Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through May 4. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Cats, charts, and politics

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through May 4. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

My lunch partner and I were discussing the general question of wokeness and "critical race theory" in schools today, and I promised to look into the whole thing a little more deeply than I have so far (which is roughly zero). I'm not sure I'll follow up on that promise, but when I got home I found that at least a few corners of the internet were frothing over an alleged attempt by the state of California to destroy math education. This turned out to be prompted by an article in Reason, written by Robby Soave, about California's latest draft framework for K-12 math.

The bill of particulars is basically that (1) the framework wants to eliminate advanced math courses, especially calculus, and (2) it spends lots of time on connecting math to social justice concepts like bias and racism.

Does it? You guys don't pay me enough to read the whole framework, but I did demonstrate my dedication to the cause by reading chapters 1 and 2. I will say up front that the framework is practically bursting with edu-jargon and references to allegedly scholarly papers. This is not my cup of tea, but I won't hold it against anyone. So what does the framework say?

First off, it does indeed spend a lot of time connecting math to social justice concepts, but it's worth noting that this is done in a fairly conventional way. Everyone has agreed for decades that math needs to be made "relevant" by posing problems connected to the real world, and the new framework carries on this tradition. The big difference is that some of their examples involve social justice issues. For example:

Ms. Ross selects three word problems to connect with the class’s current read-aloud of George, a novel by Alex Gino that shares the story of a 10-year-old transgender fourth grader and her struggles with acceptance among friends and family.

There are other examples like this, and they're mostly just updated versions of the story problems that we all dreaded back when we were in math classes. I don't see much harm here, though I suppose your mileage will vary.

Second, the framework takes on the issue of tracking, which has been the source of math pedagogy wars since before I was born. The new framework comes down firmly on the anti-tracking side up through middle school, based on the idea that recent neurological research shows that (a) anyone can learn math up to high levels,¹ and (b) advanced kids who take the standard Common Core classes do better than those who are tracked into honors classes:

The overall achievement of the students after the de-tracking significantly increased. The cohort of students who were in eighth-grade mathematics in 2015 were 15 months ahead of the previous cohort of students who were mainly in advanced classes (MAC & CAASPP 2015).

As for calculus, the authors are unhappy about a "rush to calculus" that's mostly motivated by an insane competition for entrance to elite universities and "does not lead to depth of understanding or appreciation of the content." However, they also explicitly say this:

All students can take Common Core-aligned mathematics 6, 7, and 8 in middle school and still take calculus, data science, statistics, or other high-level courses in high school.

These are not the words of people who hate high school calculus.

In the end, the framework is guilty of the following sins:

I won't pretend that I agree with all of this, but neither do I think it spells the end of decent math education here in the Golden State. The bottom line is that if you hate the idea of schools incorporating social justice into their classrooms then you'll hate it here too. If not, then you won't. But either way, I doubt that it will have much effect one way or the other on the ability of students to learn math.

¹Without diving too deeply into this, I'll note that this belief is driven in large part by mindset theory, which says that children learn better if they are taught to adopt a "growth mindset." A growth mindset is one in which children believe that abilities like intelligence can be improved over time. Conversely, a "fixed mindset" teaches that things like character, intelligence, and creative ability are largely static.

Unfortunately, mindset theory hasn't fared well in recent research that has attempted to replicate the original mindset studies. Frankly, all the social justice stuff bothers me less than the framework's unquestioning reliance on a theory that hasn't panned out in the decade since it was introduced. If this is typical of their approach, there's little chance that the new framework will be successful.

This is a row of aspen trees at Aspendell, about ten miles southwest of Bishop. It is four images stitched together in Photoshop.

Too dense for display at this size? Maybe. Perhaps three images would have been better:

Alternatively, maybe this is just flatly too dense and detailed for display at this size no matter how I crop it. I'm not sure, but there's no question that it lost too much resolution when I reduced it to 2000 pixels wide. It's just not sharp enough now.

So what happens when the pandemic is over? Do lots of us continue working from home? Or do the bosses want us back in the office? JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon, who has a quarter of a million people working for him, knows what he wants:

Coming out of the pandemic, Mr. Dimon is eager for other signs of normalcy. More JPMorgan employees will return to the office starting this month, though Mr. Dimon acknowledged they aren’t all happy about it. But the remote office, he said, doesn’t work for generating ideas, preserving corporate culture, competing for clients or “for those who want to hustle.”

