed like a country that would fall further and further behind us until its influence in the world was all but gone.

Now we're stumbling into Cold War 2.0, and China is certainly a bigger economic competitor than the old Soviets ever were. Nevertheless, I still believe in capitalism. China is far behind us economically, and if they're actively backing away from free markets they're unlikely to ever make up the gap.

And that's not all. I'm no China expert, but I've long thought that China is likely to reach a point this decade where they start to have real challenges from both demographic decline and a difficult transition away from a low-wage economy. If they also choose this decade to strangle their economy their problems will only multiply.

And that's not all. I'm no China expert, but I've long thought that China is likely to reach a point this decade where they start to have real challenges from both demographic decline and a difficult transition away from a low-wage economy. If they also choose this decade to strangle their economy their problems will only multiply.

I'm all in favor of keeping of keeping a gimlet eye on China. Our plan of engaging with them in hopes that they'd become a better actor on the world stage obviously didn't work, and over the last few years it's become increasingly obvious that they consider us their #1 adversary. That said, it would be wise on our part not to overestimate their capabilities or to panic every time they launch a new aircraft carrier. If the Journal is right about their economic direction, we will simply outgrow them, just as we outgrew the Soviet Union.

Have faith in capitalism, China hawks!

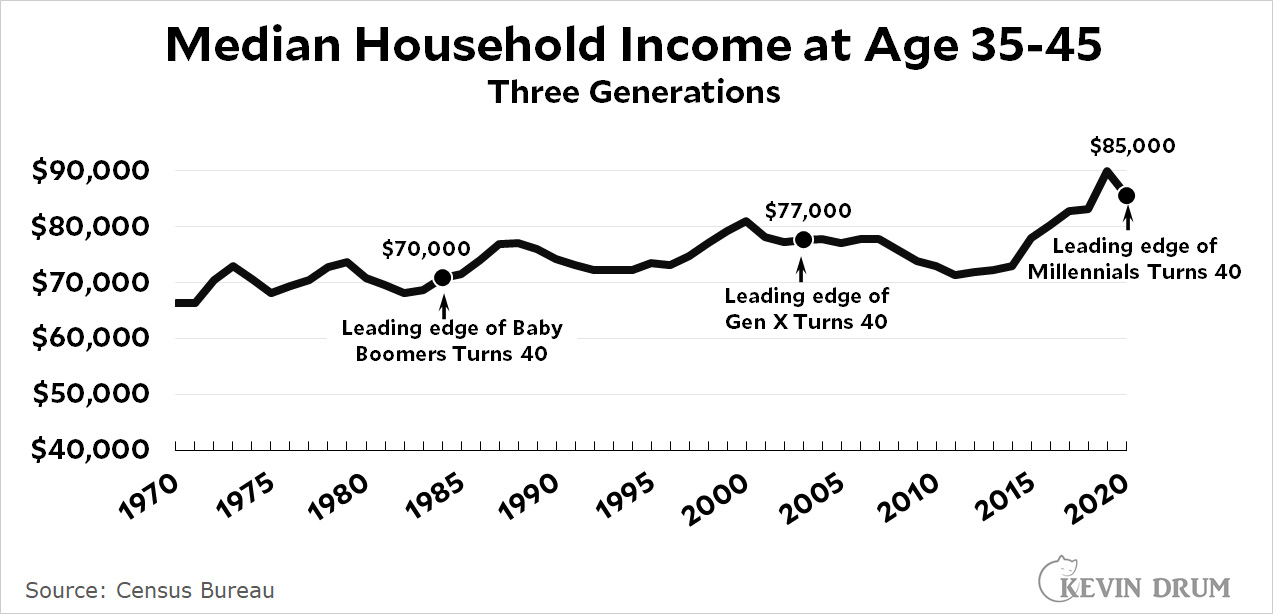

I happened to click today on a post about the (still) massive power of the Baby Boomer generation, something about which I'm fairly agnostic. However, before I even got to the main argument I ran across this throwaway line:

The American Dream is no longer true in the way it was for more than a hundred years: the average Millennial will earn less money than their parents.

