Over the past few days, a million pundits have become instant experts on the finances of Silicon Valley Bank. They are outraged that no one before now noticed the bleeding obvious: SVB was a reckless and fragile bank, a literal time bomb on the edge of collapsing thanks to foolish business practices.

Now, 20/20 hindsight is great, but I've been digging into this for days and I just don't buy the narrative. I'm not saying SVB is faultless, but I am saying it was basically a sound bank facing some modest headwinds. Which they were addressing.

I have receipts for all this. They are mostly based on three documents:

- SVB 10-Q for 4Q2022

- SVB mid-quarter review for March 8, 2023

- SVB Basel III Disclosure for 4Q2022

Let's dive into the big issues surrounding the collapse of SVB.

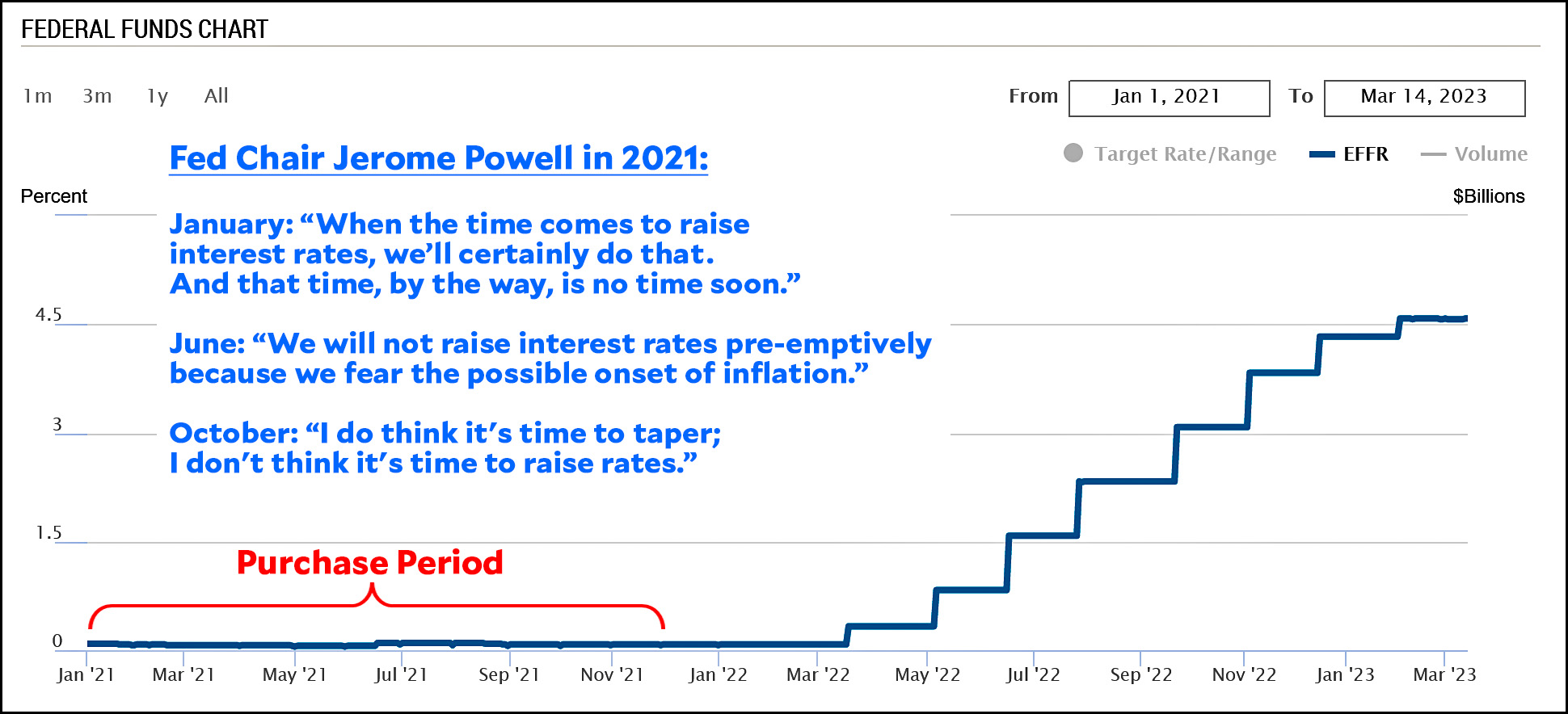

The bond portfolio. SVB had about $90 billion invested in long-dated treasury and mortgage bonds. This portfolio was vulnerable to interest rate risk, and SVB probably should have hedged that. However, keep in mind that nearly the entire portfolio was purchased in 2021:

