For the past week or so Bob Somerby has been writing about whether doctors believe that Black patients are more tolerant of pain than white patients. In particular, he's been writing about a frequently cited study from 2015 which you can read here if you're so inclined.

Now, Bob is practically trolling me here. This kind of thing is right in my wheelhouse: read the study, explain the ins and outs, and discuss the results. But there's a problem: I've probably read this study half a dozen times over the past few years and I read it again last night. And I've never written about it because I've never been able to make sense of it.

This is weird because the study itself is the simplest possible kind: it's a survey of white medical students and residents—hereafter S&Rs. They were asked 15 questions about biological differences between Black people and white people, four of which were true and 11 of which were false. Here are the questions:

- On average, Blacks age more slowly than Whites.

- Black people’s nerve-endings are less sensitive than White people’s nerve-endings.

- Black people’s blood coagulates more quickly—because of that, Blacks have a lower rate of hemophilia than Whites.

- Whites, on average, have larger brains than Blacks.

- TRUE: Whites are less susceptible to heart disease like hypertension than Blacks.

- TRUE: Blacks are less likely to contract spinal cord diseases like multiple sclerosis.

- Whites have a better sense of hearing compared with Blacks.

- Black people’s skin has more collagen (i.e., it’s thicker) than White people’s skin.

- TRUE: Blacks, on average, have denser, stronger bones than Whites.

- Blacks have a more sensitive sense of smell than Whites; they can differentiate odors and detect faint smells better than Whites.

- Whites have more efficient respiratory systems than Blacks.

- Black couples are significantly more fertile than White couples.

- TRUE: Whites are less likely to have a stroke than Blacks.

- Blacks are better at detecting movement than Whites.

- Blacks have stronger immune systems than Whites and are less likely to contract colds.

The problem with the study is that after presenting the results of the survey it immediately dives into a long and messy bunch of weird measurements and unclear statistics. Its conclusion, based on the survey plus an additional set of questions, is that holding false beliefs doesn't much change assessment of pain in Black people and it doesn't substantially change recommendations of pain relief to Black and white patients.¹ The only noticeable effect is that S&Rs who hold a lot of false beliefs tend to have higher assessments of pain in white people.

