Ezra Klein wrote this weekend about a new study that tries to figure out why some countries did better with COVID-19 than others. Since COVID affects older people more severely than younger people, countries with older populations generally had more COVID deaths than younger countries. That was it. Nothing else had much predictive power.

But what about infection rates?

More unexpected was what the researchers found when they looked at the factors that predicted how many people got infected. Some of the obvious candidates — population density, G.D.P. per capita, and exposure to past coronaviruses — failed to predict much in the way of outcomes. But both trust in government and trust in fellow citizens proved potent.

....This yields the paper’s most striking finding: Moving every country up to the 75th percentile in trust in government — that’s where Denmark sits — would have prevented 13 percent of global infections. Moving every country to the 75th percentile of trust in their fellow citizens — roughly South Korea’s level — would have prevented 40 percent of global infections.

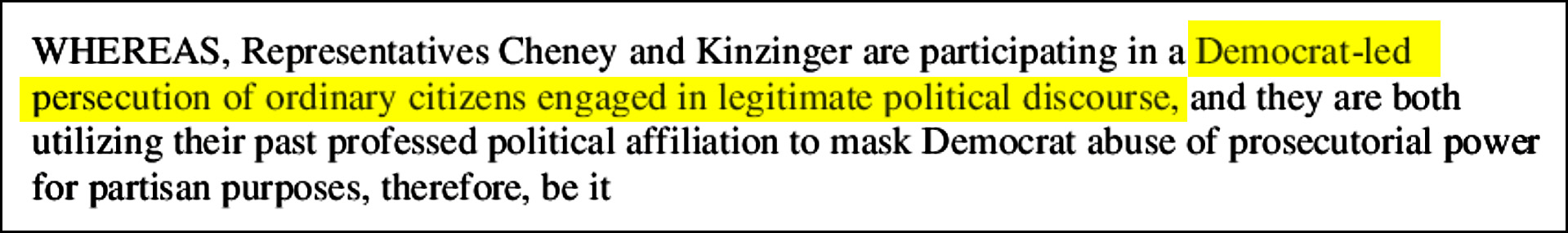

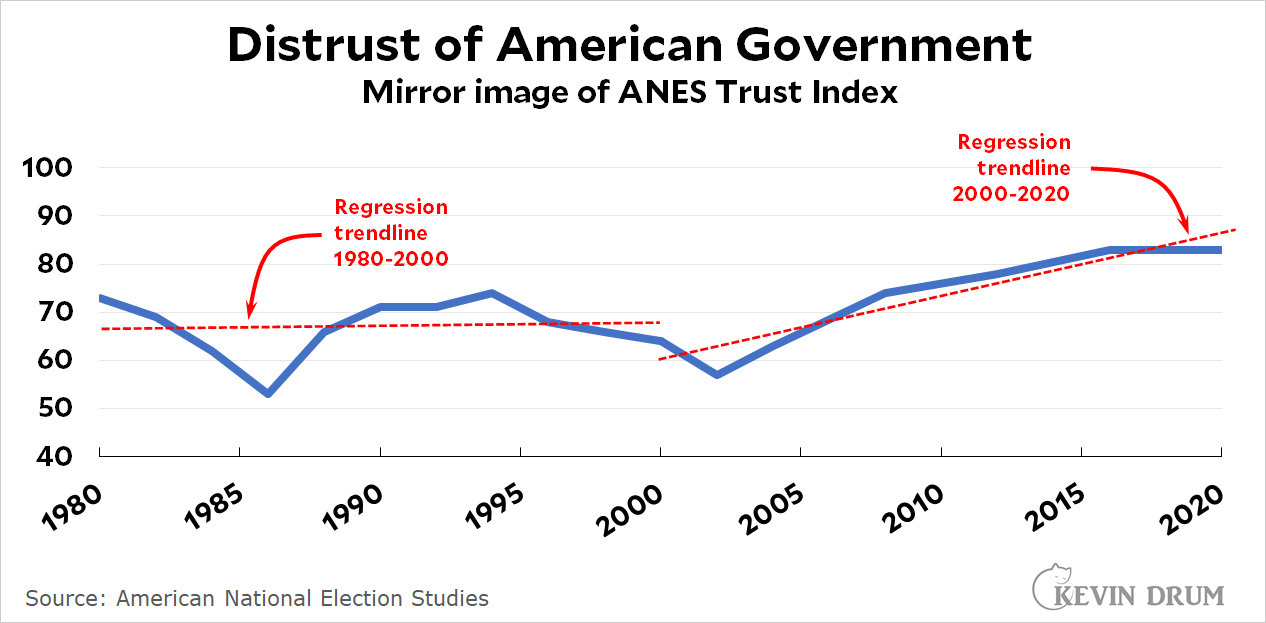

Here is distrust of government in the United States:

Running a simple regression shows that despite the ups and downs, distrust of government changed little between 1980 and 2000. But since 2000 it's soared.