At the time, there was little reason to think interest rate risk was high. There was certainly no reason to think that Jerome Powell would turn on a dime and not only raise rates, but raise them at an astronomical rate. And anyway, all of the bonds were marked as Hold to Maturity, which meant their losses never showed up on SVB's books and probably never would have.

At the time, there was little reason to think interest rate risk was high. There was certainly no reason to think that Jerome Powell would turn on a dime and not only raise rates, but raise them at an astronomical rate. And anyway, all of the bonds were marked as Hold to Maturity, which meant their losses never showed up on SVB's books and probably never would have.

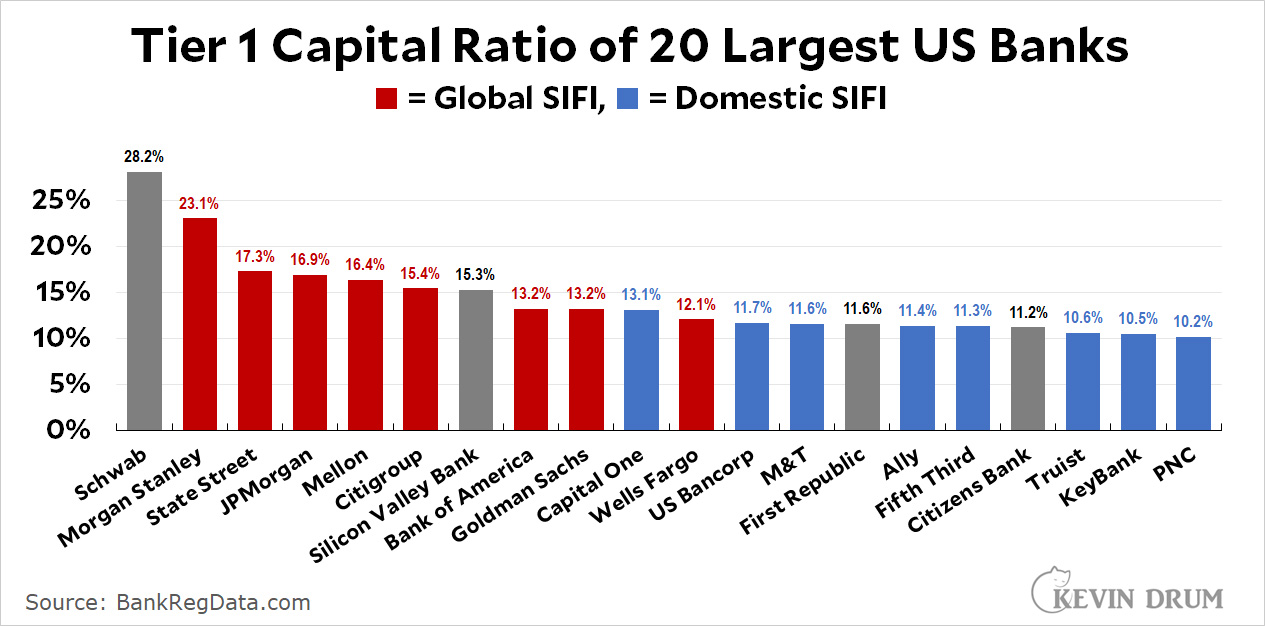

The 2018 deregulation. As best as I can tell, this had no effect at all on SVB. Most of the loosened regulations didn't apply to SVB, and the ones that did would have had no effect because SVB was already capitalized as strongly as a global SIFI and had plenty of liquidity. Their Tier 1 capital ratio was 15.3%; their CET1 capital ratio was 12.2%; and their leverage ratio was 8%. Those are way above anything required by regulators both before and after the 2018 law was passed.