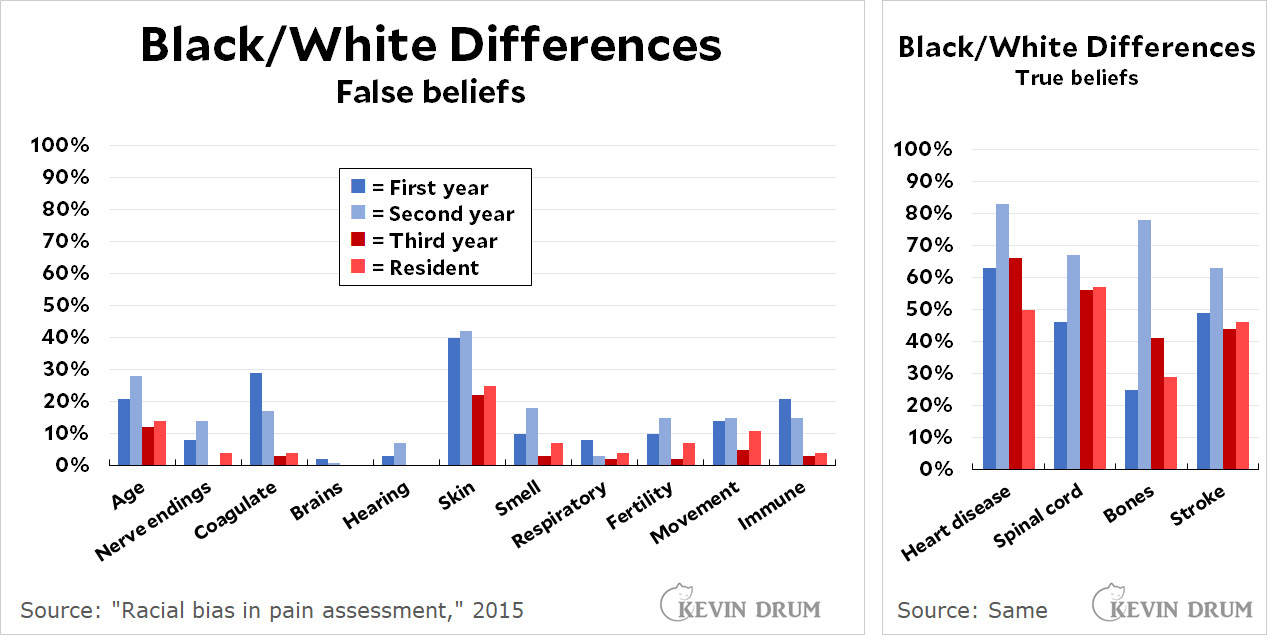

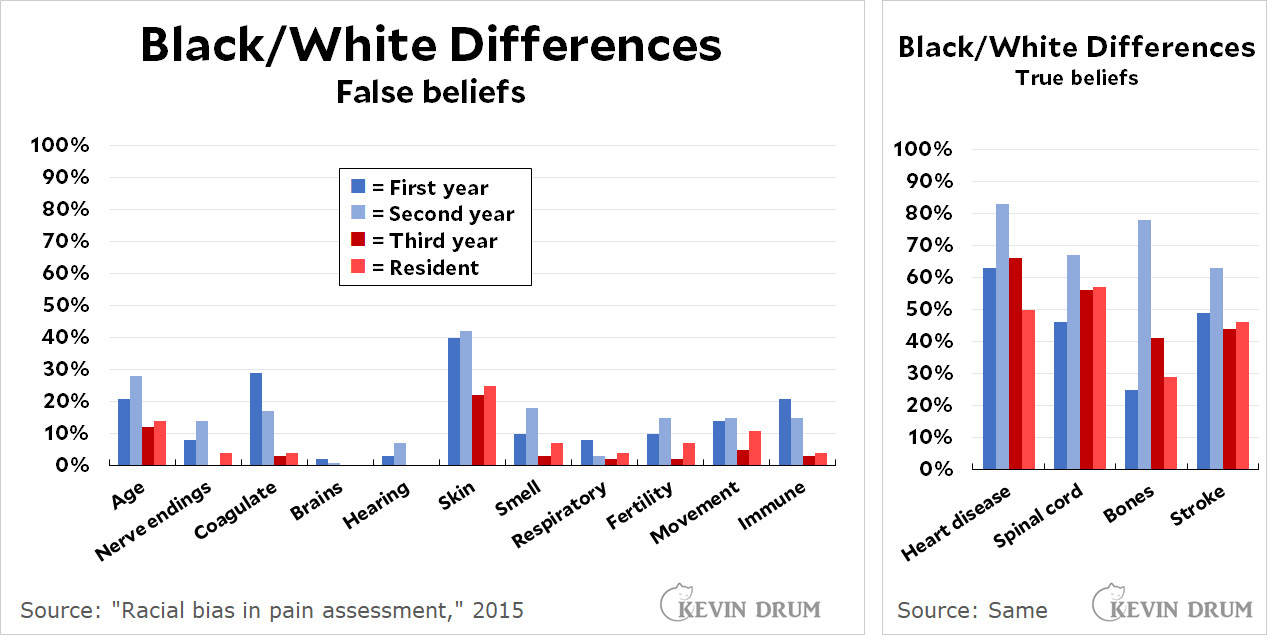

That's a pretty weak result, especially given the deficiencies in the survey design. But for our purposes, let's keep things simple and just take a closer look at the survey responses. First, here are the basic results:

There are a few things to notice here:

- Third years and residents generally do much better than first and second year med students on the false beliefs. Very few mark them as true.

- Second years are more likely to mark something true whether it's true or not. They marked 31% of the statements true, compared to 23% for first years and 17% for third years and residents.