“We want people back at work and my view is some time in September, October, it will look just like it did before,” Mr. Dimon said. “Yes, people don’t like commuting, but so what?”

To Mr. Dimon, commuting is better than the alternative. “I’m about to cancel all my Zoom meetings,” he added. “I’m done with it.”

Only time will tell, but I suspect there are more bosses like Dimon than we think. Dimon wants people back in the office by October, and in the year following that I'll bet that more and more bosses will come to agree with him.

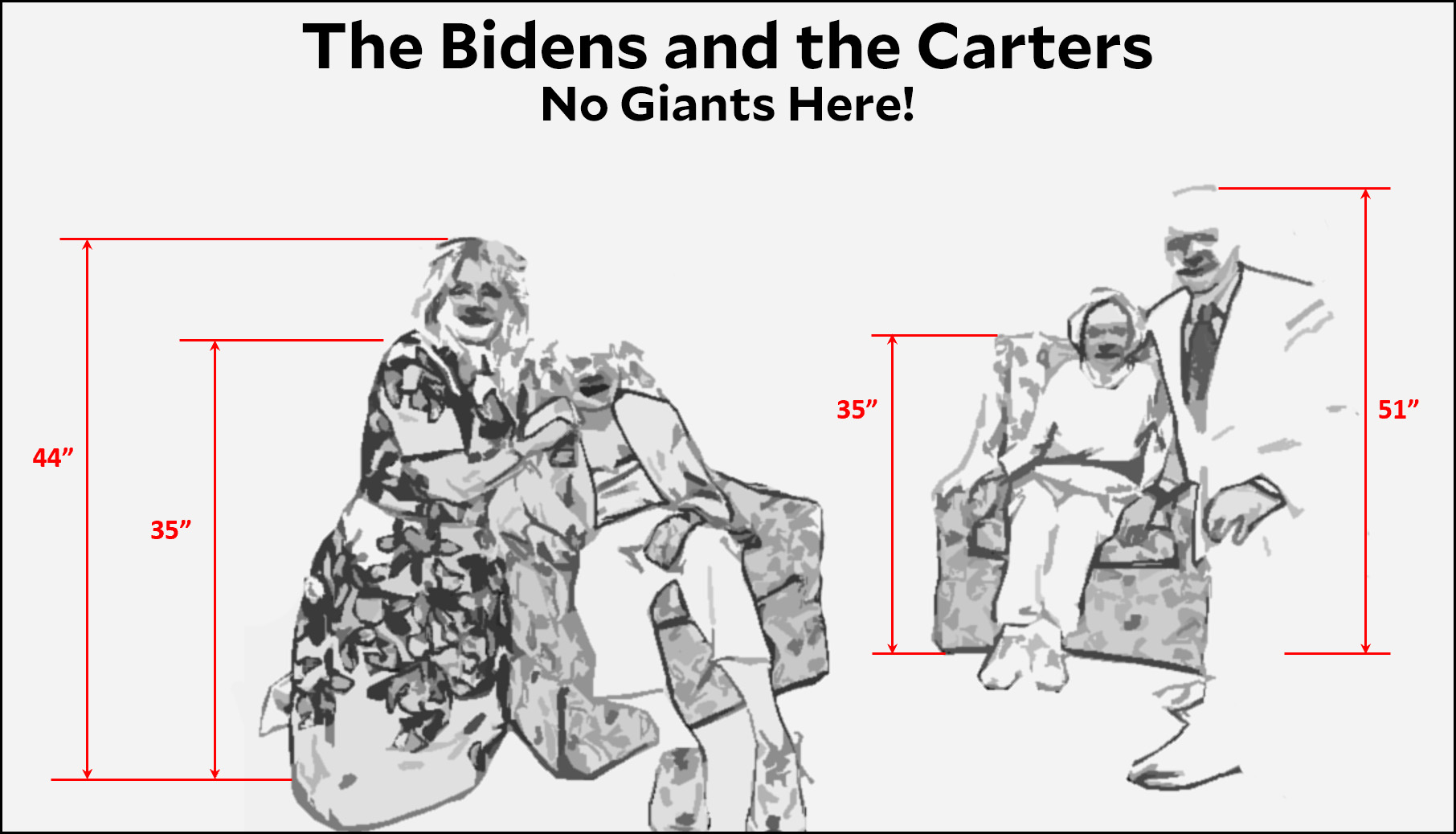

Joe and Jill Biden visited Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter a few days ago, and yesterday a photo of the visit was released. It's been making the rounds of the internet every since.