Running a simple regression shows that despite the ups and downs, distrust of government changed little between 1980 and 2000. But since 2000 it's soared.

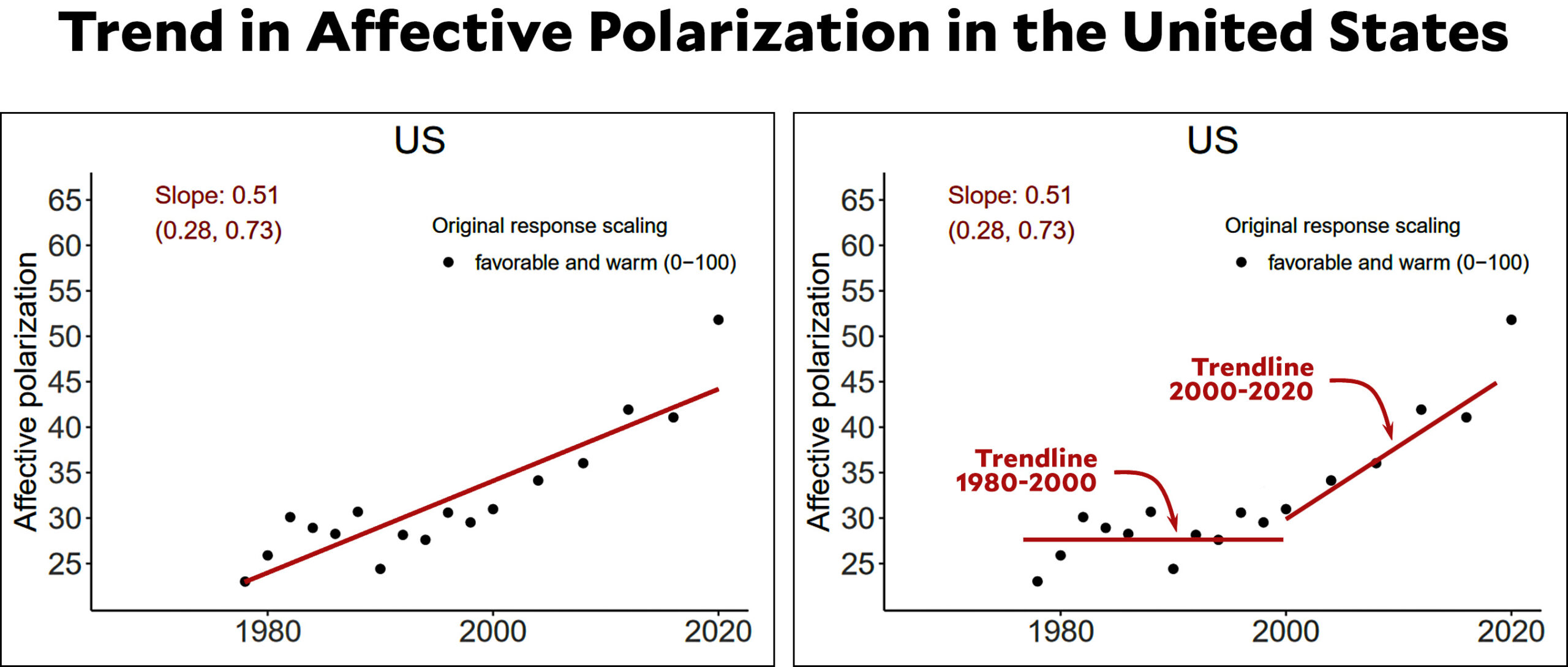

Next up is something called affective polarization. Roughly speaking, this is how negatively you feel toward the opposite political party. Here are the results from a recent study:

The authors rammed a linear regression through the data (left chart), as they did for all the countries they studied, but even a brief eyeball examination suggests there's nothing linear about this (right chart). From 1980 through 2000 nothing much changed, but from 2000 through 2020 everybody went crazy. Dislike of the other party skyrocketed more than 50%.

The authors rammed a linear regression through the data (left chart), as they did for all the countries they studied, but even a brief eyeball examination suggests there's nothing linear about this (right chart). From 1980 through 2000 nothing much changed, but from 2000 through 2020 everybody went crazy. Dislike of the other party skyrocketed more than 50%.

