Earlier today I asked if the 2018 bank deregulation bill had any effect on the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. The consensus in comments was that deregulation allowed SVB to avoid Fed stress tests that might have uncovered its liquidity problems.

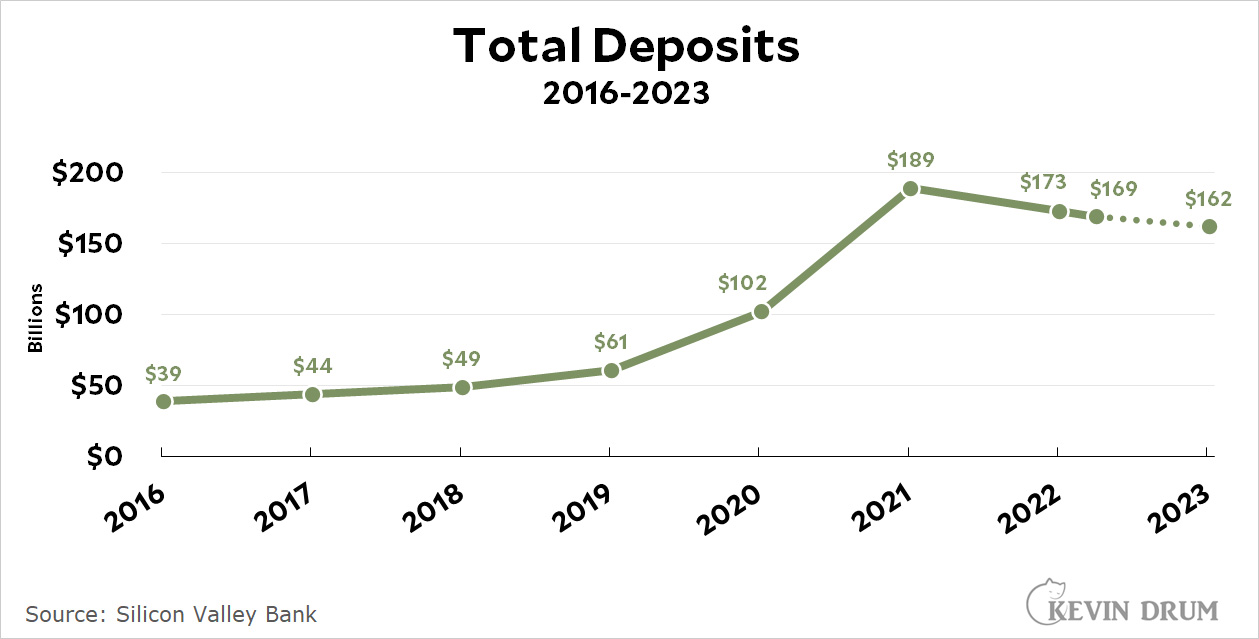

(As a brief aside, it's common to say that SVB bet on interest rates staying low and then took big losses when the Fed hiked interest rates. That's true as far as it goes, but SVB's bond portfolio was marked as Hold to Maturity, which means the losses never showed up on their books. In other words, the problem wasn't interest rates per se because SVB never intended to sell those bonds in the near term. The problem was that the bonds in this portfolio were illiquid because they couldn't be sold without recording a big loss all at once. This isn't an interest rate problem so much as a classic, time-honored liquidity problem.)