The Bidens look like giants compared to the Carters! What's going on?

There's a lot of talk about flash shadows and wide-angle lenses and so forth, but I don't buy it. I don't think the lack of shadows makes much difference, and the lens has introduced only a small bit of distortion (take a look at the picture frame on the far left to see how little there is).

In fact, this is all pretty simple: The Bidens really are bigger than the Carters and Jimmy is slouching, which makes him look even smaller than normal. Here are the measurements:

The chairs look fairly normal, so I'm figuring them at 35" tall and then using that as a baseline to measure the Bidens. Joe clocks in at 51", which seems about right. I'm a couple of inches taller than him and I stand 53" or so when I'm kneeling.

Jill Biden is six inches shorter than Joe, and in the picture she measures seven inches shorter. That may be measuring error on my part, or maybe she's just not standing as fully rigid as Joe the politico.

The wide-angle lens does make the Bidens slightly wider than they should be, but only by a little. The main reason they look like offensive linemen is because the Carters are so thin.

So that's that. To the extent that there's an optical illusion here, it's mainly because Jill/Jimmy are a lot closer to the camera than Joe/Rosalynn. But overall, the difference in sizes is quite real.

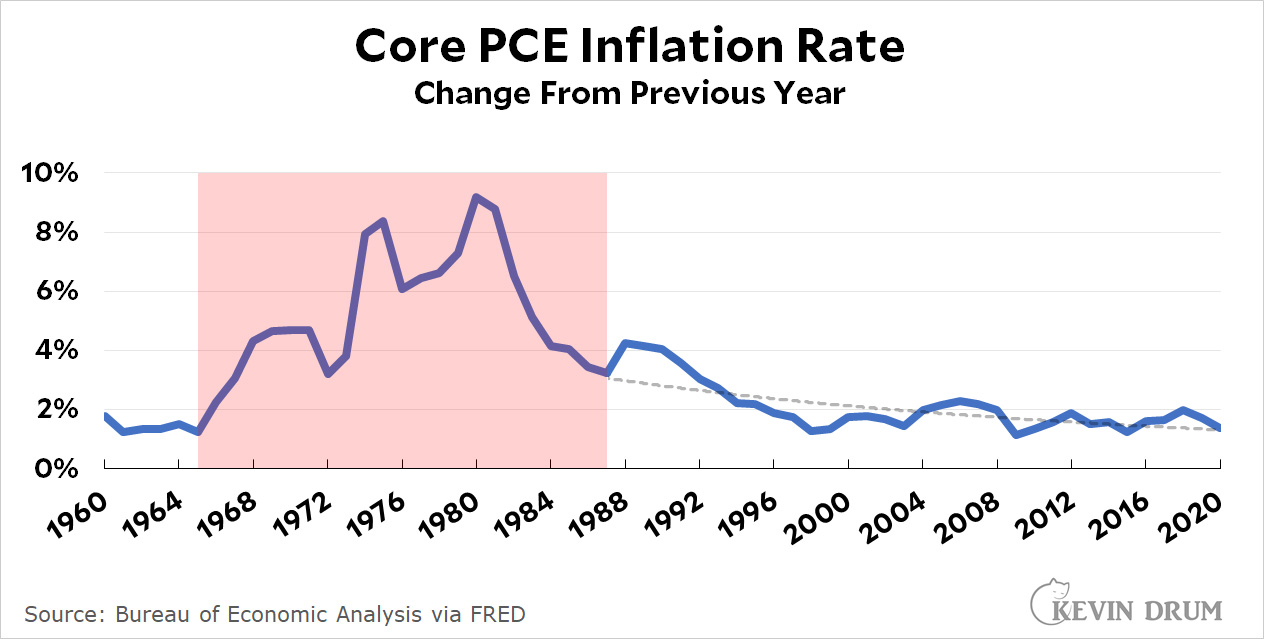

Paul Krugman is annoyed with Mohamed El-Erian, who says that inflation is here to stay and we should start responding to it. It's not entirely clear why El-Erian thinks this, but I suspect that it's yet another example of the trauma suffered by people who lived through the '70s.

