I've mentioned several times that the Fed's aggressive interest rate hikes haven't yet had an effect on inflation, which has been declining on its own. The reason is that it takes time for the impulse of an interest rate hike to work its way into the economy and produce an impulse in the inflation rate.

But on average, how long does this take? Fifty years ago Milton Friedman popularized the idea of "long and variable lags," which suggests we don't really know for sure. But there's been a ton of research about this since then, which means we can at least hazard a guess or two. This will take a while, so buckle in.

Our first problem is that a great deal of the research looks at how long it takes interest rate changes to have their greatest effect on inflation. The most common guess is 18-36 months. This is suggestive that interest rates have very little impact in their first year, but no more than that. What we really want is research that tells us how long it takes for an interest rate hike to have a noticeable effect on inflation.

Here are a few comments on that:

- Esther George, Kansas City Fed President: "We don't know exactly. I think typically, we've thought about 6 to 12 months of lag in that."

- Nate DiCamillo, Quartz economic reporter: "Part of the reason why the Fed’s rate hikes haven’t had more of an effect is that they take about six to nine months to work their way through the economy."

- Raphael Bostic, President of the Atlanta Fed: "A large body of research tells us it can take 18 months to two years or more for tighter monetary policy to materially affect inflation."

- James Cloyne, then of the Bank of England, and Patrick Hürtgen of Germany’s Bundesbank: "In the U.K., a 1 percentage-point increase in the policy rate reduces output by 0.6% and inflation by up to 1 percentage point after two to three years."

