Over the weekend Vox published about the millionth article informing us that our response to monkeypox is a total clusterfuck and bears an uncanny resemblance to our infamous COVID-19 clusterfuck.

Sure. Maybe. Generally speaking, though, I sometimes wonder how fast these newly-minted critics think a country should be able to roll out a massive testing and vaccine program for a new disease. But they never say. Nor do they ever hint at any real expertise in ground-level epidemiology and the obstacles it presents. The answers are just a vague faster and we're the richest country in the world for god's sake.

So here's the Vox piece:

Accurate data is critical for public health, and the US doesn’t have it. The US declared monkeypox a public health emergency this month, but the decision may have come too late....Reliable demographic information is key to making the right choices for allocating limited tests and vaccines.

All of this feels like an uncanny echo of the early mishandling of Covid-19....Reporting lags on rising cases meant that lockdowns began too late to save tens of thousands of lives. Similarly, certain communities uniquely at risk, like Black and Hispanic people who lacked access to health care, were suffering higher rates of severe illness and death from Covid before policymakers had any way of knowing where to direct public health outreach.

....The delays and poor coordination between clinics and city health departments meant that contact tracing happened too late to contain the spread. If the spread had been caught earlier, patients would have been more likely to minimize their risk and seek out testing and treatment if they were exposed, and there would have been more advance warning on ordering a vaccine supply.

