French president Emmanuel Macron is visiting President Biden today, but before the visit he gave a speech at the French embassy. The Washington Post reports that he is not entirely satisfied with American foreign policy:

The Washington Post reports that he is not entirely satisfied with American foreign policy:

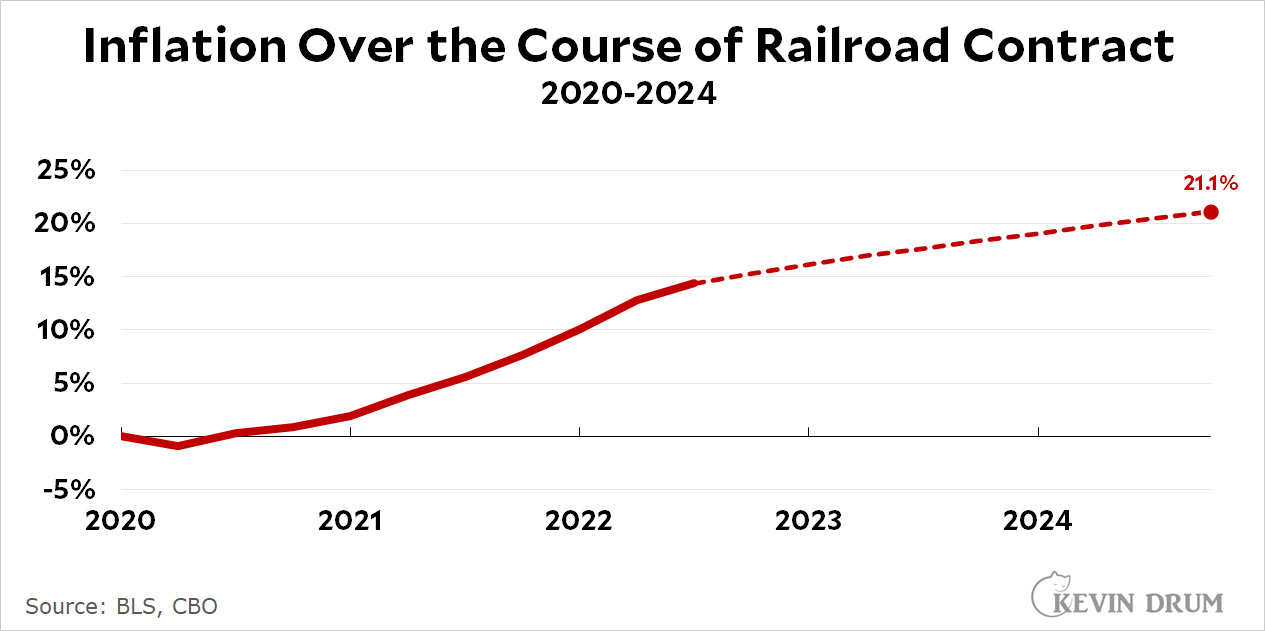

The impact of the Inflation Reduction Act in Europe has proven to be a major point of tension. Macron’s sharp warning of an economic split captures a broader sentiment in European capitals that the IRA, which includes $369 billion in aid to U.S. manufacturers, is a nationalistic measure that will hurt their economies.