In other words, starting around 2000 both distrust of government and our dislike of people in the other party shot up. And if anything explains our lousy response to COVID, even though we were rich and well prepared, that's it.

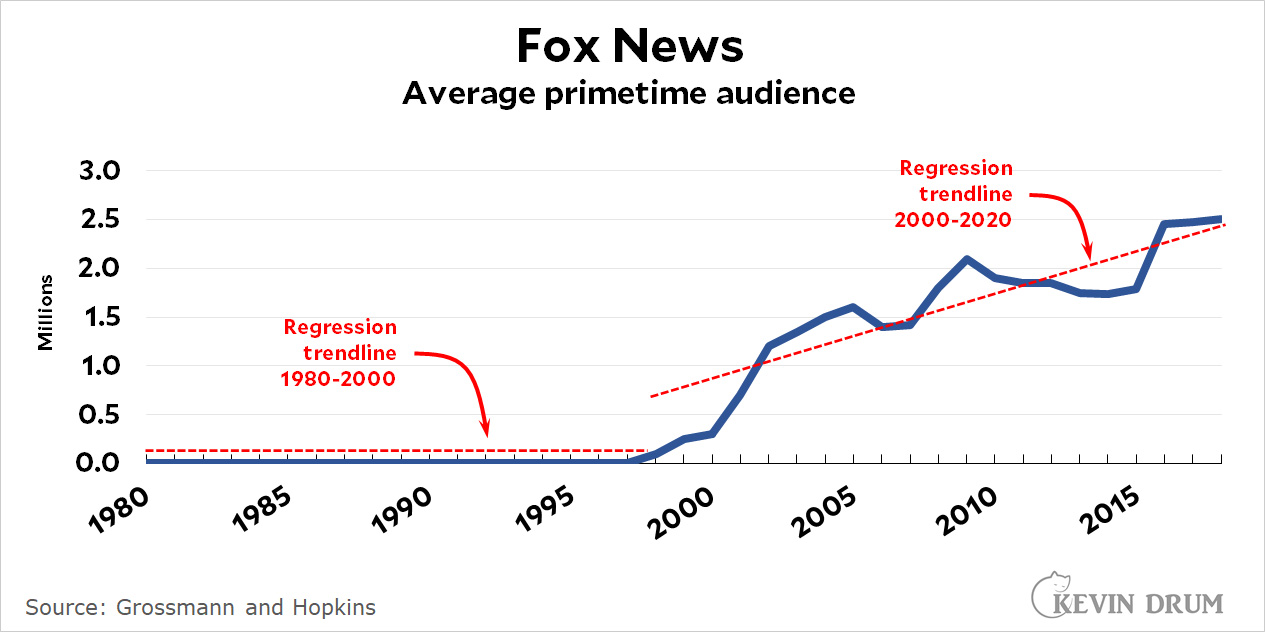

So what happened? I think you all know the answer, but here's one more chart presented in a slightly unusual way. It shows the average primetime audience for Fox News:

Obviously the trendline is flat from 1980-2000 since Fox News didn't even start broadcasting until 1996. But Rush Limbaugh and Newt Gingrich and Matt Drudge had provided fertile ground for explosive growth. Nothing happened for the first few years as Fox struggled to get carried by cable outlets throughout the country, but starting in 2000, with carriage contracts in place, their viewership skyrocketed.

Obviously the trendline is flat from 1980-2000 since Fox News didn't even start broadcasting until 1996. But Rush Limbaugh and Newt Gingrich and Matt Drudge had provided fertile ground for explosive growth. Nothing happened for the first few years as Fox struggled to get carried by cable outlets throughout the country, but starting in 2000, with carriage contracts in place, their viewership skyrocketed.

Correlation is not causation. The year 2000 featured the Florida election debacle and the beginning of the George W. Bush administration, while 2001 featured the start of the war on terror. But Florida faded in people's memories; George Bush practically disappeared in 2009; and the war on terror lost most of its momentum by the end of the aughts. And yet, both distrust of government and dislike of the opposite political party continued to grow.

Only Fox News stayed around this whole time, spewing its toxic blend of white fear, vilification of liberals, and scorn of government. None of those was new, but it was Fox News that weaponized them, packaging them with all the skills and glitz of modern marketing and promoting them relentlessly on ostensible TV news programs. It's been enormously successful, and probably would have been enough to turn conservatives into vaccine skeptics all by itself. But just in case it wasn't, Fox also spent much of 2021 airing an explicit vaccine skepticism to its primed and rabid viewers.

Why? Because it made a lot of money for Rupert Murdoch.