Marissa Evans writes about her 70-year-old father's death in January from COVID-19:

Since my father’s death, I have stared at the January 2022 calendar page attempting to trace his COVID-19 exposure and when he started coughing. I’ve tried reconstructing timelines and symptoms with dates, texts and calls to understand why my father died. But I know it will not make sense. The way we lose Black men in America never makes sense.

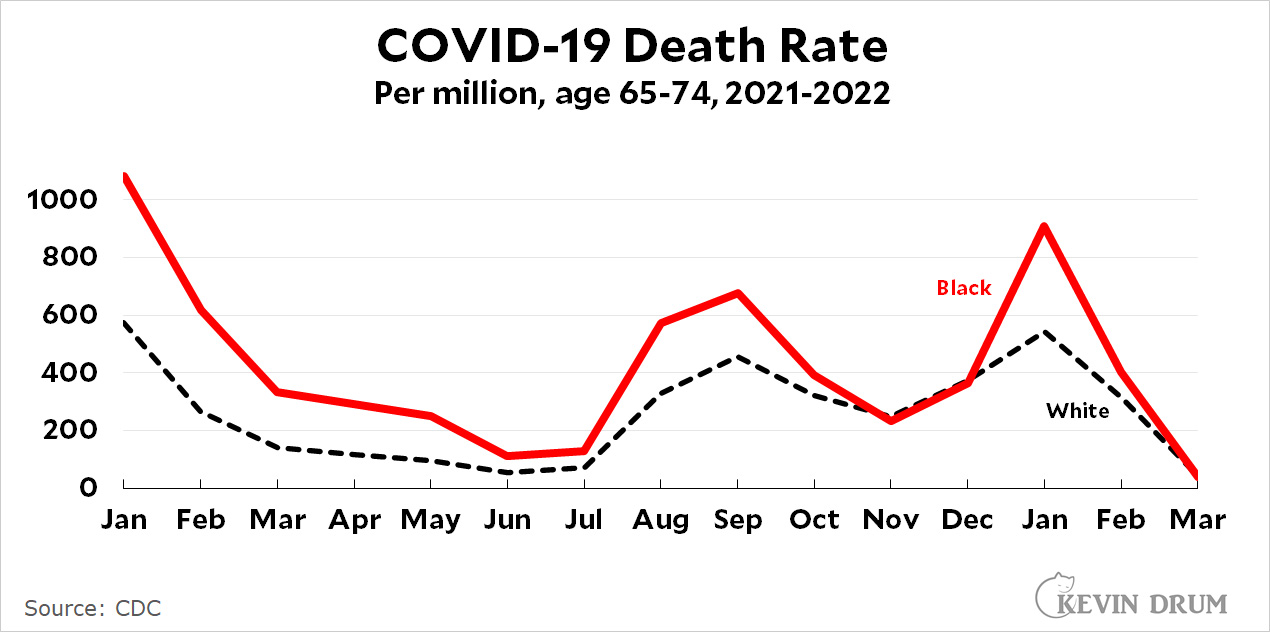

Loving a Black man in America often means your time with them will always seem short-lived....Black people are 2.5 times more likely to be hospitalized and 1.7 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than white people, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

I don't want to reduce Evans's grief to statistics, but COVID death rates actually illuminate—or perhaps add to—her confusion:

There are two obvious things to say here. The first is that although it was once true that the Black community had a higher risk than the white community of dying from COVID, that risk started to plummet in October and has mostly matched the white death rate since then.

There are two obvious things to say here. The first is that although it was once true that the Black community had a higher risk than the white community of dying from COVID, that risk started to plummet in October and has mostly matched the white death rate since then.

But the second thing is that mostly is not always: There was a huge spike in the Black death rate in January—exactly the month that Evans's father died. This was true of all age groups, not just the elderly, and it was outsized compared to both the white and Hispanic death rates. This really doesn't make sense.

When I read pieces like this, which discuss the way Black patients are treated by the medical system, I almost always come away with conflicting responses. On the one hand, I get annoyed at the errors and hyperbole. Generally speaking, Black people aren't dying from COVID at higher rates than white people these days. That's outdated. The PNAS study Evans mentions later doesn't show that lots of white medical students hold outrageous racial beliefs. It shows that when they start school, white students average about 15% incorrect beliefs and this declines to 5% by the end of medical school. Finally, the litany of complaints about various unhappy interactions with doctors rarely strike me as unusual. Doctors periodically treat everyone badly, and most of the complaints feel very familiar to me.

On the other hand, both anecdotes and data really do support the notion that white doctors systemically treat Black patients worse than white patients. Some of this may be class bias more than racial bias, and some of the outcomes are due mostly to problems outside the health care system. (For example, Evans talks about life expectancy, but if you account for income something like 70-80% of the racial difference in life expectancy goes away.) Still, even with all that acknowledged, a racial component always remains. There's just no doubt that, one way or another, the mere fact of being Black leads to worse medical care on average.