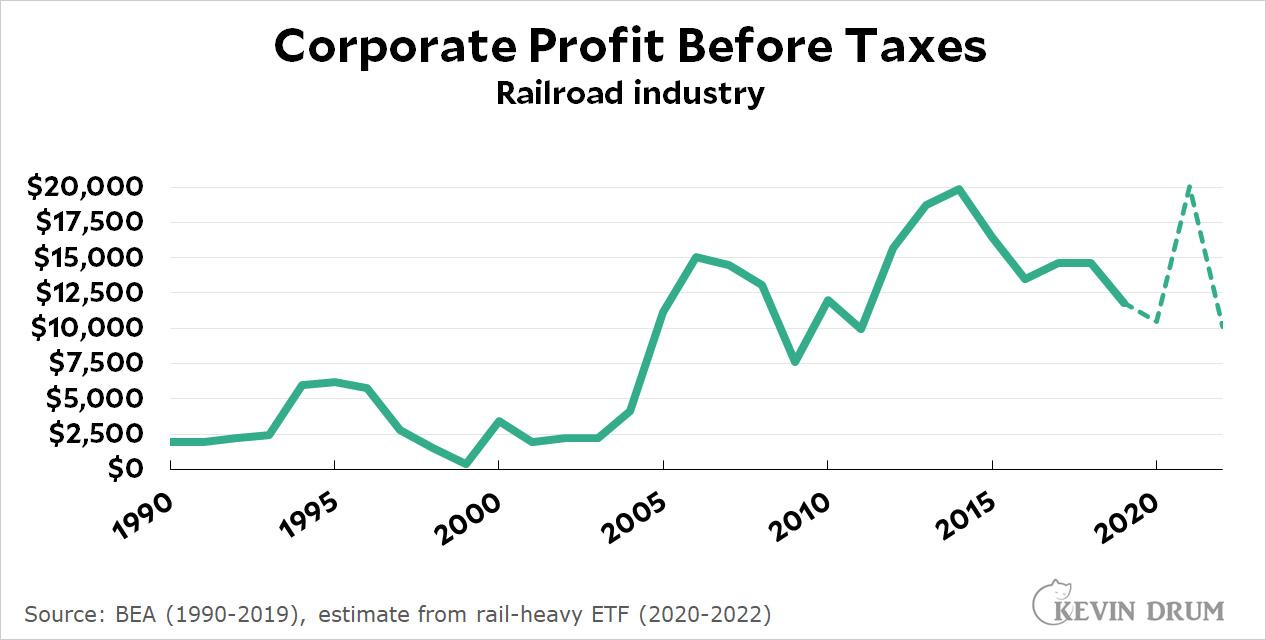

....Macron in his comments Wednesday also took aim at the multibillion dollar Chips Act, which seeks to boost the U.S. semiconductor industry. The danger, he said, is that the United States looks first to itself, “then looks at its rivalry with China — and that Europe, and therefore France, becomes a sort of adjustment variable.”

The Wall Street Journal confirms that Macron's concerns over our climate subsidies are widely shared:

The European Union, South Korea, Japan and the U.K. have all criticized the subsidies, arguing they discriminate against their companies and violate World Trade Agreement rules.

National subsidies are always a point of contention, and I imagine that these will be litigated at the WTO as usual.

As for the CHIPS Act, it sounds like Macron may be thinking less about semiconductor subsidies here and more about a different issue: Biden's ban on exporting advanced chip technology to China. Last month I was curious about how our allies felt about this, since Biden's order also forbids other countries from exporting cutting-edge chips to China if they incorporate any US technology in their products. At the time I hadn't heard of any European pushback, but it sounds like Macron and the EU have more concerns than I knew about. The problem, apparently, is not that Macron opposes the goal of Biden's export ban, just that he's afraid the US is so economically powerful that it can impose unilateral trade sanctions that other countries are then forced to go along with. This is hardly a brand new concern, however, and we'll have to wait to see how it works out.