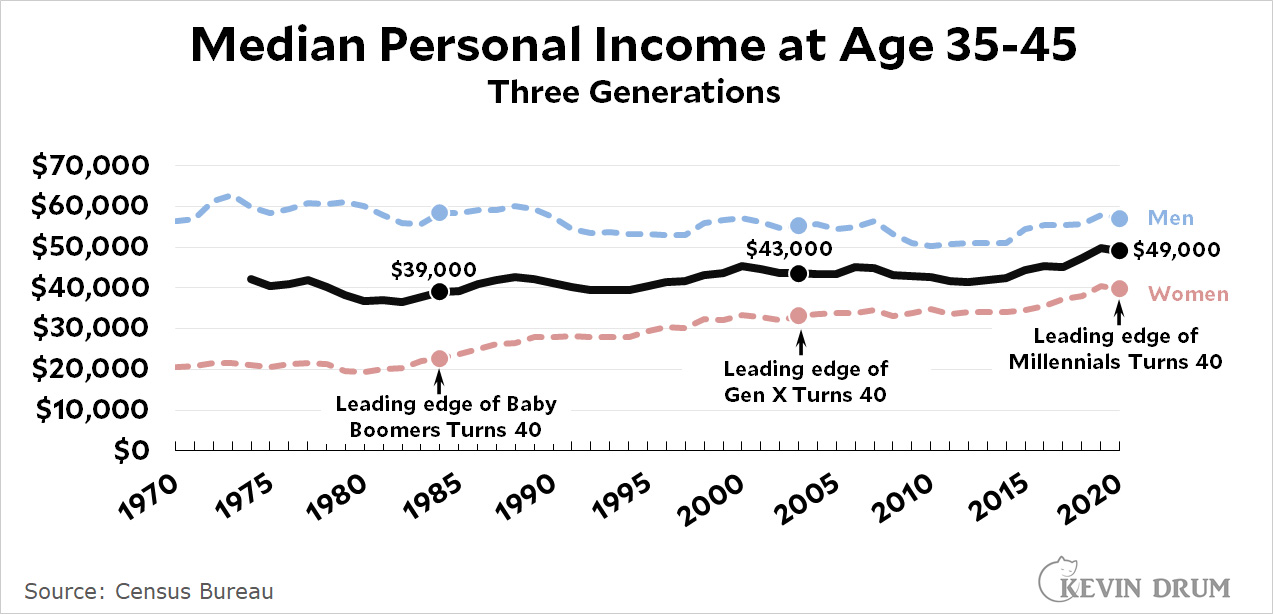

This is yet another example of conventional wisdom that gets repeated forever even when recent evidence tells us it's no longer true. Here is household income at age 35-44 for Boomers, Gen X, and Millennials:

Millennials at age ~40 earn quite a bit more than Boomers did at age 40. This is median income adjusted for inflation, so it doesn't include zillionaires and it's real dollars.

But wait. Household income may have gone up because there are more two-earner families than in the past. That's true, so let's look at individual income:

Averaged together, Millennial income at age 40 is about 25% higher than Boomers at the same age, but the earnings of men have been basically flat while the earnings of women have gone up 75%. In other words, individual earnings of Millennials at age 40 are quite a bit higher than Boomers at age 40, but the distribution of those earnings is quite different.

There are technical details here about age distribution within the 35-44 band and a few other things, but nothing that makes more than a small difference. And you can always cherry pick the data to show anything you want. But if you just look at straightforward income figures, Millennials earn more than comparable Gen X and Boomer workers.

So what accounts for the ongoing myth of Millennials being worse off than Boomers? My guess is that lots of people simply refuse to acknowledge what's happened in recent years. In 2012 you could make a case that Millennials were indeed a lost generation, and it quickly became received wisdom that this was true. But starting in 2015 incomes began a powerful run, increasing by nearly a quarter before dropping a bit during the pandemic year of 2020.

In other words, the Great Recession hit Millennials hard, but it was a temporary hit and Millennials enjoyed strong income gains during the recovery. They are now the highest paid generation in American history, but only if you look at data going all the way to the present instead of just chopping things off at 2012 and never looking again.

Every year I take a picture of a local rabbit. Usually it's a rabbit hopping around my neighborhood, but this year it's a rabbit in the far wilds of Laguna Beach. So here it is: the 2021 Rabbit of the Year.