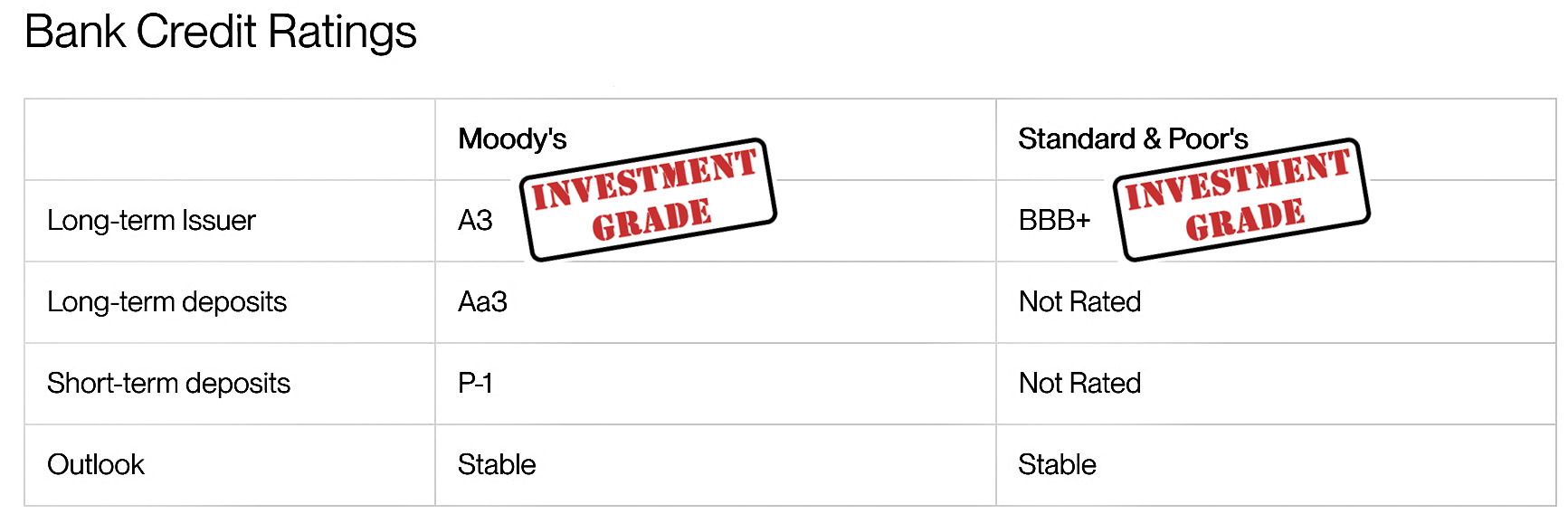

SVB's situation was absolutely not a secret. Maybe you and I didn't know about it because we didn't care, but it was well known to everyone who followed SVB. Their unrecorded losses produced a slight amount of nervousness, but that was all. Investors had no worries: after a big fall in 2022 when the tech boom slowed, SVB's stock was up nearly 40% since the start of the year. Analysts had no worries: they almost unanimously recommended SVB as a buy. Rating agencies had a bit of worry, but nonetheless rated SVB as investment grade.

SVB's situation was absolutely not a secret. Maybe you and I didn't know about it because we didn't care, but it was well known to everyone who followed SVB. Their unrecorded losses produced a slight amount of nervousness, but that was all. Investors had no worries: after a big fall in 2022 when the tech boom slowed, SVB's stock was up nearly 40% since the start of the year. Analysts had no worries: they almost unanimously recommended SVB as a buy. Rating agencies had a bit of worry, but nonetheless rated SVB as investment grade.

