A few days ago the Washington Post ran a piece about the Great Resignation that focused on Hinesville, Georgia. It was based on extensive interviewing that tried to get to the bottom of how the GR was hurting Hinesville businesses and the community in general. However, it left me puzzled. Once you plow carefully through everything, it turns out there are basically three problems.

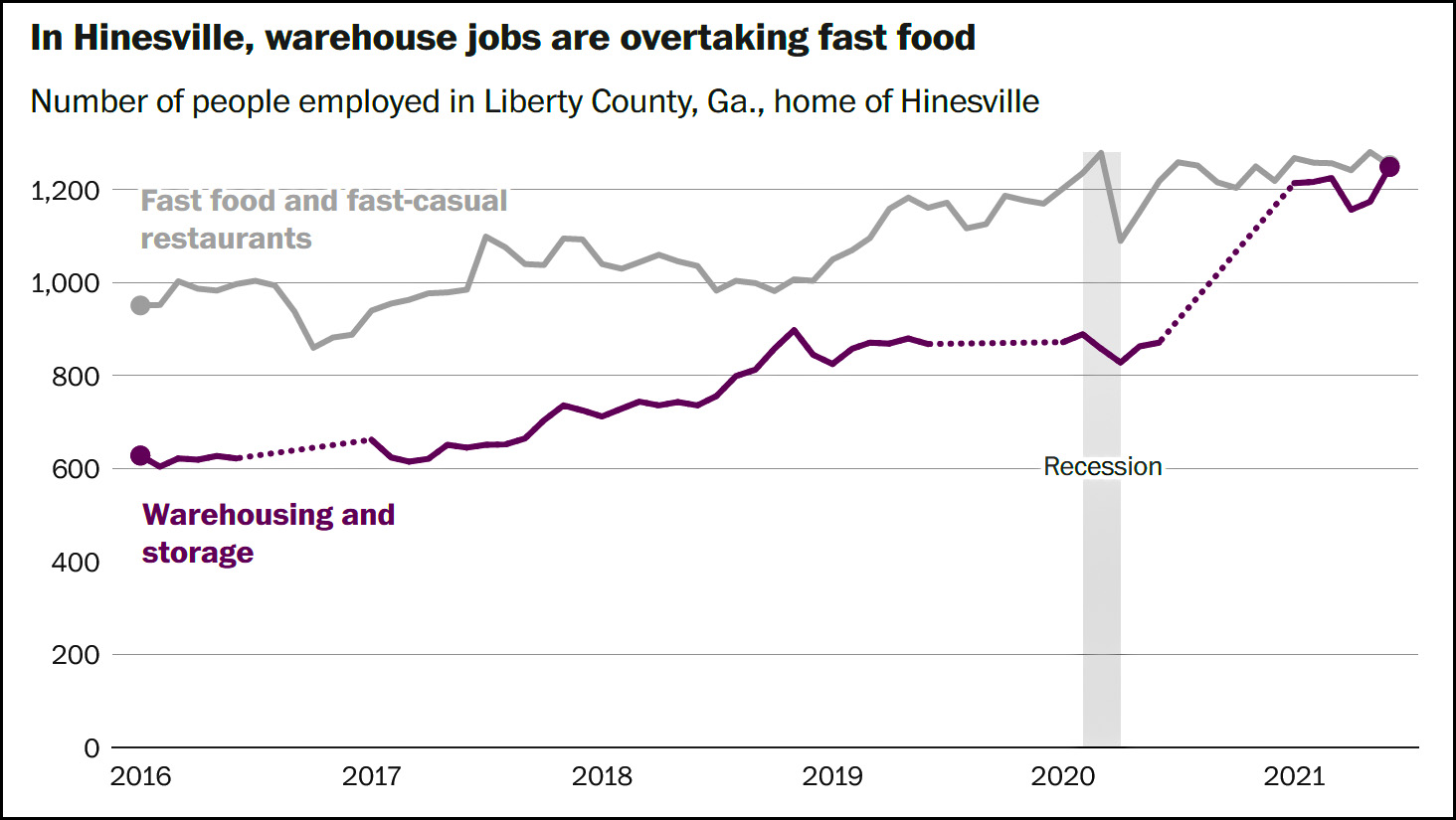

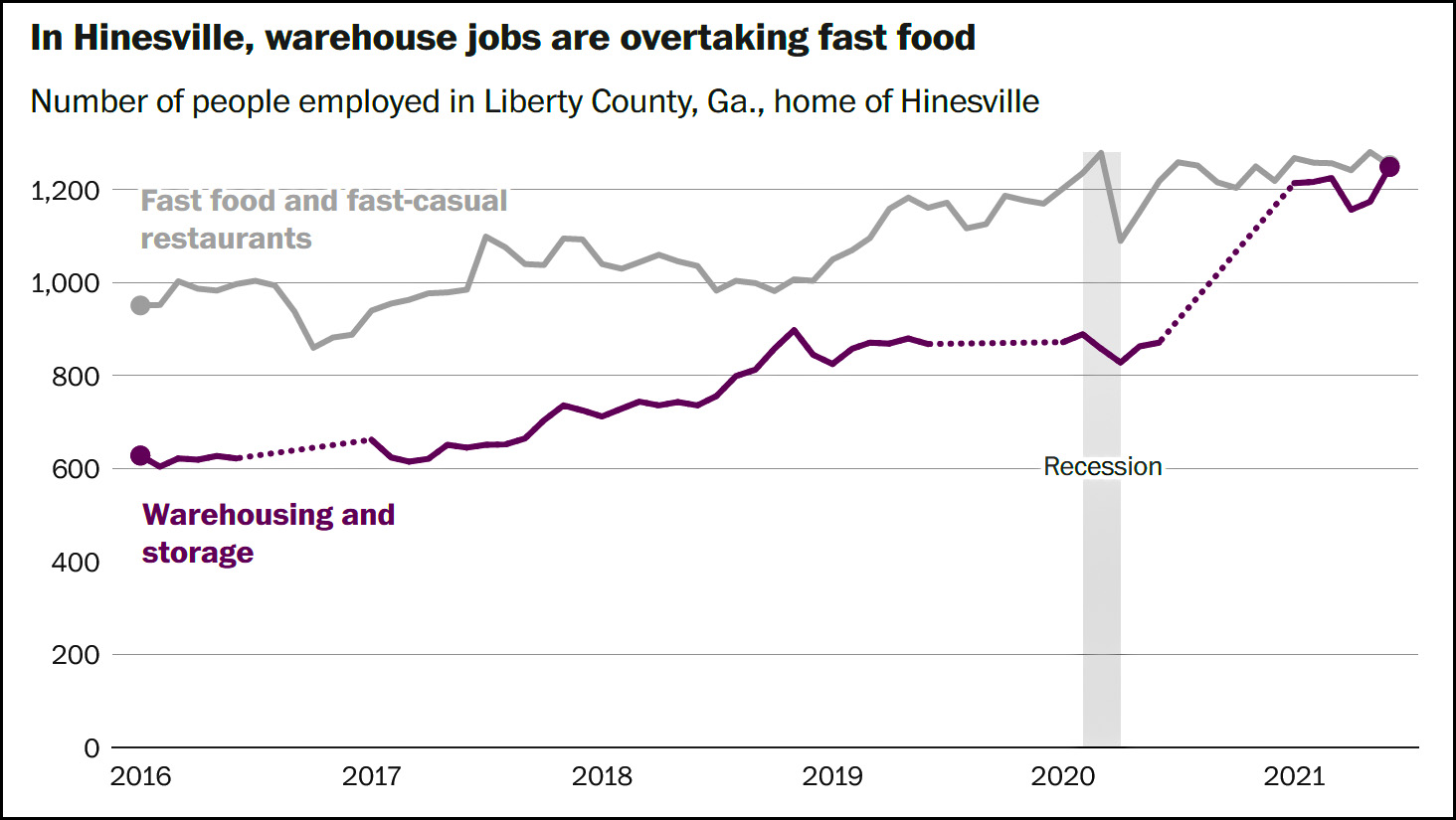

First off, Hinesville has seen a big increase in good-paying warehouse jobs, so people have been leaving crummy minimum wage jobs to go work in a warehouse. But this started at least five years ago and has been ongoing ever since. It has nothing to do with the pandemic.