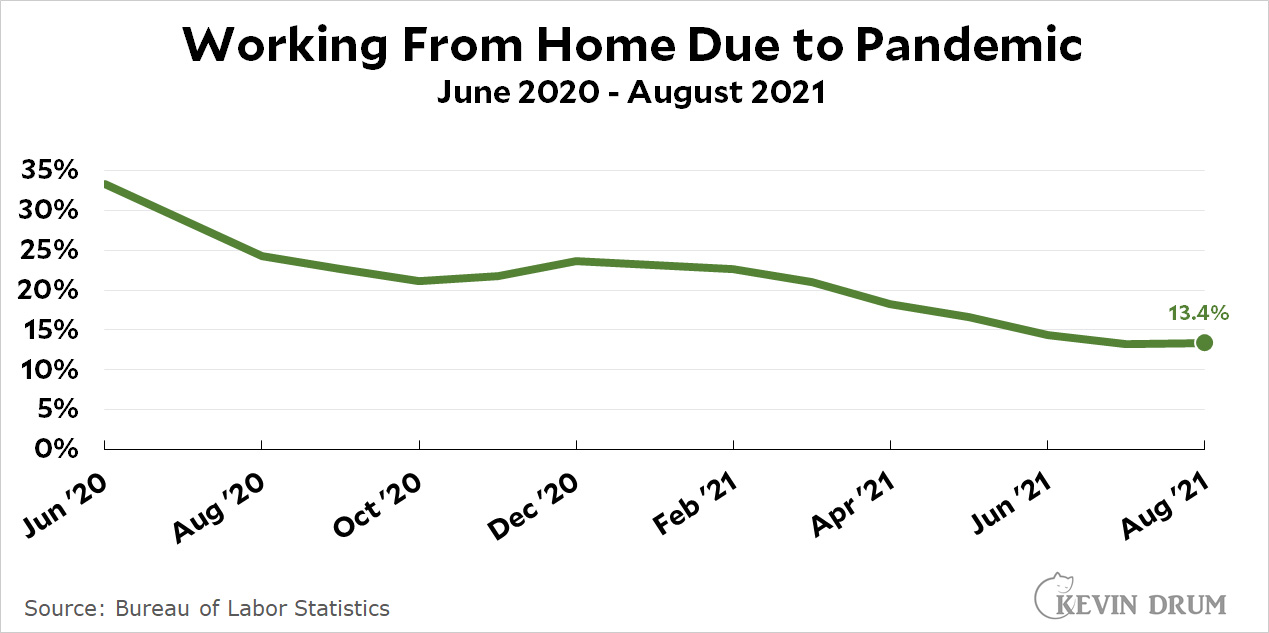

Here's some raw data for the "COVID-19 changed everything forever" file:

I was inspired to retrieve this data by a short piece in the Atlantic that points out just how badly we smart people have estimated the impact of the pandemic:

Last week, The Atlantic commissioned a poll from Leger, asking Americans to estimate how many people had worked from home during the pandemic....About 90 percent of surveyed respondents who worked from home in August because of the pandemic guessed that at least 40 percent of Americans did too. In reality, only 13.4 percent worked from home in the final month of summer.

There are two fundamental disconnects here. First, white-collar folks routinely forget that the vast majority of jobs—nurses, truck drivers, retail clerks, etc.—can't be done from home in the first place. Only about a third of all jobs are even open to telecommuting.

Second, white-collar folks sort of assume that everyone is like them. If they've been telecommuting, or if they know others who have been telecommuting, then it seems natural that loads of people are telecommuting. But it's not so.

Anyway, we're already down to a pandemic-related telecommuting rate of 13% and the trend is still going down. This isn't proof of anything, but it's certainly suggestive that a year from now the overall rate of working from home will be a little higher than it used to be, but will hardly represent a massive upheaval in the workplace.

Always remember Kevin's Law of the Pandemic: When it's over, everything will go back to normal. People claiming that it will spur a permanent change in _________ are pretty much all wrong.

Ezra Klein reminds me today of a report from the Niskanen Center that got some attention a week ago. Here is its core claim:

We are in an era of spiraling costs for core social goods — health care, housing, education, child care — which has made proposals to socialize those costs enormously compelling for many on the progressive left.

This is something that seems so obvious the authors barely even felt like they needed to back it up. But costs aren't spiraling for these things. In fact, costs in these four categories range from basically flat to "it's complicated." Here they are one by one.