SVB responded properly. In response to concern from Moody's about the worsening outlook for the tech sector, SVB consulted with Goldman Sachs and then announced that it would sell $20 billion of its assets at a $2 billion loss and then do a $2 billion capital raise to make up for the loss. This was perfectly prudent. It gave SVB plenty of cash to handle deposit outflows, while diluting its stockholders a bit in order to keep its capital buffers high. Moody's downgraded SVB in response, but this was actually a vote of confidence. They had intended to downgrade SVB two notches, but after the restructuring plan was announced they limited the downgrade to one notch.

SVB responded properly. In response to concern from Moody's about the worsening outlook for the tech sector, SVB consulted with Goldman Sachs and then announced that it would sell $20 billion of its assets at a $2 billion loss and then do a $2 billion capital raise to make up for the loss. This was perfectly prudent. It gave SVB plenty of cash to handle deposit outflows, while diluting its stockholders a bit in order to keep its capital buffers high. Moody's downgraded SVB in response, but this was actually a vote of confidence. They had intended to downgrade SVB two notches, but after the restructuring plan was announced they limited the downgrade to one notch.

On the morning of Thursday, March 9, SVB was solvent and perfectly capable of servicing its customers. It had some long-term challenges, but nothing life threatening. It was fine.

So what happened?

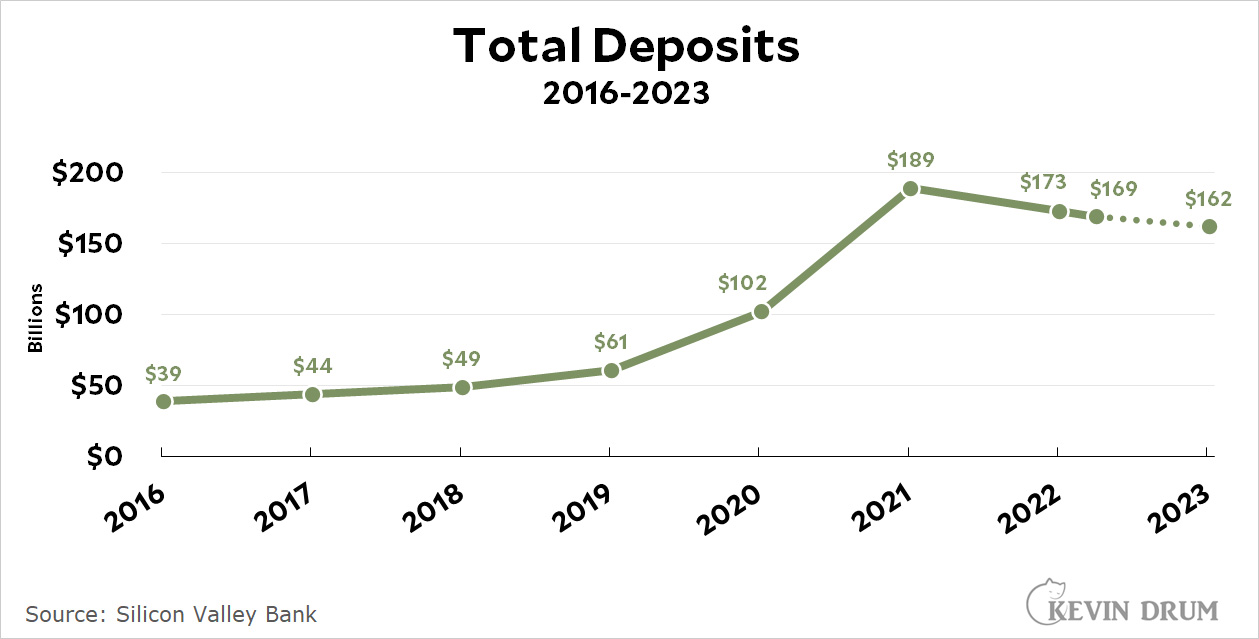

SVB really had only one problem: the pandemic had created a tech boom that saw the formation of hundreds of new startups. VC financing for all these startups flowed into SVB and spiked their deposit level from $61 billion to $189 billion.