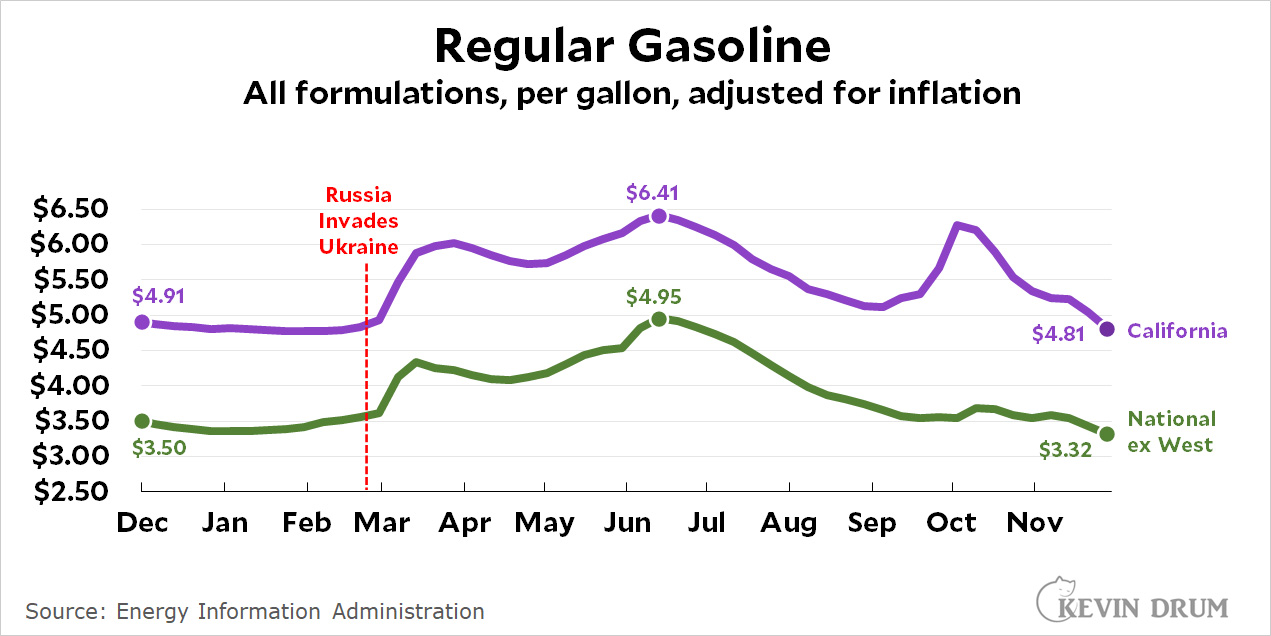

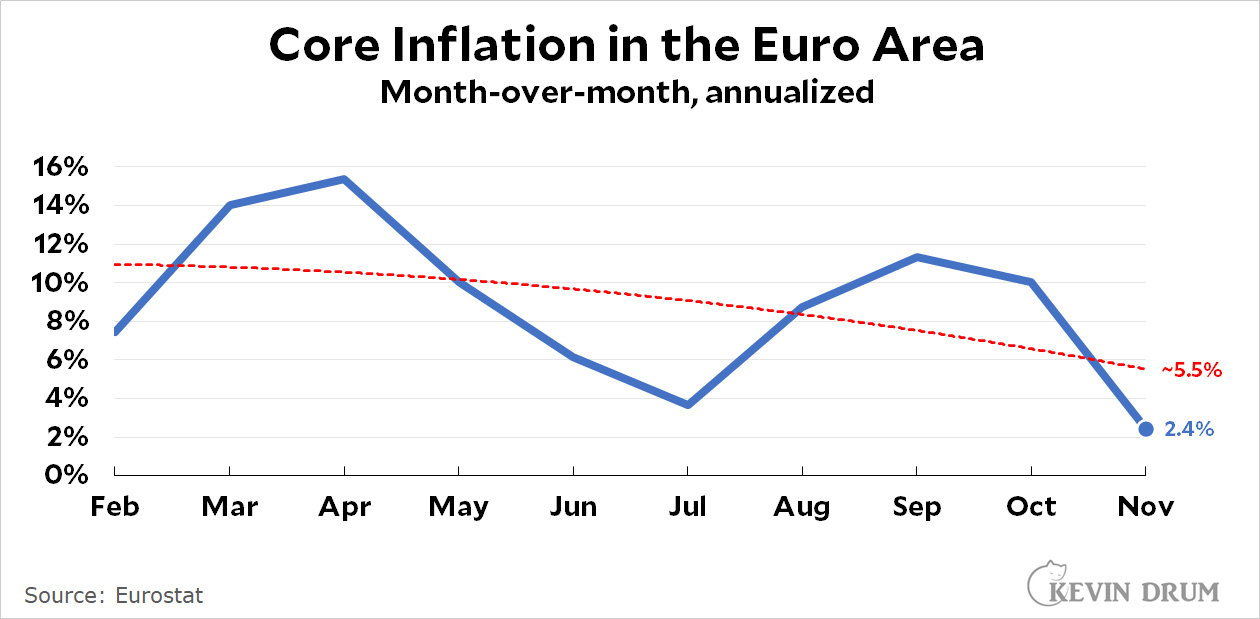

Another interesting tidbit was Macron's comment about the Ukraine War, namely that “the cost of the war is not the same in Europe and in the U.S.,” given Europe’s proximity to Russia and its reliance on Russian oil and natural gas.

That's true! Americans complain about gasoline prices and food inflation, but Europe is facing both of these problems as well as big fuel shortages and scarcities of certain foods. Macron didn't suggest there was anything unfair about this—it's just a natural consequence of geography—but did seem to think that perhaps the US ought to complain a little less about both the cost of its assistance and the occasional reluctance of European leaders to piss off their voters even more given the sacrifices they were already making.