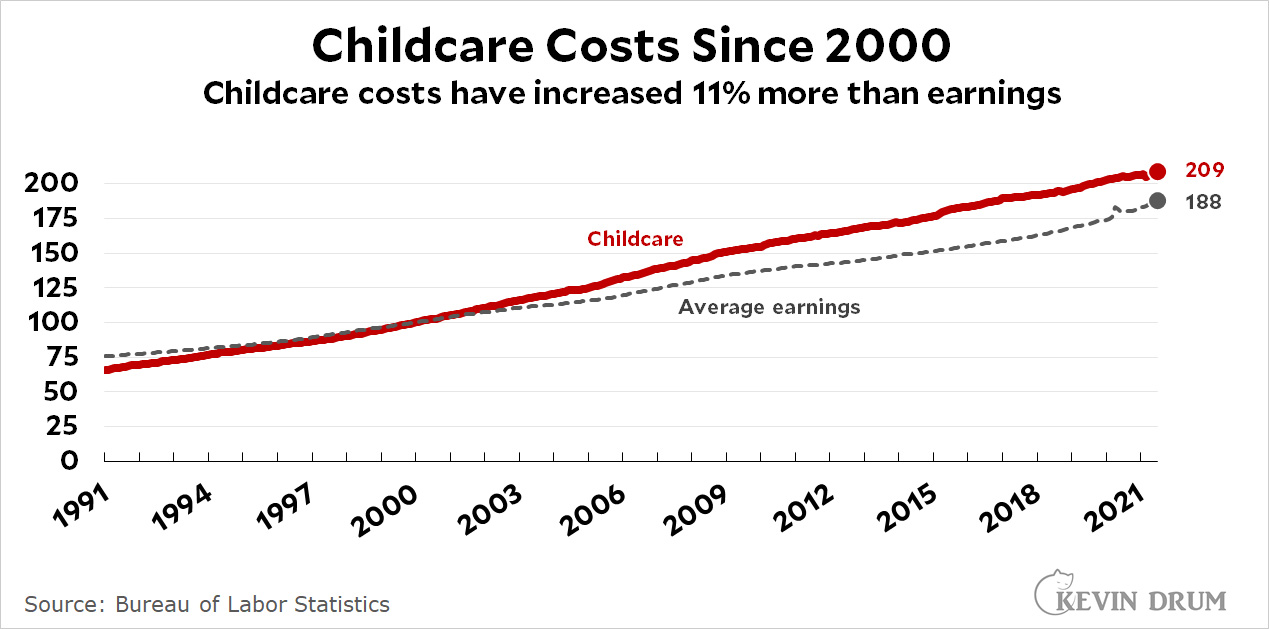

The Bureau of Labor Statistics has always tracked childcare inflation as a separate category—though for some reason this seems to be a closely guarded secret or something since you hardly ever see it. Here it is using 2000 as a starting point:

Childcare costs have risen about 11% more than average earnings. That is an increase, but it's hardly "spiraling."

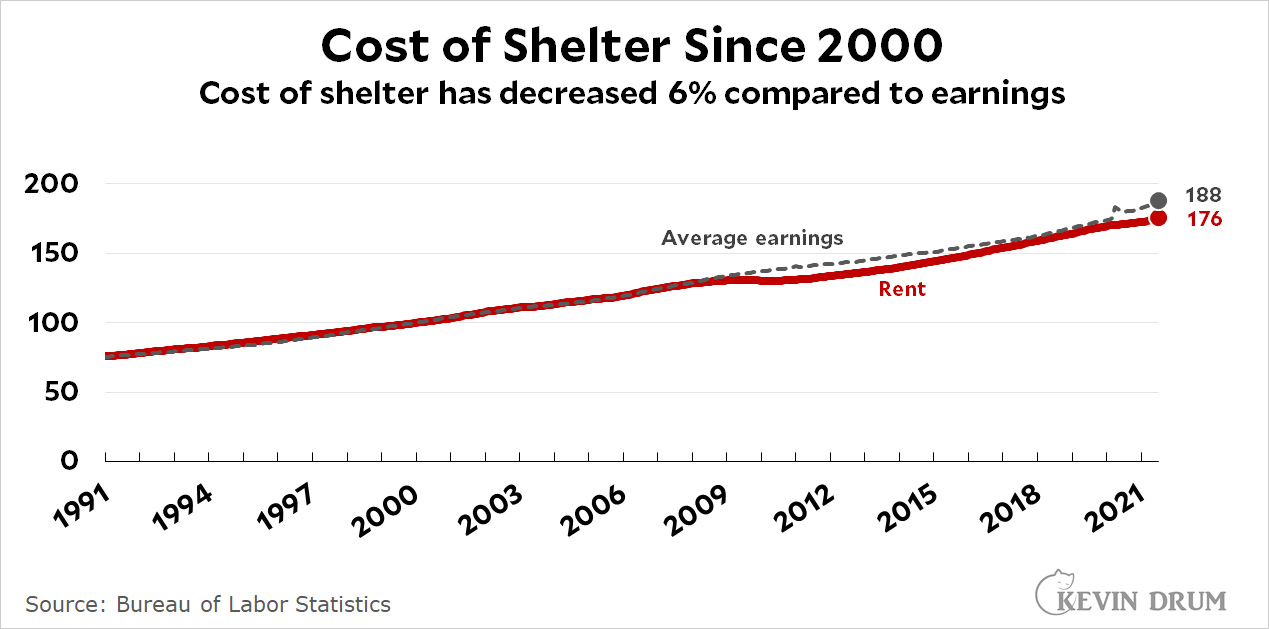

We've been though this before, but here it is again:

The cost of housing has gone up less than average earnings. If you were to account for lower interest rates, you'd find that mortgage payments have risen even less.