In 2022, the tech boom went sour, and that meant no more startups and no more VC financing. As a result, existing startups had to pull money out of their SVB accounts to fund ongoing operations, and that led to a drop in deposits from $189 billion to $169 billion (as of March 8).

This was obviously concerning since SVB was heavily reliant on startup money. However, there was no reason to think that deposits would shrink anywhere near enough to actually jeopardize their solvency.

This was obviously concerning since SVB was heavily reliant on startup money. However, there was no reason to think that deposits would shrink anywhere near enough to actually jeopardize their solvency.

So what happened?

Nobody knows. Founders Fund, the venture capital fund co-founded by Peter Thiel, advised its companies on the morning of March 9 to withdraw their money from SVB. Why? We don't know for sure because neither FF's management nor Thiel are talking about what motivated them. Maybe they misread the Moody's downgrade. Maybe the capital raise spooked them. Maybe they heard some gossip that alarmed them. Or maybe it was nothing other than an excess of caution because they figured no harm would be done.

But Founders Fund is well known and influential, and news of what they had done spread around the Valley at light speed. Within a few hours, a $42 billion run had left SVB in ruins and the FDIC had taken over.

And now for a prediction: As more information unfolds and panic subsides, the FDIC will find out that SVB was not only solvent before the run, but even after it. Everyone will be paid in full and there will be money left over. The FDIC did the right thing regardless, since there's no stopping a run once it gets started, but there was never any good reason for it in the first place.

Mark that to market.

If Peter Thiel is involved, my leading theory until proven otherwise is that SVB did something that annoyed him so he decided to destroy them.

They don't have to have annoyed him at all, he simply needed a victim to demonstrate he could do it.

It's probably giving Thiel too much credit for prescience to think that he foresaw this result.

Bbbut Kevin! Things were done in 2018! And they must have led to this because they were things we didn’t like!

The purpose of analyzing the failure of SVB should be to find out how to avoid future failures, not just to point fingers, still less to say that it was unavoidable - or whatever Kevin is saying. Whether SVB was "solvent" or not according Kevin's or anyone's reckoning a run happened and it was considered systemically dangerous so that the FDIC and the Fed had to intervene. When there is a systemic panic, nothing is safe - this is how major recessions happen.

Whatever regulations existed there were deficiencies if only in application. There are changes that can be made, but there probably won't be any legislation as long as Republicans hold the House - and probably not even if Democrats take over. The finance industry is too strong to allow anything to get done except when there is an actual major collapse.

Kevin brings up more reason to blame the Fed, or more generally to blame relying on the Fed to control the economy. The promises the Fed makes about future interest rates are meaningless if it is supposed to jump into action when inflation rises. And the Fed cannot predict inflation any better than anyone else. Kevin has made a good case that inflation has subsided this time before Fed action could have had any effect. The Fed failed to control inflation in the 70's and 80's, contrary to (the bizarre) general belief.

Quite true. The thing to be vigilant about is another Minsky moment.

I also think it's worth pointing out that EVERYBODY knew interest rates weren't going to stay near zero forever.

I think it's also reasonable to say that people with an elementary understanding of the principles involved would also conclude that the Fed's "we won't be raising rates for a while" is on a MUCH shorter time scale than the maturity date of those long-term bonds.

So uh... yeah, it's still something that the regulation that was removed in 2018 for banks of SVB size would've helped. AFAICT, the deregulation killed the stress test that would've flagged that SVB was too vulnerable to losses on its bonds because it didn't diversify enough.

