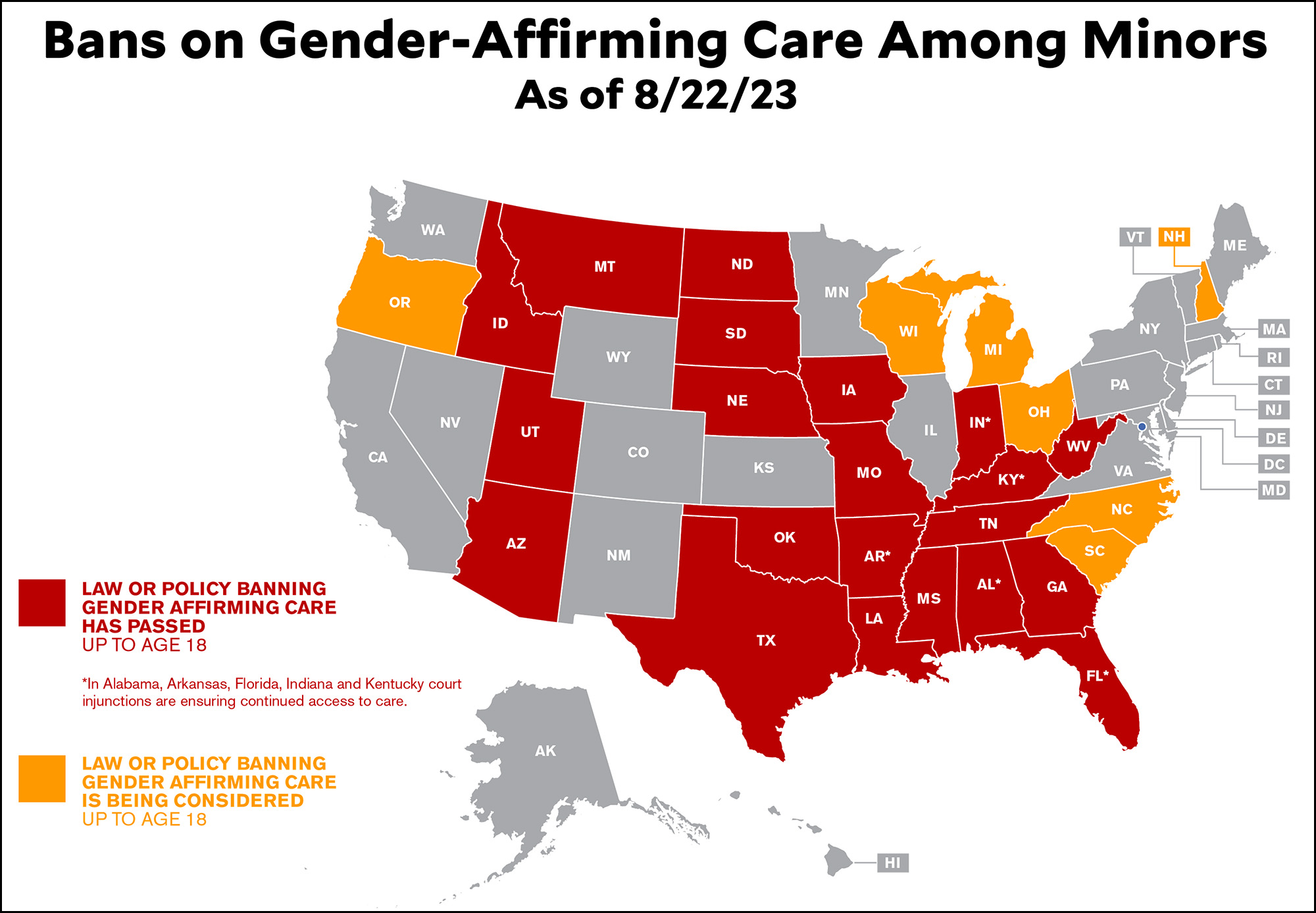

In our Twitter spat a couple of days ago Chris Geidner mentioned a new law that prevented trans kids from getting gender affirming care up through age 18. I corrected that to 17, thinking of the Tennessee law that was recently upheld in federal court. But no. It turns out Alabama has a law that really does go up through age 18, and it too has been recently upheld in court.

But why? The Alabama law talks repeatedly about protecting "minors," who are generally defined as age 0-17. What's the excuse for adding on an extra year?

The answer is that Alabama is one of the few states that defines minors as age 0-18. So at age 18 you still aren't an adult.

But medical care is a big exception. In Alabama, you can get treatment for drugs and alcohol at any age. You can get STD testing at age 12. You can get yourself vaccinated at age 14 (except for COVID). You can get contraceptives at age 14. Or anything else, for that matter:

Any minor who is 14 years of age or older, or has graduated from high school, or is married, or having been married is divorced or is pregnant may give effective consent to any legally authorized medical, dental, health or mental health services for himself or herself, and the consent of no other person shall be necessary.

Now, it isn't unheard of to make exceptions to general age restrictions like this one. Abortion is completely illegal in Alabama, for example, no matter your age. The drinking age is 21, as is the vaping age and the smoking age. You can buy life insurance at age 15 and take out an educational loan at 17. You can't run for governor until you turn 30. The age of consent is 16.