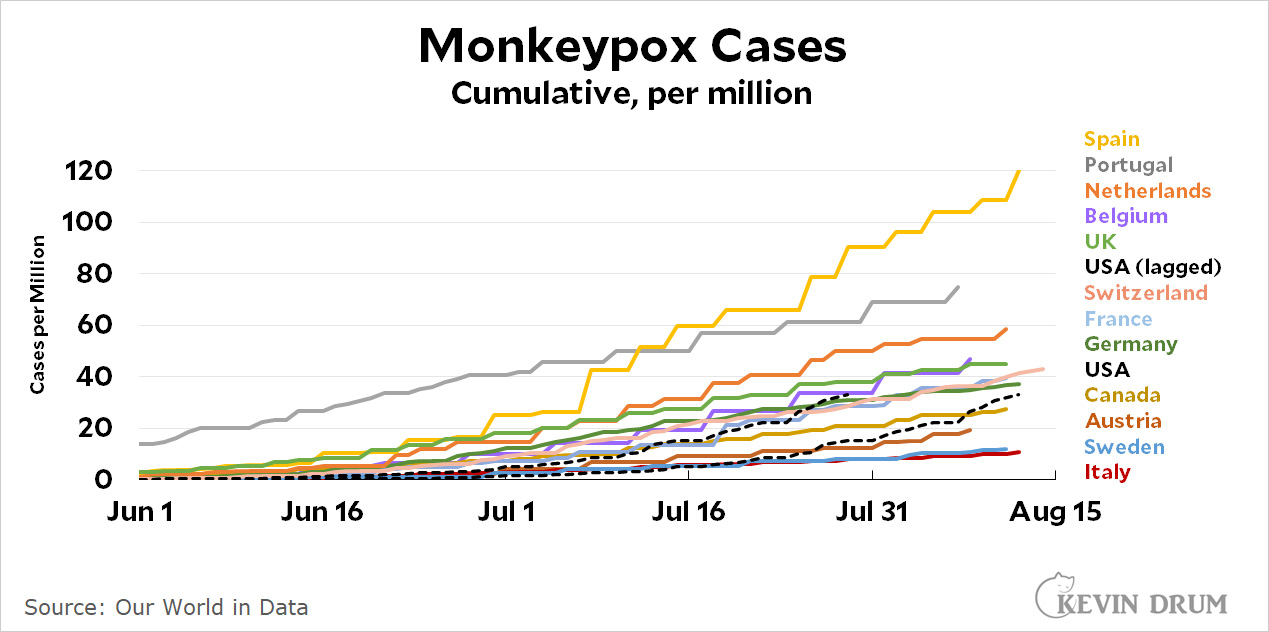

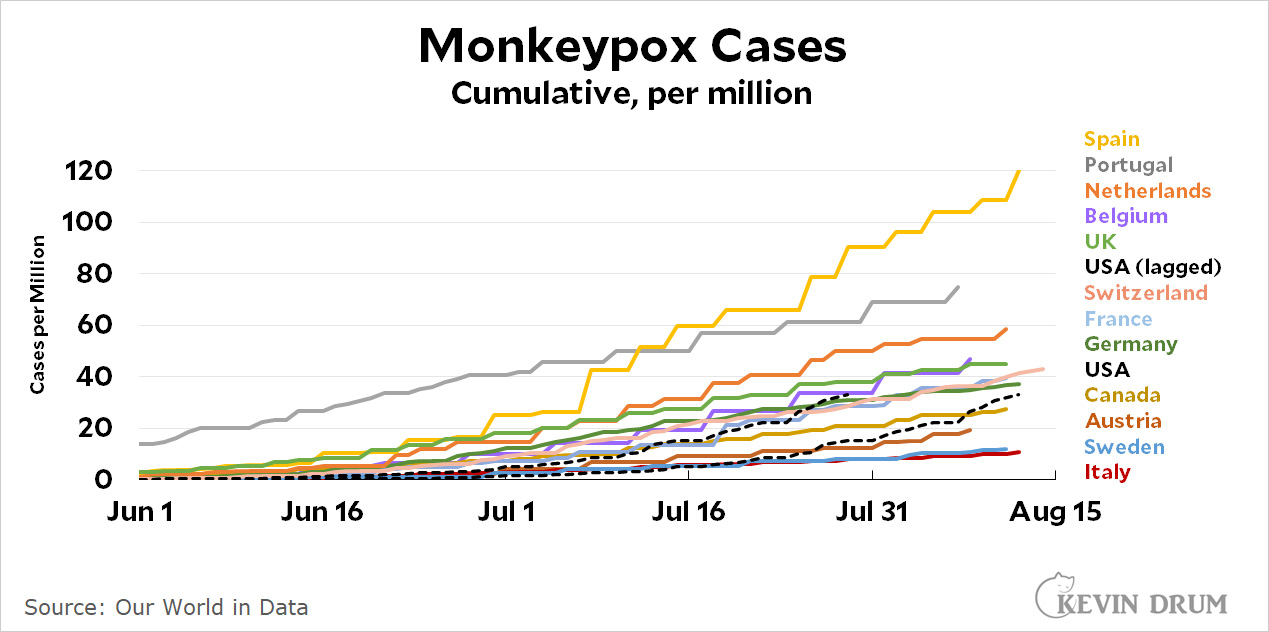

First off, here are the numbers:

You'll notice that there are two lines for the United States. The bottom one is just the normal raw data. The top one is lagged by two weeks to account for the fact that our first case showed up about two weeks after the first case in Europe. I am doing this out of a monumental abundance of fairness.

You'll notice that there are two lines for the United States. The bottom one is just the normal raw data. The top one is lagged by two weeks to account for the fact that our first case showed up about two weeks after the first case in Europe. I am doing this out of a monumental abundance of fairness.

But even using the lagged figure, the US is roughly in the middle of the pack. If our response was terrible, then just about everyone's response was terrible.

So this is Point One: You have to compare the US to the real world, not to some idealized response in a white paper. All of the countries in this chart are advanced economies and we did about as well or better than most of them.

Then there's Point Two: In the entire Vox article, contact tracing is mentioned precisely once. But this is the whole ballgame. All that testing and all that data we collect is primarily to support a vigorous program of contact tracing, especially in a case like this where we already knew early on who the most vulnerable community was (men who have sex with men).

And that's where everything falls apart: despite the heroic efforts of a small group of people, we're terrible at contact tracing and all the data in the world won't change that. What we need is (a) great data collection, (b) a large group of extremely well-trained people, (c) lots of funding, and (d) a population willing to answer the phone and provide intimate data to a government bureaucrat calling about a disease.

We have none of that. A few other peer countries do better, but most of them don't really have it either. And in the US, we have another obstacle: even if we were great at A, B, and C, we are possibly the world's worst at D. Not only that, but thanks to the Fox News paranoia machine we're probably worse on this score than we were before the COVID pandemic. Our monkeypox case rate is currently rising faster than in most peer countries, and the reason is most likely our collective unwillingness to embrace contact tracing as a way of life during pandemics.

So, yes, we should collect better data. We should coordinate local, state, and federal officials more efficiently. We should get this kind of thing up and running faster. We should pour money into it.

But it will never make more than a small difference as long as Americans are widely suspicious of contact tracing. That's our big problem, not a lack of funding or commitment or basic epidemiological expertise. The fault, my friends, lies in ourselves, not the CDC.