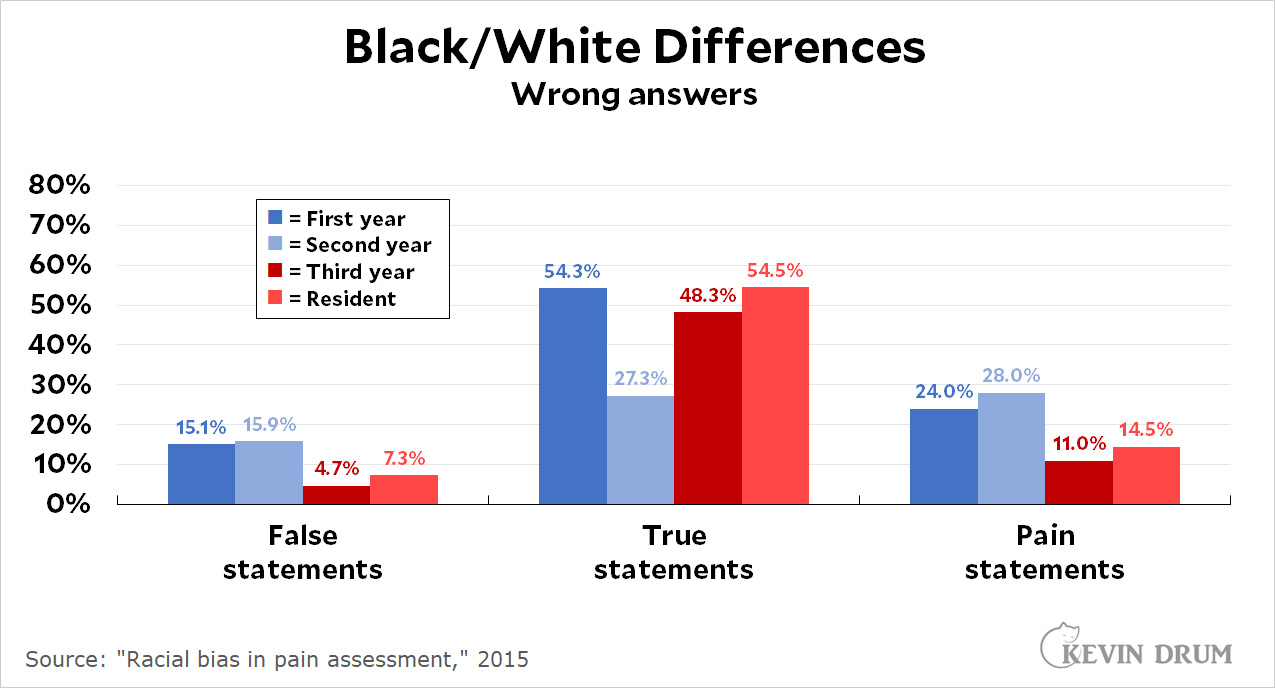

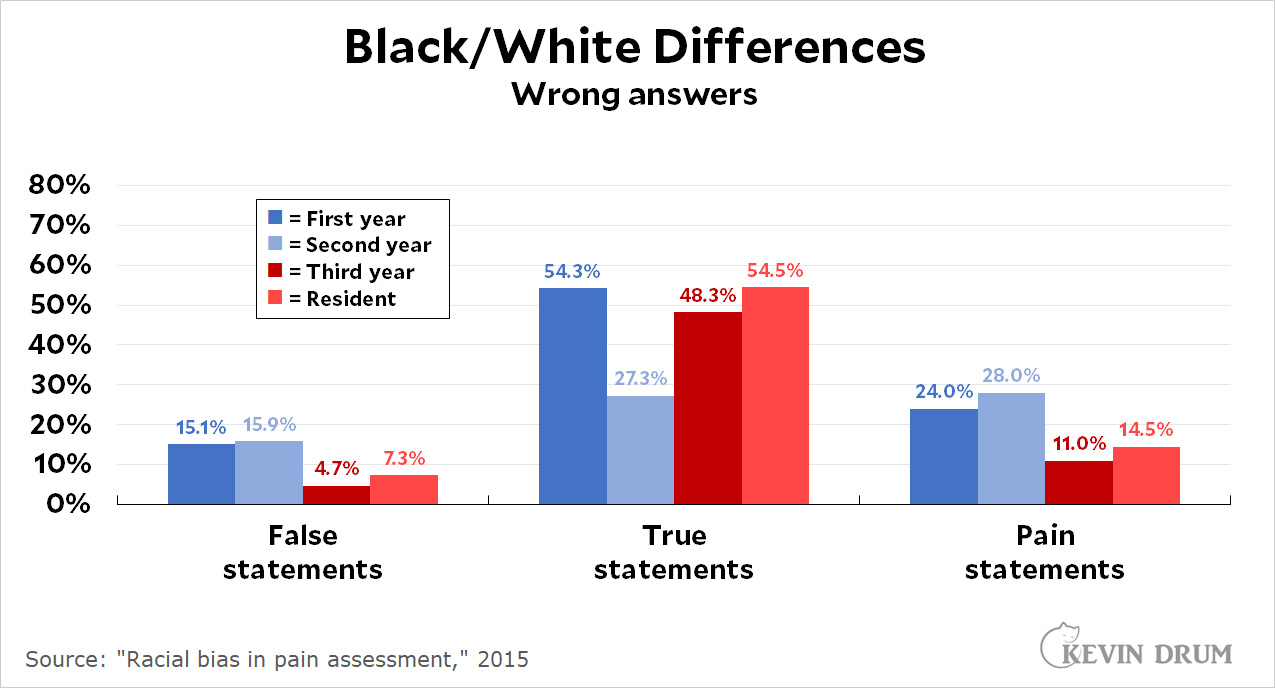

- The respondents do worse on the true statements than on the false ones:

Roughly speaking, about 10% of the respondents mark false statements as true. However, about half of all respondents mark true statements as false. Second year students do much better on the true statements but not so great on the false statements (or the pain statements).

- Answers are given on a scale of 1-6. S&Rs are allowed to mark an answer as "possibly," "probably," or "definitely" true or false. With one exception, which I'll get to, virtually every single person who marked a false statement as true said it was only "possibly true." Among all the false statements, there were 229 marks of "possibly true" and only 9 marks of "probably true." There was not a single mark of "definitely true."

I said there was one exception, and this is it: I didn't count the marks from the question about the thickness of Black skin. This is the huge outlier, with 41% of first and second-years believing it and even 23% of thirds and residents believing it.

So what can we conclude? Not much, but I'd toss out a couple of things:

- There does seem to be a problem with the belief that Black skin is thicker than white skin. This is worth addressing.²

- Beliefs of white and nonwhite respondents are virtually identical. In particular the average score for nerve endings is 1.94 vs. 1.83 (nonwhite S&Rs are more likely to believe it) and 1.76 vs. 1.73 for skin thickness. Overall, the belief in false statements is 2.06 vs. 1.98, meaning that nonwhite S&Rs are slightly more likely to believe them than white S&Rs.

- Belief in false statements is not a problem. The percentages are low and the responses are almost all tentative.