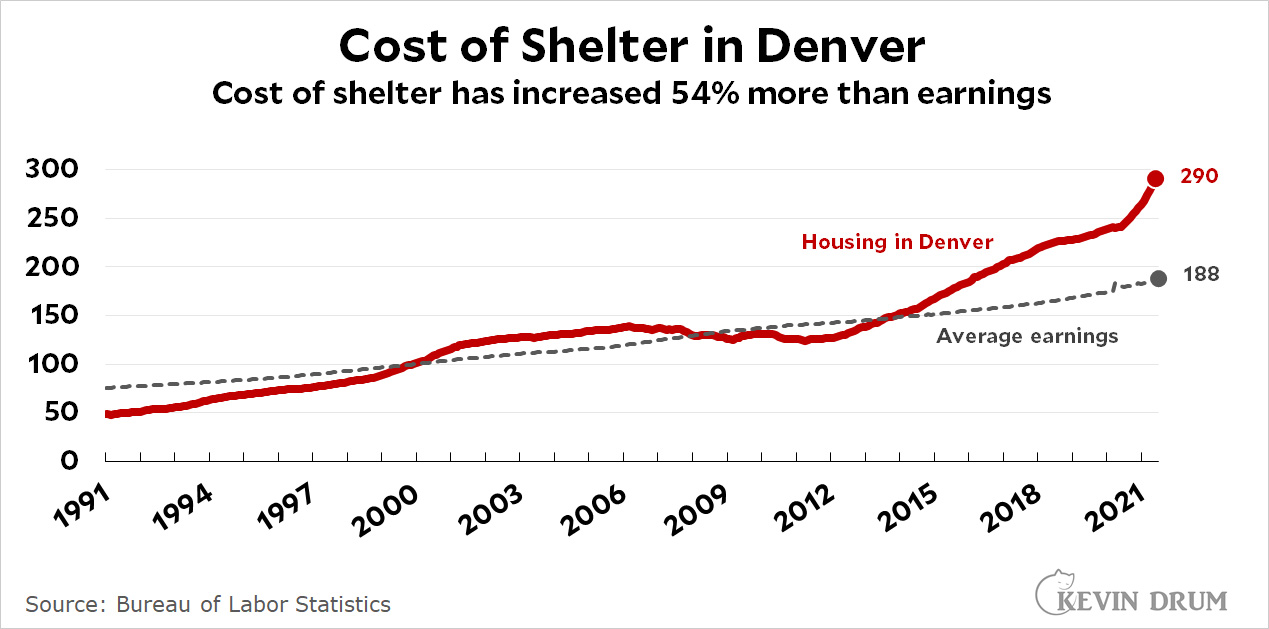

As always, however, there are exceptions. There are always trendy markets that skyrocket for a while before giving way to the newest trendy market. For example, here is Denver:

On average, the cost of housing has been pretty stable over the past 20 years. But it's a bell curve, and there are always going to be cities on both the high and low side.

