Over the past year I've gotten interested in the steady decline of children's mental health. I haven't looked into it in any depth, though, so I was interested in a survey of the topic by Judith Warner in the Washington Post Magazine yesterday. First off, she takes on the possibility that the crisis is an outgrowth of the COVID-19 pandemic:

That’s an explanation that feels right, particularly if you’re one of the millions of parents trying to balance back-to-normal work expectations with the continued chaos of your school-age children’s lives. It feels especially right if you’re someone whose child, pre-pandemic, seemed basically fine (or fine enough) and then just … wasn’t.

But — as the shrinks say — feelings aren’t facts.

Bottom line: It's not COVID. The pandemic might have made things worse, but this problem has been growing for at least a decade. So how about smartphones and social media?

Theories as to why children’s mental health was so bad pre-covid abound. A prominent subset — popularized most notably by San Diego State psychologist Jean Twenge’s 2017 Atlantic story, “Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?” — blames technology. That theory — regretfully, I’m tempted to add, because it’s one of those ideas that, no matter how wrong, still feel perfectly right — has been extensively refuted.

So it's not down to tech. Here's another guess:

Then there’s the view that part of what we’re seeing is a greater awareness and openness about children’s mental health on the part of a new generation of parents, the first to grow up at a time when it was common for kids to be diagnosed with issues like attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and to come of age in a world where celebrities talked publicly about their struggles with depression or addiction. But most experts feel that this hypothesis doesn’t tell the whole story. Beyond the research evidence, their gut-level take tells them that young people truly have become more anxious and despairing.

So there's more. But what? Warner stops there to tell the rest of her story, which is about politicizing mental health and other topics. In other words, we don't really have a good idea yet of why kids today seem to have much worse mental health problems than previous generations.

FWIW, one of the first things I do when I come across something like this is to see if it's worldwide or mainly an American phenomenon. This is hard to suss out, but a brief survey suggests that it's a problem in Europe too, though possibly not quite as severe. So whatever's causing it, it's something at least moderately universal in rich Western countries.

But what?

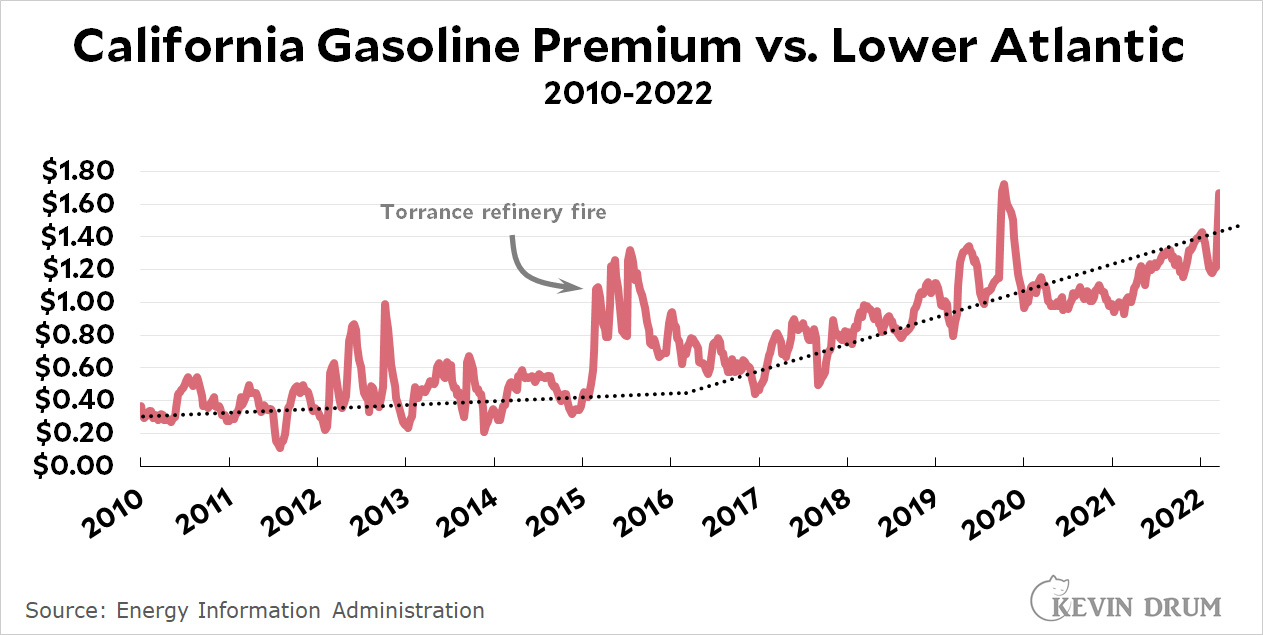

When I last checked in on this in 2019, the California premium was a little over a dollar. Three years later it's continued rising and is now about $1.40, with a recent spike to $1.70.

When I last checked in on this in 2019, the California premium was a little over a dollar. Three years later it's continued rising and is now about $1.40, with a recent spike to $1.70.