The FDIC was originally set up so that it could handle bank failures without jeopardizing the whole economy and it did handle a number of them. But there were also regulations, included for example in Glass-Steagall, that restricted what banks could do, and these have been weakened over time. Roger Lowenstein has a good piece in the NY Times on the history of this.

Also banks have continued to get bigger and more dangerous if they fail. The small banks that would have had only insured deposits have continually disappeared.

It doesn’t seem as though SVB was engaged in anything that Glass-Steagall would have prohibited. For example, they weren’t engaged (to my knowledge) in underwriting securities.

They made commercial loans, took in deposits, and bought high-quality assets. But they basically acted like an S&L in the 1980s, hoping that the interest they earned on long-term assets would always be more than what they paid out on short-term deposits. Currently, short-term rates are higher than long-term rates, and higher rates over all tanked the value of the long-term fixed rate bonds they bought two years ago (even though those bonds were very, very secure).

Oops.

(I agree that their heavy dependence on deposits in excess of the FDIC minimum was a big red flag indicating that any kind of bank run would snowball very quickly.)

The extreme dependence on jumbo corporate deposits - really extreme as more typical even on aggressive basis to have 30% core deposits, where they had 3-5% - is also combined with an extreme sector concentration risk aligned also with their lending.

That concentration was a lot of risk alignment and very risk sensitive to change on multiple fronts.

Very atypical

"...since there's no stopping a run once it gets started, ..."

This isn't true, the government could have guaranteed the deposits and loaned SVB enough money to cover the withdrawals. If SVB was clearly solvent this would have been the right thing to do (although perhaps politically unpopular). But unlike Drum I would bet SVB was and is insolvent. They had other loans besides the government bonds. If they managed to lose a small fortune buying government bonds who knows what the rest of their loan book looks like.

Bonds are not loans.

Their core business in lending by all analysis so far indicates perfetly solvent. This was the focus of examination and market prior.

The losses are on the government bond portfolio bought to place unused (not lent out) deposits were hold-to-maturity and paper losses, this was not a trading portfoio, it was a hold portfolio, irrelvant except when faced with the need to do firesale in the face of deposit runs.

Confusing utterly different things will only lead... well to the irrational panic

Bonds are, in fact, loans. It doesn't matter whether you call the paper an IOU, a bond, a promisory note, or a bank deposit, it's a debt transaction in which one party receives money today from the other party in exchange for a promise to repay it with interest at some time in the future.

The most obvious question, which Kevin doesn't ask or answer, is who made money on SVB collapsing?

There is no excuse for a bank not to hedge its long-term assets (in this case, bonds) against its short-term liabilities (in this case, deposits). We’ve known that since the S&L crisis of the 1980s. (Also, Orange County.)

That’s why we have a trillion-dollar interest rate swap market. It’s very, very efficient. Any chucklehead can do it.

The reason SVB didn’t hedge its interest rate mismatch between assets and liabilities is simple: it was greedy.

If SVB had hedged its interest rate mismatch, then the loss it realized from selling bonds would have been largely offset by unwinding its corresponding hedges.

A bank dumping $20 billion of assets at a $2 billion loss is not prudent. It’s desperate.

SVB was also known for chasing deposits at high rates—again, because it was greedy.

Also, the concentration of SVB in a single industry made a bank run far more likely. When you only bank tech, the bursting of a tech bubble means all of your depositors will flee.

The other two banks that failed were similarly concentrated in sectors that experienced a bubble bursting (crypto).

This ain’t rocket science.

+1000

To continue, the purpose of a bank is to earn money by evaluating and taking on credit risk. Ideally, it takes in deposits at floating rates and lends them out at (higher) floating rates, with the spread between the two reflecting the bank’s judgment of what return is needed to mitigate the risk that some of the loans will default, and turning a profit. This is a valuable service indispensable in any economic system. Virtually all commercial banks that engage in prudent lending practices are profitable and successful.

If the bank cannot lend out money on deposit, then excess funds should be parked somewhere safely, without any expectation of return, because the bank hasn’t done anything to earn a return. That safe investment could either be short-term Treasury notes or long-term Treasury bonds hedged (swapped) back to a floating rate.