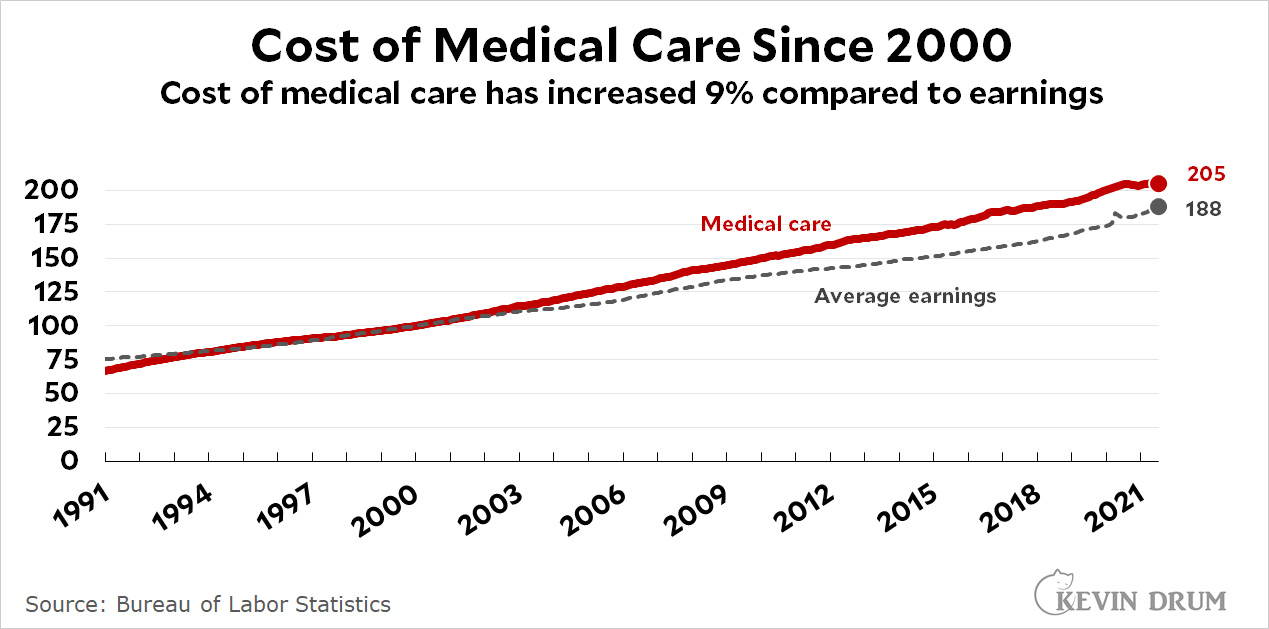

Now we're getting into "it's complicated" territory. The basic story of healthcare costs is that they skyrocketed in the 80s and 90s, but have flattened out over the past couple of decades:

This is a very well known trend among people who actually follow healthcare costs. Medical inflation is still a bit higher than overall inflation, but not by a lot. It turns out that the 80s and 90s were an aberration, and we've since returned to the lower healthcare cost growth of earlier years.

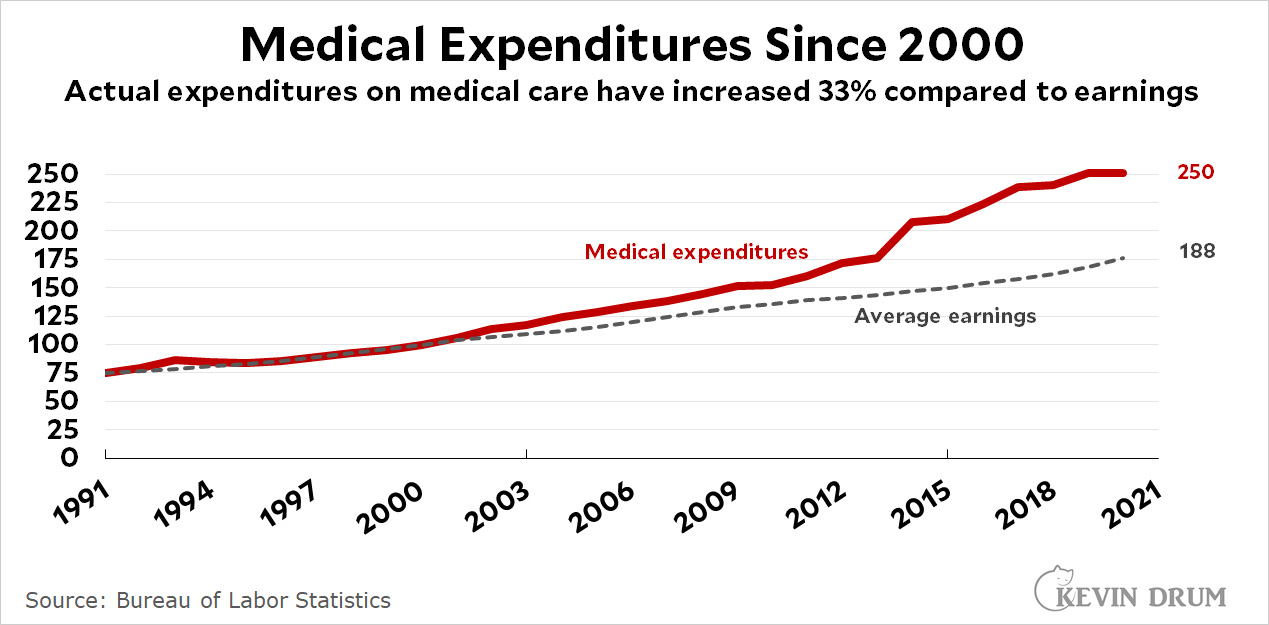

But that's not the whole story. Here are actual consumer expenditures on healthcare:

What's going on here? If medical inflation is restrained, why are we paying way more for healthcare than we used to?

The answer is that consumers are paying an increasing share of healthcare costs. Employer healthcare programs are charging bigger and bigger premiums for policies that have larger deductibles and higher out-of-pocket maximums.

There's no question that this trend is driving public sentiment toward subsidized and/or national healthcare. However, it's important to understand the underlying cause. It's not that medical care costs are spiraling, and if that's your target you're missing what's really going on.