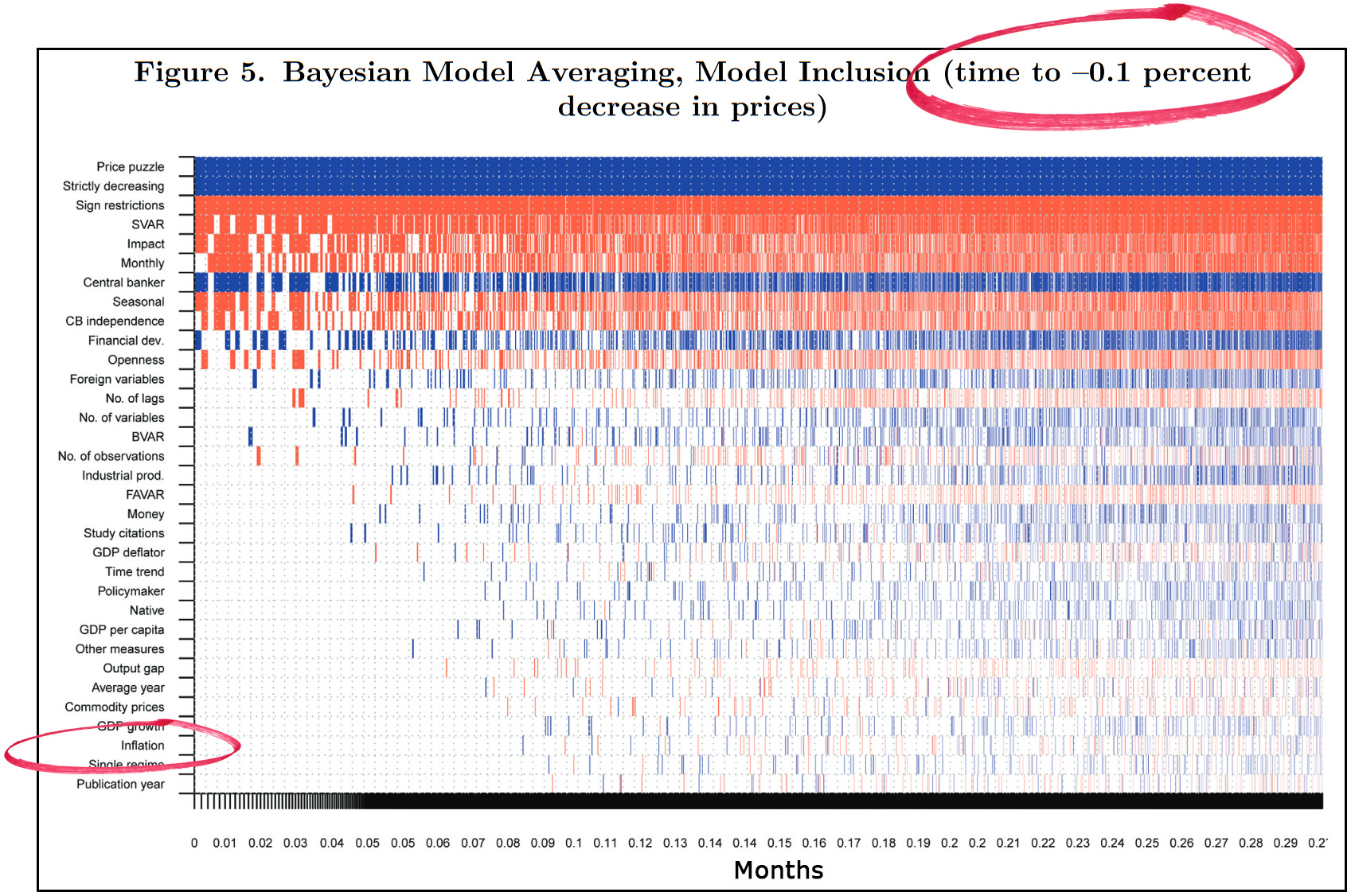

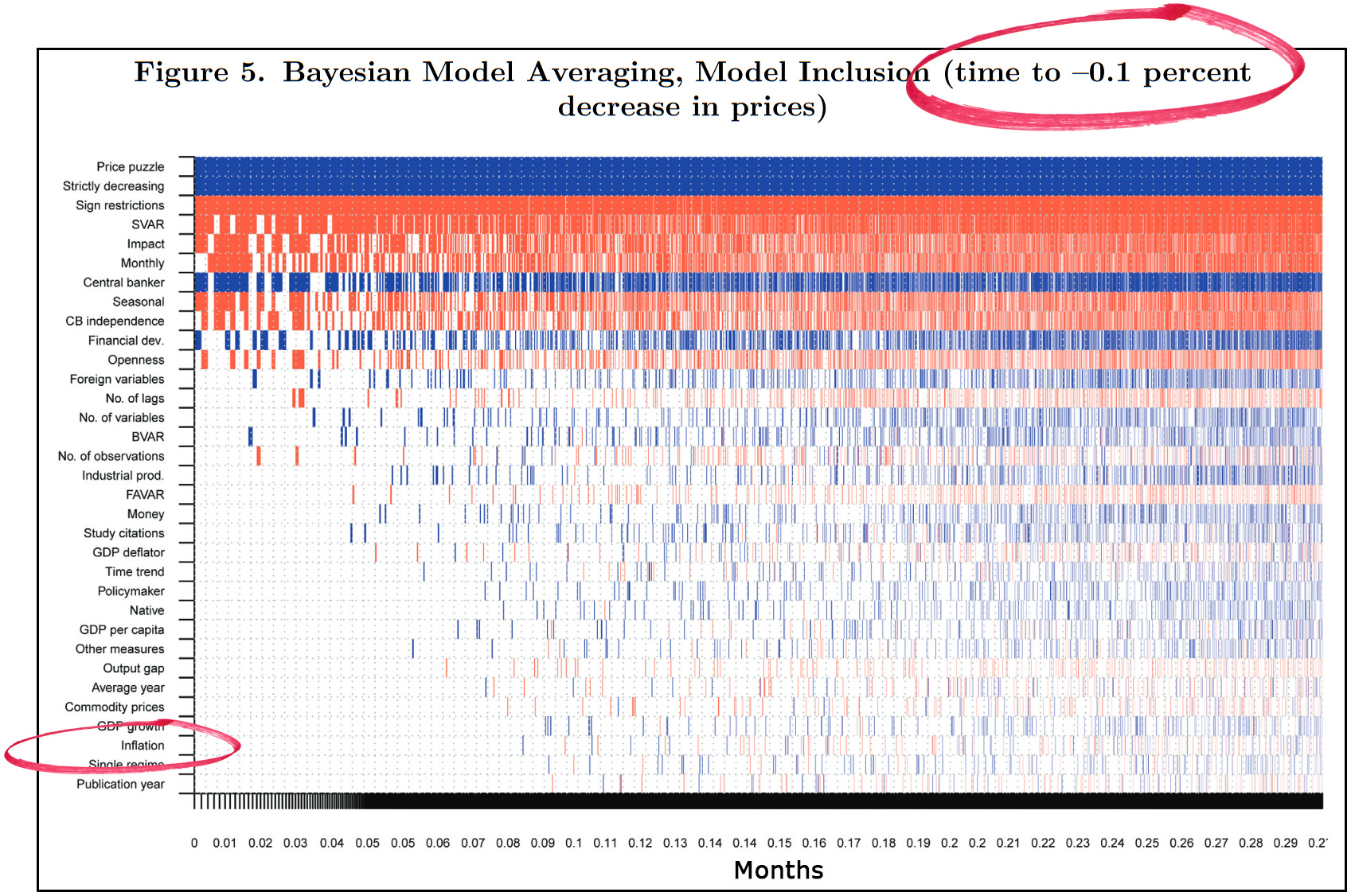

Taken together, these suggest that interest rate hikes start to have an effect on inflation in about a year or so. But I have one more study to add to this, and it's the most interesting of all. It's a meta-study from Tomas Havranek and Marek Rusnak of the Czech central bank and it examines research about monetary policy changes in dozens of countries over the past few decades. It suggests that the maximum impact of rate hikes takes 3-4 years to materialize in the US. But now take a look at something else. First I'm going to show you the whole chart even though it's illegible at this size:

For now, just take a look at the two things I've circled. First, this is a measure of how long it takes for a rate hike of 1% to produce an inflation response of -0.1%. In other words, how long it takes before you get the first hint of lower inflation.