Any moron can speculate on whether interest rates will increase or decrease. That’s what SVB did, and it lost billions by turning itself from a bank into a casino.

Placing money in US Treasuries is not turning a bank into a casino

Good god, populust sloganeering .... really needs to have some sense.

Placing demand deposits in long-term bonds is simply betting on the shape of the yield curve, no different from placing any other bet at a casino.

It’s how Orange County went bankrupt (except they took the other side of the trade, issuing long-term bonds to invest in short-term bills).

It doesn’t matter that the long-term bonds were of the highest credit quality. An increase in interest rates will reduce the value of a long-term bond far more than the value of a short-term investment, because more of the money contracted to be received is in the future, when that money is worth less.

Here's one possible scenario:

1. I'm a VC with many of my companies banking at SVB.

2. I see that SVB has a classic liability / asset duration mis-match, but is otherwise sound.

3. Me and a few of my pals take big trading positions that will increase in value in the event SVB fails or there is general market instability. These positions don't have to be as crude as a short position in SVB stock. They could short positions in the stock of other regional banks or the purchase of options that would increase in value if market volatility spikes, as it would in the event of a bank run.

4. I generate a bank run by instructing my portfolio companies to withdraw their cash from SVB IMMEDIATELY.

5. I make enormous profits on my trading positions.

6. I demand the FDIC / Feds make all depositors whole, since some of my companies probably still have money there.

7. The FDIC obliges (as it was right to do).

8. My portfolio companies are fine and I've just made (another) fortune.

I'm not a VC and I don't have ANY proof this happened, but it certainly seems like a profitable scheme.

Text should say it's the Q3FY2022 10-Q (not Q4)

Industry superannuation funds in Australia invest in all sorts of assets apart from stocks and bonds: office buildings, mines, toll roads, airports and so on. There are rules limiting the circumstances in which members can withdraw their money, but many people (like me) choose to leave it there even after we become eligible to withdraw it without notice.

I have little doubt that if for some extraordinary reason all the members of a fund entitled to withdraw their accumulated benefits decided to do so at the same time, the fund would be unable to pay out the full entitements immediately. Carrying a massive cash balance just to guard against such an implausible run would be crazy. Moreover I have no doubt that if such an unlikely event ever did happen, the federal government would make sure the fund had access to sufficient new short-term loans to allow it time to sell off assets in an orderly fashion. It would do this to protect the integrity of our superannuation industry.

I can't understand why the US government didn't do the same for SVB, if its financial position was as Kevin describes it. A calm announcement that SVB had a temporary line of credit to allow it to meet an unprecedented panic run would surely have reassured depositors, and perhaps even seen its share price recover.

Hopefully Treasury is thoroughly investigating Thiel's dealings, to see if he benefited from the panic he caused. It would be nice to find out he engaged in some serious short selling of SBV shares, never anticipating that his panic would cause it to actually collapse.

Whoa! The Federal Funds chart shows the first rate hike in 2022 as occurring in March (actually took effect on March 17, 2022). The Chief Risk Officer left on April 29, 2022! THE question of interest is whether that departure might have had any connection to SVB's choosing not to hedge their $100 billion long Treasury position when the Fed had clearly entered a major tightening phase starting in March.

Given that until last week's events the Fed had committed to yet more rate hikes, SVB's financial position would have only continued to deteriorate in the absence of hedging. Their position would not have magically improved.

I am not sure, though I suspect that SVB would not benefit from the subsequent fall in long-term rates. My guess would be that their treasuries would have been sold as quickly as possible after the bank was shuttered.

The bank should have hedged its long-term assets when it acquired them—because hedges then were cheap. It’s too late after interest rates begin rising—then hedges become expensive.

It would have been better if the bank had simply matched demand deposits with short term paper.