- However, S&Rs are apparently so afraid of saying they believe in any Black/white differences that they do very poorly on the statements that are true.

Overall, this is a dog's breakfast of a study. The authors end up focusing on whether S&Rs who harbor more false beliefs also tend to rate pain lower in Black patients compared to better-informed S&Rs. It turns out they don't, but they do rate pain in white patients higher. However, the amount is smallish; it makes little difference in treatment; and the statistics presented seem cherry-picked and gnawed at a little too carefully. I'm not really sure I put much stock in the authors' conclusions.

I'd recommend that no one cite this study—and if you do, at least cite it correctly. The authors don't make this easy, but if you want to play with the raw data go here and click on "Study 2" and then on "Data - Raw and Cleaned." Be sure to first read the main report carefully, though. For example, you'll want to remove all nonwhite respondents since the study was solely of attitudes from white students and residents. And you'll want to understand the response scale. Etc.

Overall, though, I'd say you shouldn't bother. It's just a simple survey with weak results. The real question is why no one seems to have done much research on this question since 2015. The treatment of Black patients is an issue of high interest these days and you'd think there would be more about it.

¹The measured difference is 15% of a standard deviation. That's pretty small, the equivalent of less than a half inch in height in the human population.

²However, it's worth noting that this is an active area of research that has produced some contradictory results. See here, here, here, and here. That said, most pain isn't affected by skin thickness anyway. If you fracture a bone or have a heart attack, there's no reason to think white people will suffer worse pain than Black people.