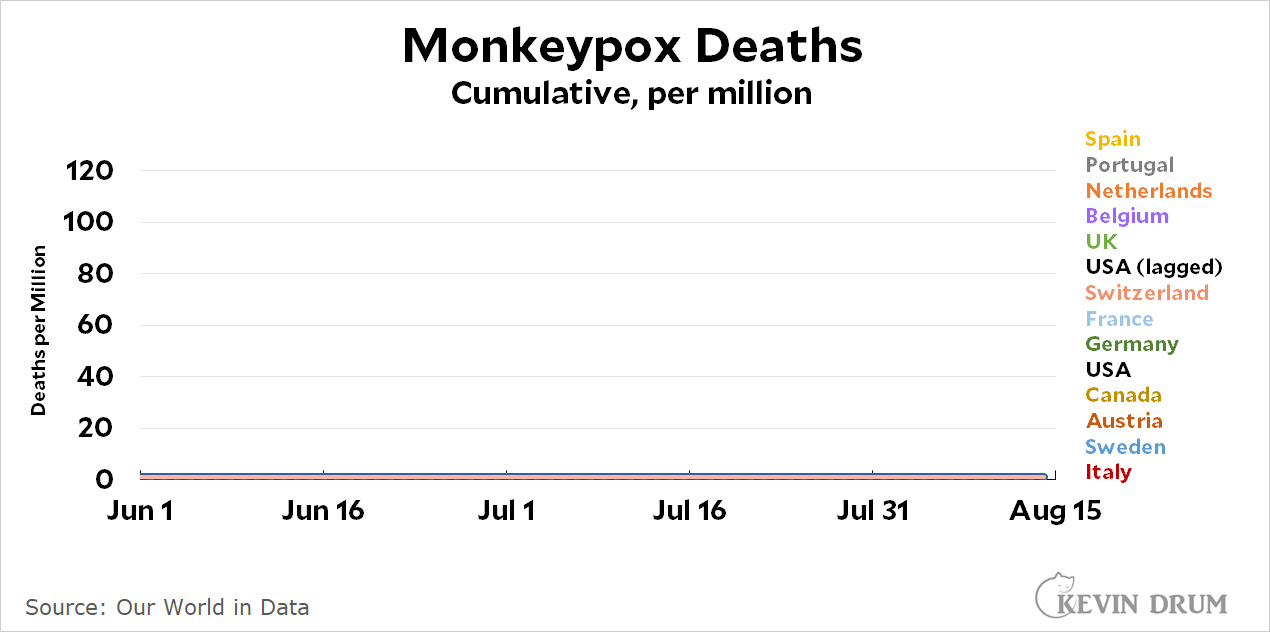

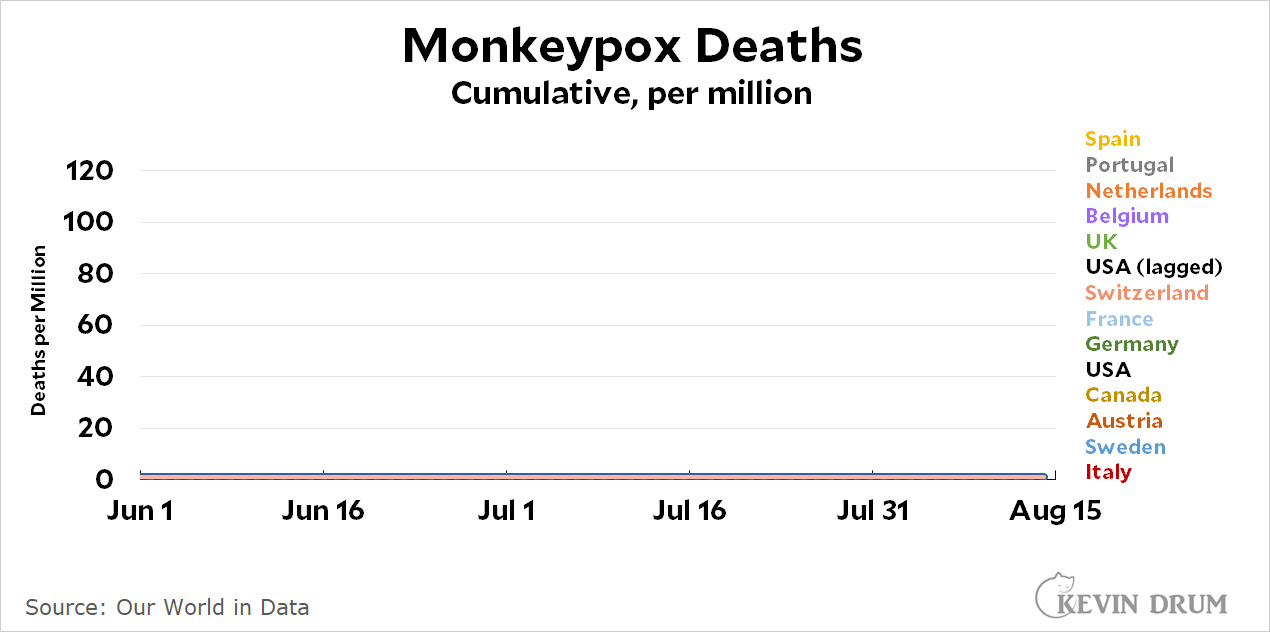

POSTSCRIPT: Here's another chart showing cumulative deaths from monkeypox:

That would be zero for every country on the chart, including the US. Keep this in mind as you evaluate the priority given to monkeypox by the medical community. During the period shown in the chart, 70,000 people in these countries died from COVID-19.

That would be zero for every country on the chart, including the US. Keep this in mind as you evaluate the priority given to monkeypox by the medical community. During the period shown in the chart, 70,000 people in these countries died from COVID-19.