I read that hedge funds would offer a 60-80% payout to businesses to give up their deposits. With the government bailout, which might be paid back once all assets are found, it's the same hedge funds that will be screwed.

The Line Goes Up Club and their Pet Bank had a falling out? Not buying it. There's a short somewhere and somebody is cackling.

Now for another truism: "The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent"

No bank could have survived that type of bank run. They'd be losing money for a few quarters or more--bad for investors. Survivable, unless they had to cash in all their long term t-bills.

As for hedging....the Frontline show, Age of Easy Money, one of the experts said everything is bad now, soo nothing really to use as a hedge. Bubble bubble toil and trouble.

At the heart of SVB's failure, we keep telling ourselves, is a unique case. But, what if it fundamentally isn't?

What if there are dozens of banks big and small who have poorly weighted portfolios on account of a decade+ of cheap money, putting them in jeopardy of inadequate liquidity?

What if the structure of Finance has shifted under the feet of bankers, by way of the Fed, and they're too slow to catch up with the new reality? I'd like to see you randomly choose a couple of banks and go through their portfolios. You can't know the answer if you're not looking.

With the actions of FDIC/Fed over the last seven days, it sure looks like they've gone through a bunch of banks and have come to the conclusion that this as a major black swan risk that needs to be quelled at any cost.

Also, I thought you had lost interest in this topic?

There is no need for What Ifs, the data is quite available. In fact Martin Wolf in FT had an analysis of compratives.

Drum's overall post is quite right.

Additionally several days ago a comparative in FT: https://www.ft.com/content/84dc06d5-2cb7-4c0c-b0a2-5b2ab76e60eb in Unhedged.

Data is not lacking, your personal lack of knowledge aside.

The reason such as Unhedged etc are not seeing general crisis from a rational numbers PoV as sans panic there is in fact no reason for this. None.

Yes, my lack of personal knowledge is exactly why I'm asking the question. But note that in your linked article, Armstrong and Wu are hedging:

Separately, Black Rock's Larry Fink made the point:

See, what's happening to Credit Suisse suggests, to me, that SVB's unique problem was actually a wider issue, that the focus on what made SVB unique is an error in judgement of what the true risks are to banks -- adjusted leverage ratios and cash on hand.

What do you think?

SVB was clearly insolvent.

Kevins claim that the bank was never insolvent appears to rest on the assumption that if only the banks counterparties had never exercised payment on the liabilities, the bank would have been solvent.

We have redefined solvency into a meaningless term if it means that assets are greater than liabilities assuming liabilities wont need to ever be paid out. With this definition, its impossible to be insolvent.

Kevins post has many true facts in it, but it appears to rank misinformation/propaganda.

An insolvent bank with a massive duration mismatch and no risk management approach failed. But because the rating agencies and auditors failed to publicly identify the risk, we see lots of people throwing up their hands and insisting that nothing could have been done. Maybe we can blame a few rogue depositors instead?

Assigning the blame in this way makes it easier to provide bail outs, prevent regulatory enhancements and look under the hood at the rating agencies and auditors who failed once again.

Wow! Inflation went out of control in 2021 and then in March of 2022 interest rates finally increased. In April of 2022 annual inflation had already reached ~7%. The interest rate risk was baked in even in 2021? Talks to replace the chief risk officer at SVB in early 2022 then make a great deal of sense. Even by early 2022 it would have been transparently obvious that SVB would soon have deeply embedded financial risk. Calling it a liquidity problem and ignoring the fact that treasuries are the most liquid investment available then becomes a fairly hollow argument when it is in fact more a solvency problem (i.e., having marked to market losses of ~ $20 billion).

I just completed an online Money and Banking course. Given my level of understanding, the problems that emerged at SVB do not even demonstrate remedial competency in banking management. Even with my kindergarten Banking 101 knowledge the errors that were made are self-apparently obvious.

Pingback: Weekend link dump for March 19 – Off the Kuff

Pingback: Conventional narratives get set in stone almost instantly these days. Why? – Kevin Drum