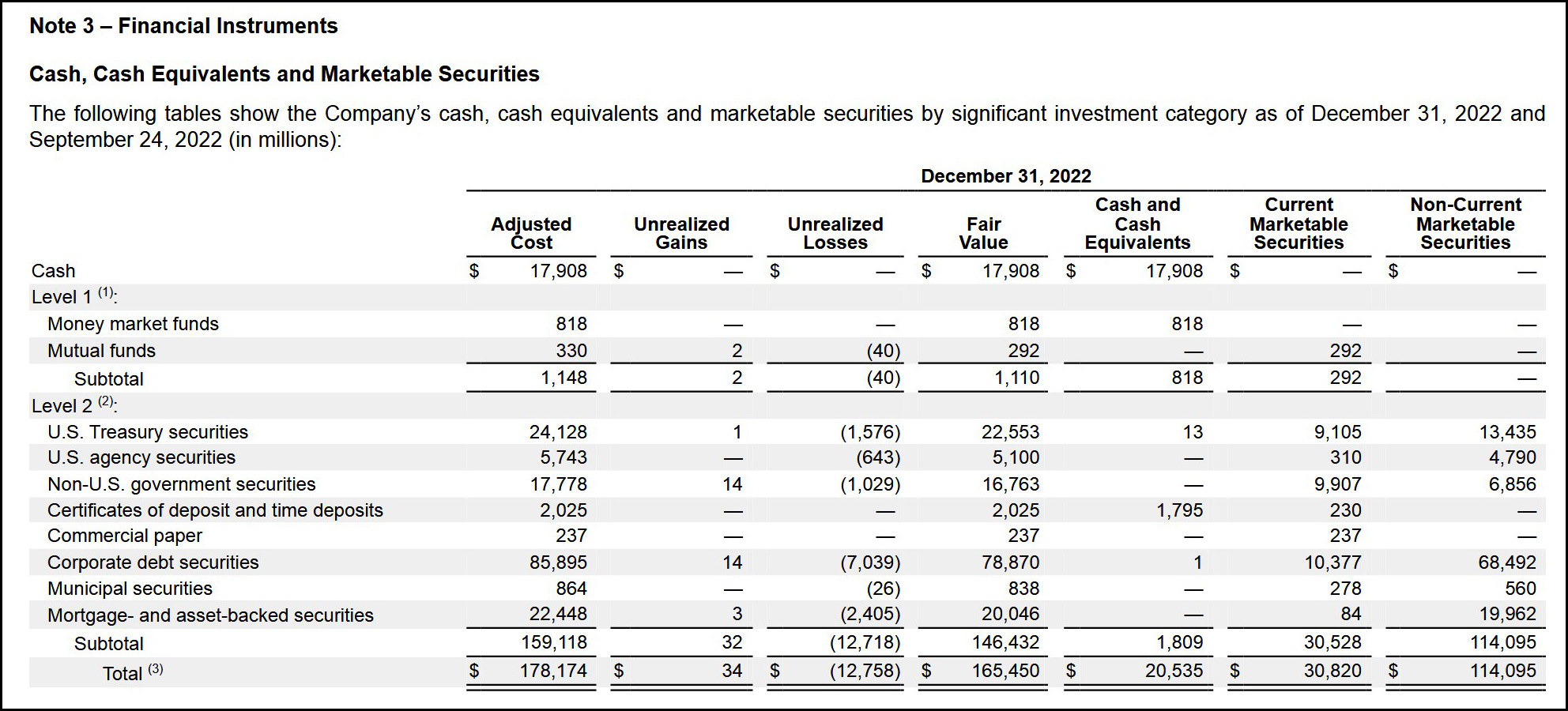

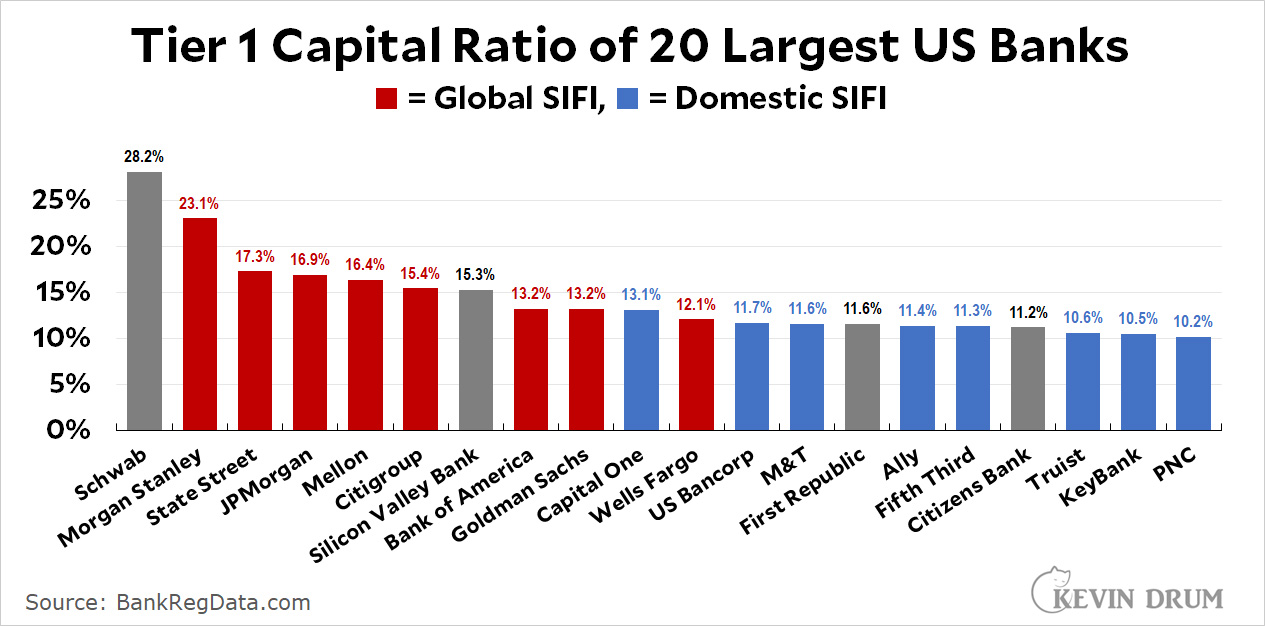

The question is whether this would have been flagged in a Fed stress test. For reference, here are the 20 biggest US banks sorted by Tier 1 capital ratio:

There are a couple of things to take away from this. First, SVB should have been designated a SIFI—a Systemically Important Financial Institution. It wasn't big enough to qualify as a global SIFI, but it was certainly big enough to qualify as a domestic SIFI.

There are a couple of things to take away from this. First, SVB should have been designated a SIFI—a Systemically Important Financial Institution. It wasn't big enough to qualify as a global SIFI, but it was certainly big enough to qualify as a domestic SIFI.

That said, its capital adequacy was excellent, higher than practically every domestic SIFI in the country—and higher than even the new capital ratios imposed on the three biggest US banks last year. Given that, would a liquidity stress test have demanded an even higher capital ratio? I have my doubts, and in any case SVB would have been given time to beef up its reserves.

None of this is meant to imply that SVB's management didn't make mistakes. Their unrecorded losses in long-dated bonds, along with the outflow of deposits caused by the tech crash, had been a widely recognized problem for at least a year. On the flip side, they really did have plenty of high-quality capital and plenty of cash available from selling other assets. They clearly recognized that the outflow of deposits was likely to last longer than they had thought, and they addressed this by (a) selling assets, (b) trying to sell shares, and (c) looking for a buyer. I don't have the banking chops to know if this was sufficiently prudent behavior, but certainly SVB would have been OK in the near term if it hadn't suffered a huge, almost instantaneous run coordinated over social media. The lesson, I guess, is that if you live by tech, you run the risk of dying by tech.