Still and all, the general age of adulthood for medical procedures is 14, and that's without parental consent. Trans care is now basically the only exception even with parental consent, a hysterical submission to the current crusade against trans people from red state Republicans.

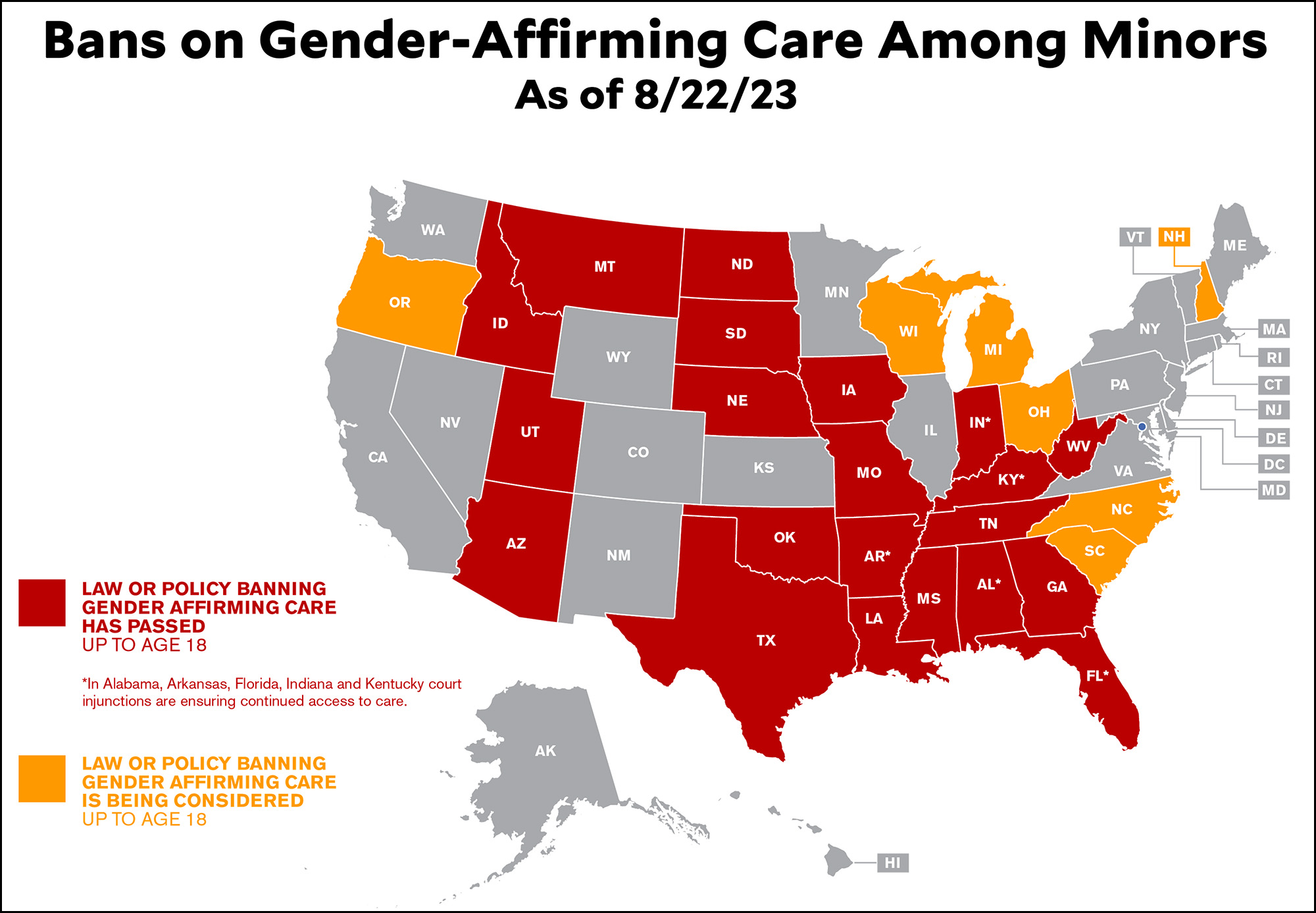

Moral panics like this one generally produce nothing but misery and oppression, and the campaign against gender-affirming care is headed down the same road. It's one thing to display some caution toward procedures that haven't been heavily studied and still have unknown consequences—this is happening in some European countries—but it's quite another to ban them altogether out of bigotry and ignorance. That's what the militant zealots in Alabama are doing, along with their militant zealots in two dozen other states.

Moral panics like this one generally produce nothing but misery and oppression, and the campaign against gender-affirming care is headed down the same road. It's one thing to display some caution toward procedures that haven't been heavily studied and still have unknown consequences—this is happening in some European countries—but it's quite another to ban them altogether out of bigotry and ignorance. That's what the militant zealots in Alabama are doing, along with their militant zealots in two dozen other states.

In the absence of strong evidence in either direction, decisions like these should generally be left up to the patient, their doctor, and their parents. They're the ones best able to make case-by-case judgments. At most, given the current state of our knowledge, states might be justified in mandating a few guardrails (counseling, time restrictions, etc.). But that's it. Banning gender affirming care entirely for minors—the only age at which certain procedures can be done—is nothing more than jumping on the bandwagon of never-ending ugliness that has broken out in the Republican Party in the age of Trump. It's cretinous and disgraceful.