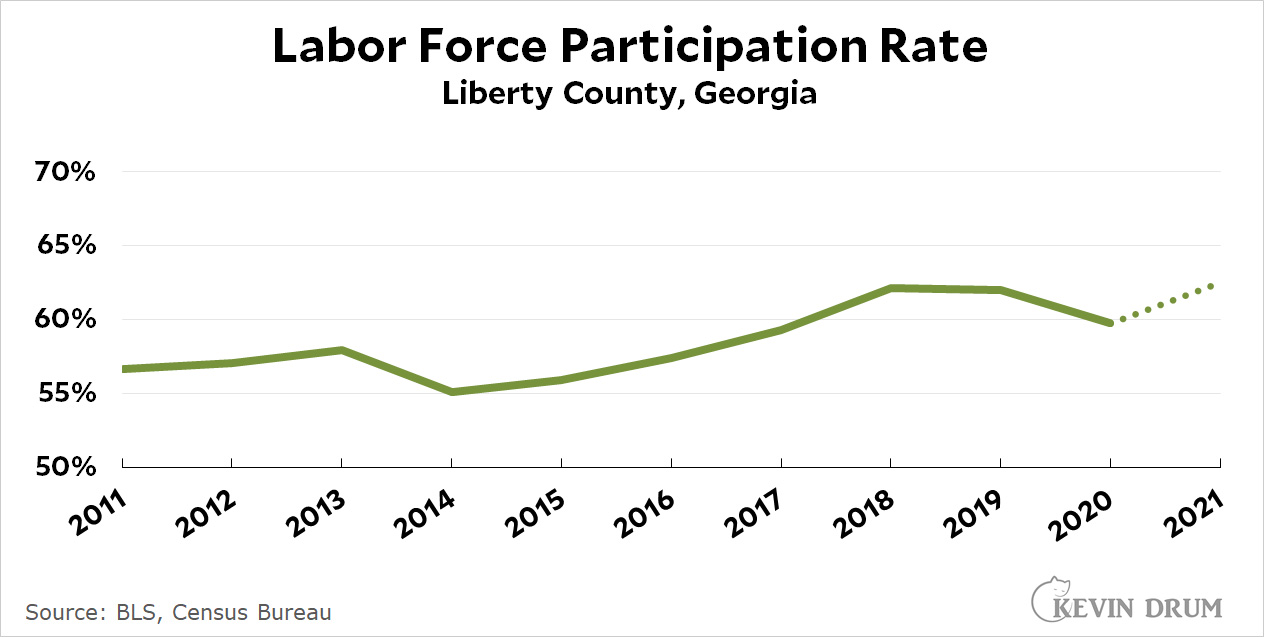

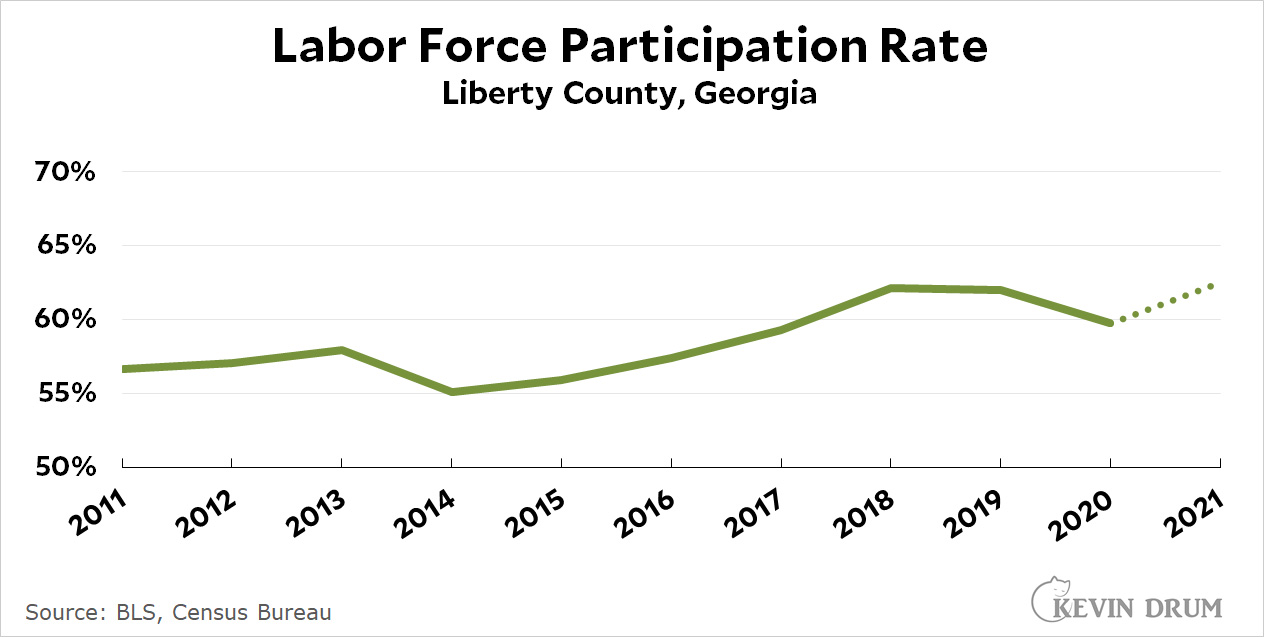

Second, some people—it's unclear how many—have decided to leave the workforce and subsist on government benefits. However, as time goes by and savings dry up, more and more of them are returning to work. If my arithmetic is correct, practically all of them have returned by now:

As of October, the participation rate in Liberty County is the highest it's been in the past decade. There's hardly anyone staying home just to collect government bennies. (At least, no more than usual.)

As of October, the participation rate in Liberty County is the highest it's been in the past decade. There's hardly anyone staying home just to collect government bennies. (At least, no more than usual.)

Finally, there are supposedly a lot of people who quit working at restaurants during the pandemic and have never come back. But that's entirely contrary to this chart:

If this is accurate, employment in restaurants has been growing for years. It fell a small bit at the start of the pandemic, but then rebounded and has been growing at its usual rate ever since. There's no apparent lack of workers.

If this is accurate, employment in restaurants has been growing for years. It fell a small bit at the start of the pandemic, but then rebounded and has been growing at its usual rate ever since. There's no apparent lack of workers.

As best I can tell, the only actual problem in Hinesville is that "mom and pop" restaurants say they can't afford to raise wages the way national fast food franchises can. But this is never explained. If a local McDonald's can afford to raise its wages, why can't a local pizza joint? They both have similar cost structures and they're both competing for the same customers. And local franchises are on their own, just like the mom-and-pop places. It's not as if the national corporation bails them out if they're losing money.

I don't doubt that everyone quoted in the piece is talking honestly, but the only serious problem seems to be the fact that mom-and-pop shops feel that they can't raise wages enough to attract workers. But is this true? Or could they go ahead and do it because everyone else has to do it too? If everyone has to raise wages, after all, the competitive landscape doesn't change much.

Maybe there's something here I'm missing. But one thing is for sure: all the problems supposedly related to the Great Resignation just don't pan out. Whatever problems Hinesville is suffering, they have entirely different sources.