For now, just take a look at the two things I've circled. First, this is a measure of how long it takes for a rate hike of 1% to produce an inflation response of -0.1%. In other words, how long it takes before you get the first hint of lower inflation.

Second, look at the lower circle. Out of all the things that monetary policy affects, inflation is the very last. Inflation reacts very slowly to rate hikes.

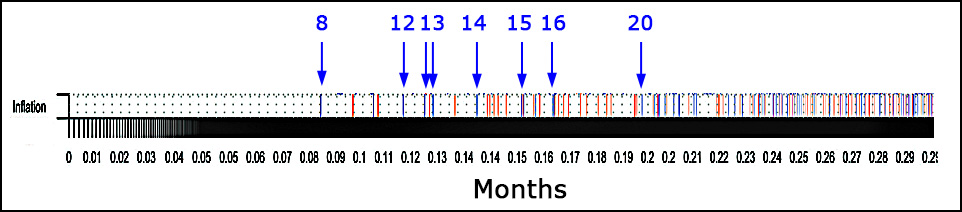

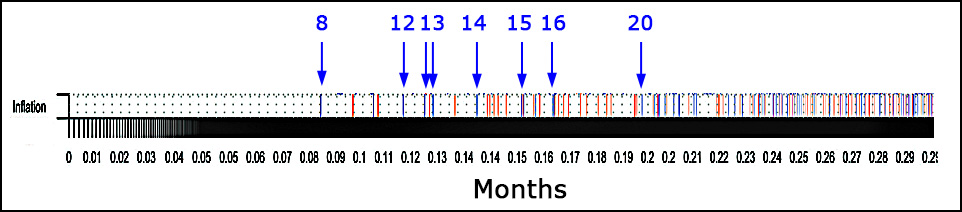

Now let's zoom in on inflation and see what it says:

This is still not the most legible graph in the world, but it does the job. The blue lines represent monetary episodes that produced a positive response—that is, where a rate hike produced the expected reduction in inflation. The earliest response was 8 months and every other episode took at least 12 months to have an effect on inflation.

