Vox writes about our recent increase in traffic deaths:

According to a 2021 survey of over 1,000 police officers, nearly 60 percent said they were less likely to stop a vehicle for violating traffic laws than they were prior to 2020, when the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police inspired nationwide protests over police brutality, and the pandemic disrupted usual enforcement practices.

....The fact that traffic stops are decreasing while deaths are rising doesn’t necessarily mean that one is causing the other, because correlation does not equal causation, as any good statistics teacher will tell you....Some experts, however, think there’s an obvious link. Enforcement efforts that are high-visibility and focused on safety are shown to reduce risky driving. Experts believe the opposite might also be true.

Here's the problem: this doesn't match the data. Here are traffic fatalities over the past ten years:

Traffic fatalities jumped suddenly in the second quarter of 2020 and then flattened out at their new higher level.

Traffic fatalities jumped suddenly in the second quarter of 2020 and then flattened out at their new higher level.

It's possible this is related to the George Floyd protests, but it seems unlikely since those protests only started at the tail end of the second quarter of 2020. Nor is it likely related to fewer traffic stops. Those didn't suddenly drop off in the second quarter of 2020 and, in any case, can't have an effect until drivers realize that enforcement is down. That takes a while.

By far the most likely explanation is COVID, which exploded precisely in the second quarter of 2020. But why? Why did COVID suddenly make us into reckless drivers? And why have we remained reckless drivers even as COVID has waned?

The truth is that none of this really makes sense. It's unlikely that the sudden spike in traffic deaths has anything to do with George Floyd, and it's more or less impossible that it has anything to do with reductions in traffic stops. It is likely that it's related to COVID, but that just pushes the question a level deeper. What does COVID have to do with driving?

This is, for now, an unsolved mystery.

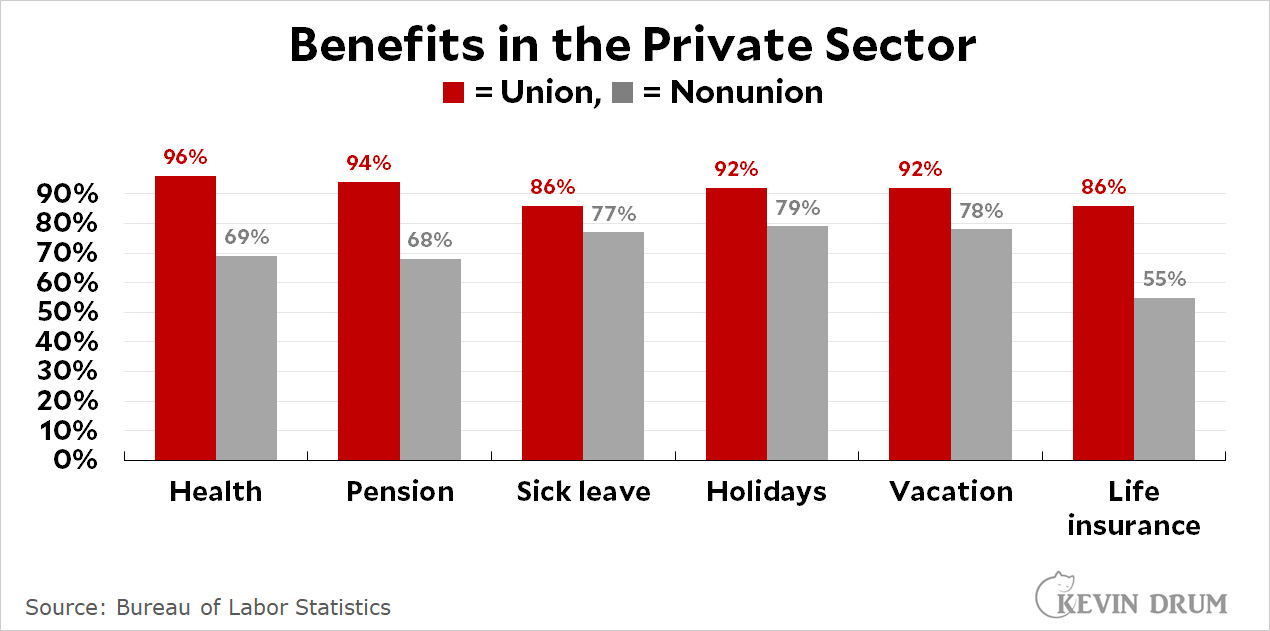

These are the latest estimates from the BLS, and they show pretty clearly that in addition to better pay, union members also have considerably greater access to benefits. I don't imagine this comes as a surprise to anyone, but sometimes it's nice to see the actual numbers.

These are the latest estimates from the BLS, and they show pretty clearly that in addition to better pay, union members also have considerably greater access to benefits. I don't imagine this comes as a surprise to anyone, but sometimes it's nice to see the actual numbers.