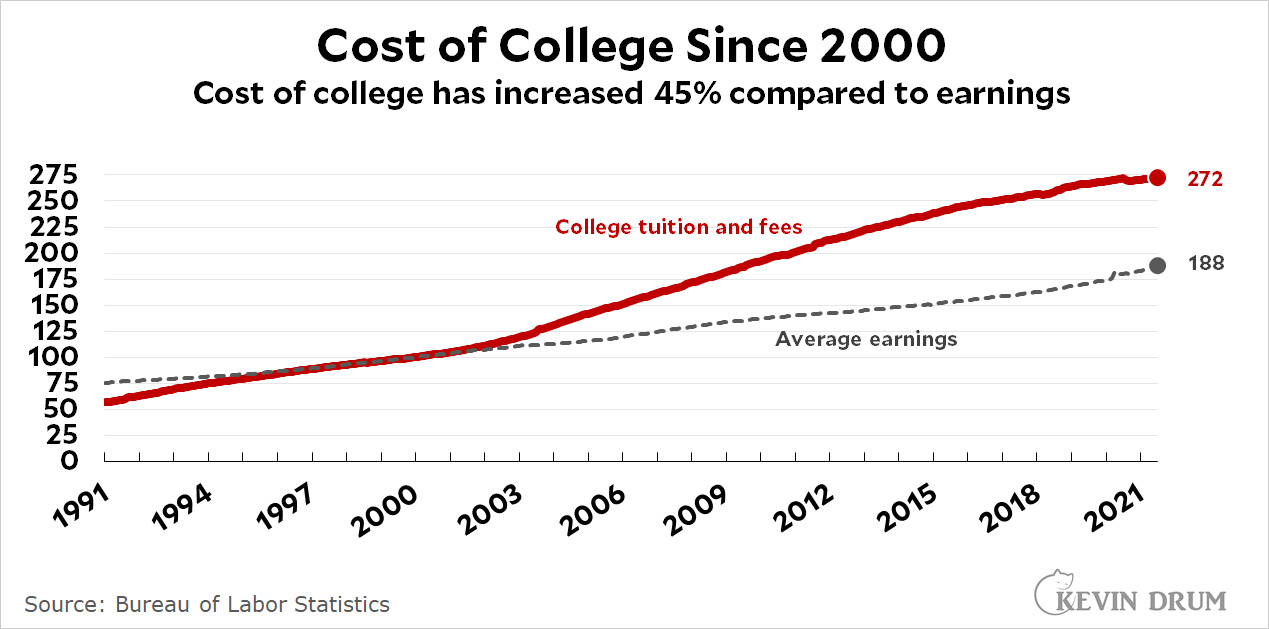

Finally we get to something where costs really are spiraling:

Even here, though, "it's complicated" rears its head. For starters, universities are the original masters of price discrimination: in the same way that the person sitting next to you on a plane may have paid double—or half—what you paid, averages mean nothing in higher education. Everyone pays a different price.

In particular, the net cost of tuition and fees for most public universities is basically zero for anyone with a working class income or less, and fairly modest for those with middle-class incomes.

On the other hand, this doesn't include housing, which is high for some but zero for kids who live at home and attend a commuter college.

On the other other hand, costs have spiraled for those with higher family incomes, and that's contributed to the explosion of student debt.

On the other other other hand, the most outrageous stories of student debt come from for-profit trade schools and graduate students (mostly law and MBA students). Student debt is truly a problem even for ordinary 4-year undergrads, but it's mostly a problem for those with decent family incomes and fairly good career expectations.

These are all details, and they're important, but of the four things mentioned by the Niskanen report this is the one that truly does fit their premise. Higher education costs really are spiraling, and that really does push public sentiment in the direction of ever higher subsidies. That's not a sustainable dynamic in the long run.

That's that. But why do I bother with stuff like this? It's because I look around and I see endless evidence of conventional wisdom that never gets questioned even though it's fundamentally wrong. It seems like I and others spend a lot of time pointing out things like this but it just never sinks in.

Don't take any of this as gospel. I may have some things wrong myself. However, I'm pretty sure I have the big picture mostly right, though it never seems to make much of a dent in public discourse.

Want more examples? A lot more? There's always this.

The Senate parliamentarian has once again handed down a ruling that irks progressives, and as usual progressive Twitter is outraged. Why does an unelected bureaucrat get to make these decisions? Chuck Schumer should fire her. The president of the Senate should overrule her.

This is so stupid and so tedious. Every legislative body has a parliamentarian. Her job is not to make the rules, only to enforce them. In this case it's the Byrd Rule that's up for interpretation, and the Byrd Rule says that you can pass legislation in the Senate with 51 votes only if it directly affects the budget. The legislation at hand concerns a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants, and the parliamentary ruling on it was a no-brainer: Its effect on the budget is plainly incidental to its primary purpose. This means Republicans can filibuster it, which in turn means it needs 60 votes to pass.