This is still not the most legible graph in the world, but it does the job. The blue lines represent monetary episodes that produced a positive response—that is, where a rate hike produced the expected reduction in inflation. The earliest response was 8 months and every other episode took at least 12 months to have an effect on inflation.

Bottom line: Except in the most extraordinary circumstances, rate hikes take around nine months to have an effect, and 15 months is probably more likely.

In our current case this doesn't really matter. The earliest date for serious Fed hikes is May 2022 and nine months takes us out to February 2023. It's an almost sure thing that the Fed's actions have had no effect on inflation yet, and probably won't for another three months—maybe longer.

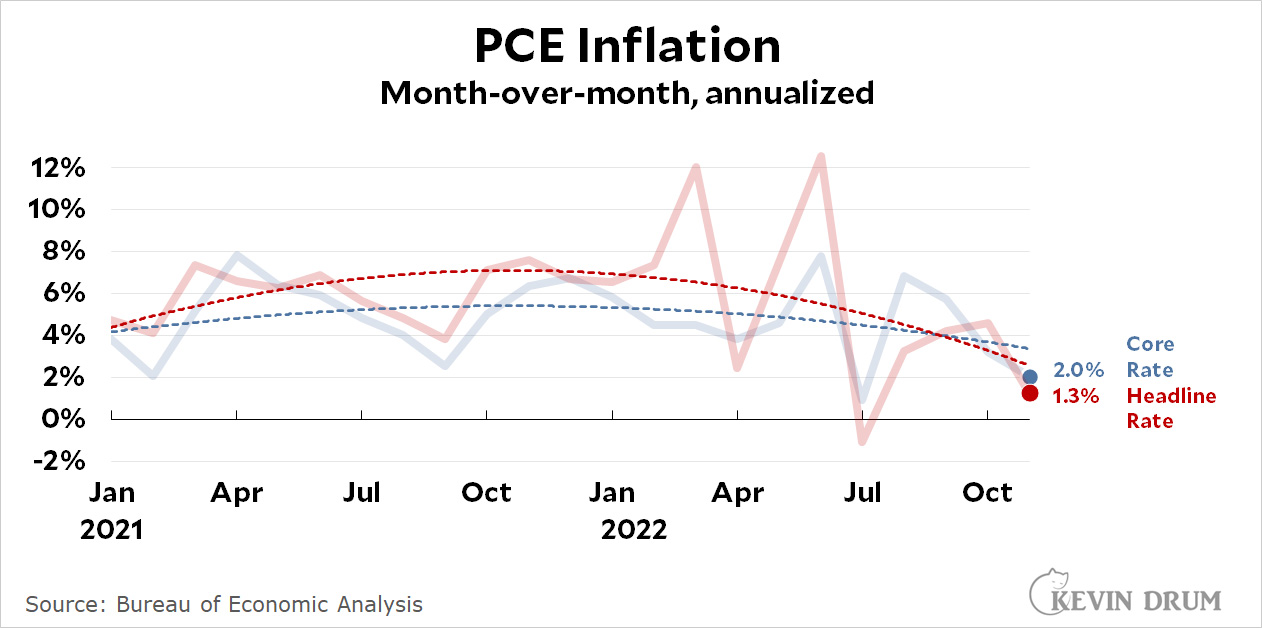

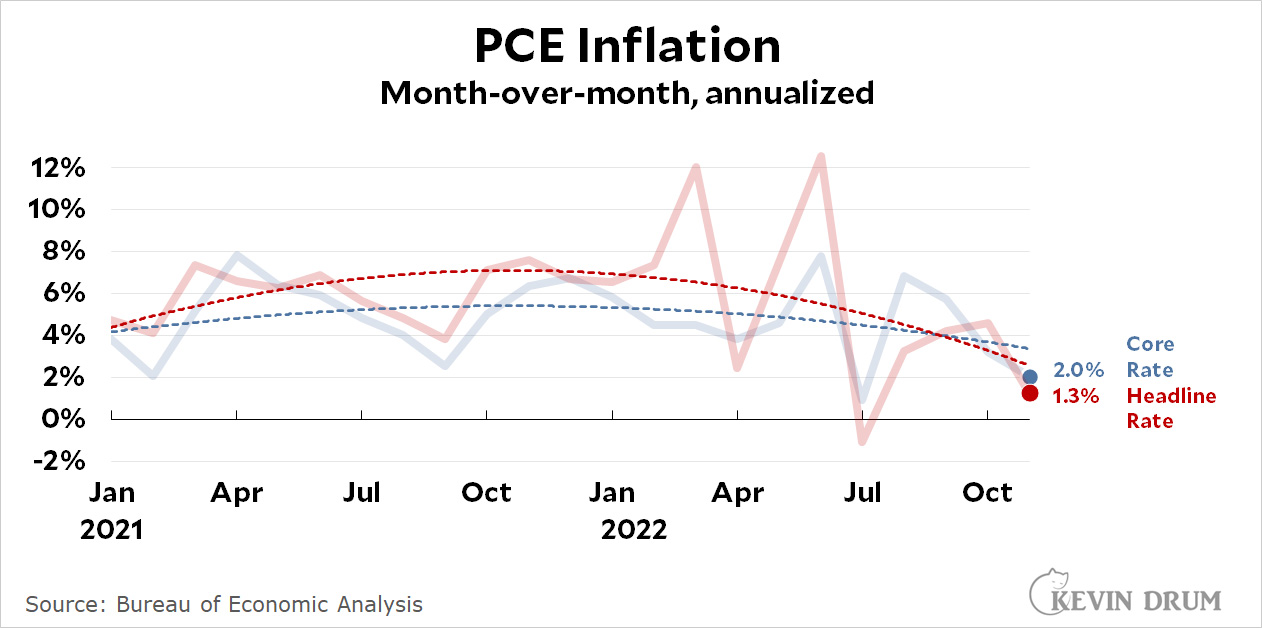

And yet, during that time core inflation has plummeted:

What caused this? My take is here (supply chain problems, stimulus, rents, and savings) but it doesn't matter much if you agree with me. The one thing we can say with high confidence is that it hasn't been the result of interest rate hikes.

What caused this? My take is here (supply chain problems, stimulus, rents, and savings) but it doesn't matter much if you agree with me. The one thing we can say with high confidence is that it hasn't been the result of interest rate hikes.