This is a syndrome similar to beliefs about rising medical costs. As it turns out, it's not true that medical costs have been skyrocketing forever. They've been relatively restrained for the past 60 years with the exception of a 15-year spike in the '80s and '90s. Likewise, inflation has been relatively restrained over the past 60 years with the exception of a 20-year spike from the mid-60s through the mid-80s:

Since that spike ended, inflation has been trending steadily down. High inflation is neither normal nor inevitable in postwar American history.

The next line of attack is usually to highlight some particular commodity that's displaying very high rates of price growth. Chlorine tablets, for example. Or softwood lumber. But by definition, there are always a few items that top the price list at any given time. That fact means less than nothing.

And then we turn to food, a staple of nightly news shows. For some reason, it's been a favorite of NBC News lately, and even my own wife has turned against me on this. "Prices are sure up at Gelson's," she told me yesterday, knowing that I couldn't argue because I never look at prices. But whatever anecdotal evidence you have, the numbers just don't back you up:

Food has followed a trend similar to overall inflation: It spiked from the mid-60s through the mid-80s, but has been in the range of 1-3% for the entire rest of the postwar period.

But wait! What about that little spike at the very end of the chart. Let's zoom in:

This is a monthly look rather than an annual look. As you can see, food prices have been extremely restrained for the past five years, spiking only in April 2020, just as the pandemic hit. Food prices almost immediately began to fall after that, and the most recent monthly reading shows food inflation at 3%.

I would not be surprised if we saw some short-term inflation as we emerge from the pandemic faster than suppliers thought we would and consumer demand outstrips supply. I also wouldn't be surprised if $6 trillion in federal spending generates some short-term inflation.

But are there reasons to think that either food inflation or overall inflation will suddenly defy history and spike upward for years at a time? I guess you never know. Go ahead and make your case. But it better be a good one.

So how is everybody doing on the COVID-19 front? Here are cumulative COVID-19 cases for the ten largest states. I'm showing just the past few months so that the differences are visible to the human eye:

Total cases to date range from 8.9% (Pennsylvania) to 10.4% (New York). California is flattening out at the moment, while every other state is continuing to rise.

I'm really unsure what lesson to take here. On the one hand, sure, some states are doing better than others. On the other hand, the differences aren't huge. To some extent I think that's because different state regulations have (a) been less different than you'd think, and (b) are playing second fiddle to local and corporate rules anyway. Texas can declare that no one needs to wear masks, but if restaurants and supermarkets continue to require them then people will wear masks.

UPDATE: I made a mistake in the original version of the chart, omitting Pennsylvania and adding New Jersey. Both the chart and the text have been corrected.

Peter Orszag says that I'm wrong about America's bridges: we really need to increase funding to repair and rebuild them if we want them to remain in decent shape. His strongest argument is that instead of looking at the past, we need to look at the future:

Consider the age of American bridges. Not surprisingly, bridge quality tends to diminish as a bridge ages, especially toward the end of its useful life. Today, the average bridge in the U.S. was built in 1975, making the average age 45 years. In 1992, the average age of a bridge was 34 years. And today a quarter of bridges are 60 years old, up from 15 percent in 1992. As the bridges grow older and a larger share of them approach the end of their useful lives, it will cost more to maintain or replace them than a backward-looking indicator would suggest. Without investment beyond current levels, bridge quality will decline.

I'll buy that.¹ I'm not actually opposed to spending more on roads and bridges, and I've long favored an increase in the gasoline tax to fund exactly that. So we're not that far apart, especially since President Biden's infrastructure plan includes only $115 billion for roads and bridges. That's $11 billion per year, which is hardly a king's ransom.

For what it's worth, my main gripe is really with the overall conventional wisdom that US infrastructure is falling to pieces. Some of this comes from the American Society of Civil Engineers, which is naturally in favor of lobbying for more civil engineering projects and tells us on an annual basis that our infrastructure is crumbling. I don't hold that against them, but I am perpetually surprised that their lobbying is accepted so credulously as some kind of unbiased assessment.

Beyond that, I suspect that our New York-centric national media plays a role here too. If you live in New York City, with its potholes and train failures and traffic jams and century-old water tunnels, infrastructure porn is probably a pretty easy sell. Outside of New York, however, things are not nearly so bad.