This was never seriously in question and has nothing to do with the parliamentarian. Anyone would have handed down the same ruling.

So what about just firing her or overruling her? Sure, you could do this, but it's effectively the same as eliminating the filibuster. You'd be giving the Senate majority leader the ability to block a filibuster anytime he feels like it.

So forget about the parliamentarian. The underlying key to every problem in the Senate is unanimous consent in general and the filibuster in particular. If you want to fix the Senate, getting rid of those things is the only way. But you need 51 votes to do it, and right now Democrats don't have 'em. Until they do, nothing else matters.

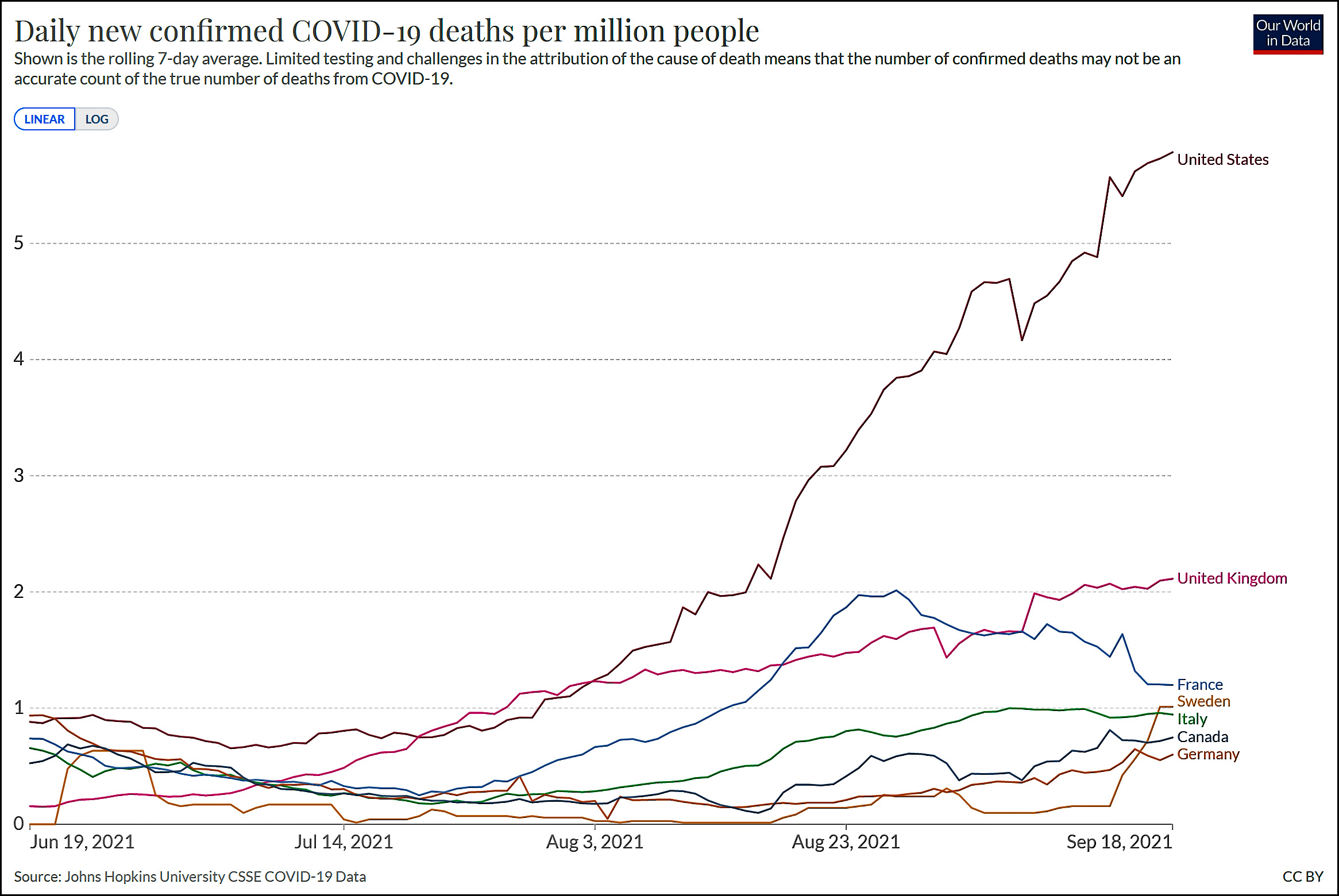

It looks like our mortality rate from COVID-19 is starting to reach its peak. Maybe. I guess that's good news, though this chart is frankly too depressing to think that anything in it represents good news.