However, interest rate hikes generally affect economic growth sooner than they affect inflation. In fact, low economic growth is one of the channels used by rate hikes to influence inflation. So there's a good chance that the Fed has already hurt the economy and will continue to hurt it even worse next year, all the while affecting the inflation rate—which had already come down by itself—only much later, when we no longer care about it.

Worst. Fed. Ever.

Purchases of durable goods have gone through big swings since the start of the pandemic, and the trendline decline this year is mostly an artifact of huge growth in January. Take that one month away and the trend is actually up. The much larger services sector is less volatile but has been declining a bit all year.

Purchases of durable goods have gone through big swings since the start of the pandemic, and the trendline decline this year is mostly an artifact of huge growth in January. Take that one month away and the trend is actually up. The much larger services sector is less volatile but has been declining a bit all year. It's been running at about 2.4% since mid-2021, almost identical to the 2.5% growth rate before the pandemic. As you can see, the November figure was very low but appears to be mostly noise. Generally speaking, consumer spending has stayed pretty steady so far even as wages have dropped and savings have been used up.

It's been running at about 2.4% since mid-2021, almost identical to the 2.5% growth rate before the pandemic. As you can see, the November figure was very low but appears to be mostly noise. Generally speaking, consumer spending has stayed pretty steady so far even as wages have dropped and savings have been used up.