I suppose this is yet another example of my view that most things are not as bad as we're often led to believe. But I hold this view only because it's true. There are things that are getting worse, but for the most part we are victims of politicians who get more votes if they scare people and media folks who get more clicks if they scare people.³ This is why I'm instantly on red alert every time I read a story (or listen to a politician) telling us how bad something is without also telling us how it compares to previous years and/or other countries. That comparison is everything.

¹In fact, if you want a good example of this, just take a look at Italy. They built a ton of bridges right after World War II and most of them were designed for a 50 service life.² Everything was hunky-dory through the aughts, but Italy hadn't maintained their bridges very well and then, just when the need was greatest, was unable to maintain them thanks to the Great Recession. The result is that a bridge system which had a pretty enviable record from 1950-2000 suddenly began killing people in large numbers.

²It's worth noting that this is for everyday bridges, the kind that are workhorses of daily commutes but that no one notices. The big, impressive bridges that cross scenic gorges and end up on postcards are generally designed to last much longer.

³Plus, of course, the usual problem that "Bridges Continue Not to Collapse" isn't much of a news story. If a bridge collapses, it's news. If a bridge stays intact, then it's just a bridge.

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through May 3. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Why did primates and then humans develop a facility for advanced language? One theory is that it helped primate tribes defend themselves better against predators and other dangers. Before the development of language here's an example of tribal coordination when a saber-toothed tiger drops out of a tree with lunch on its mind:

SOMEONE: Eek!

SOMEONE ELSE: Arrgh! [Kill it!]

At that point everyone panics and either runs away or attacks the tiger depending on their personal levels of bravery and stupidity. Result: Satiated tiger. Here's how it goes after the development of language:

SAM: Tiger!

TRIBAL LEADER EDWARD: Fred, grab that big stick and start waving it. Joe, take point. Bob and Andy, you're on flank. Charlie, go get some fire.

Result: Dead tiger.

This is not a bad theory, as these kinds of theories go, but there's a better one based on the idea that the greatest threat to humans is other humans. In operational terms, it means that the development of language was mainly due to a desire to gossip about each other.

This must have been a powerful force. It didn't come for free, after all. It required changes to the larynx that made choking more likely, and it required the development of a large brain, which needed more energy and made childbirth more dangerous.

Nevertheless, for a dominance-hierarchy species like ours, knowing who's up and who's down was critically important. And affecting who's up and who's down was the difference between living a decent life and being tossed to the wolves as a small child. Naturally this started a linguistic arms race, since tribal dominance depended on ever-escalating subtlety and nuance among the gossipmongers. The side effect of all this was the eventual ability to construct pyramids and solve differential equations, but that was never the original plan.

So time went by and language became ever more sophisticated, as did cooperation and betrayal. We invented writing, which provided new scope for gossip and backstabbing, and then movable type. Then there was the penny post and telephones and finally social media.

And this explains what social media is really for: bitching and moaning and talking shit about other people. There is nothing new about this, and it taps into the core motivation for developing language in the first place.

There's more, of course. The big difference between, say, telephones and Facebook, is that Facebook is generally more open and blunt. But didn't I say that language had grown ever more sophisticated and subtle over the years? I did. So why is Facebook famous for being rude and stupid?

Answer: Because it's populated mainly by idiots. No one with any sense would do any serious scheming on Facebook even if they had all their privacy settings applied correctly. It's just too risky. The best and most serious communicators in the modern world use social media for occasional propaganda, but otherwise stick to telephones and encrypted emails and so forth.

This is the basic story of social media. It seems like it should be the latest and greatest advance in human communication, but it's not. Just the opposite: It's designed to appeal to one of the core motivations of humankind, but only in the most brutal, unsubtle way. This makes it mostly a way to corral kids and unsophisticated communicators away from everyone else, which is why it seems like such a cesspool. It's how kids and idiots have always talked, but in the past we've mostly been able to ignore them.

And we take it seriously even when we shouldn't. Don't get me wrong: kids and idiots can cause a lot of harm. This is why staying abreast of social media is important. But it needs to be seen for what it is: a communication medium that appeals to our strongest human instinct—meanspirited gossip—but is mostly just a distraction from the real centers of power and sophistication.

And now I shall tweet out a link to this blog post.