Over at the American Prospect, David Dayen argues that Democrats need to deliver the goods if we want people to vote for us. That is, we need to adopt a deliberate and sustained policy of "deliverism." The problem is that we think too small. Take Obamacare, for example:

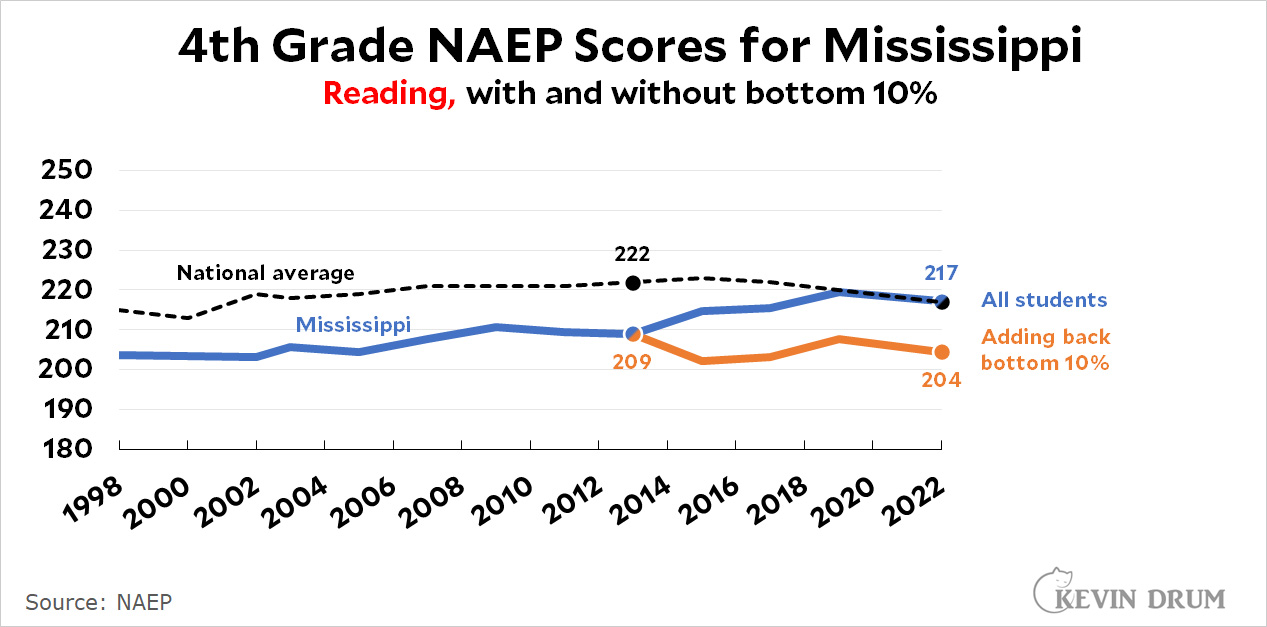

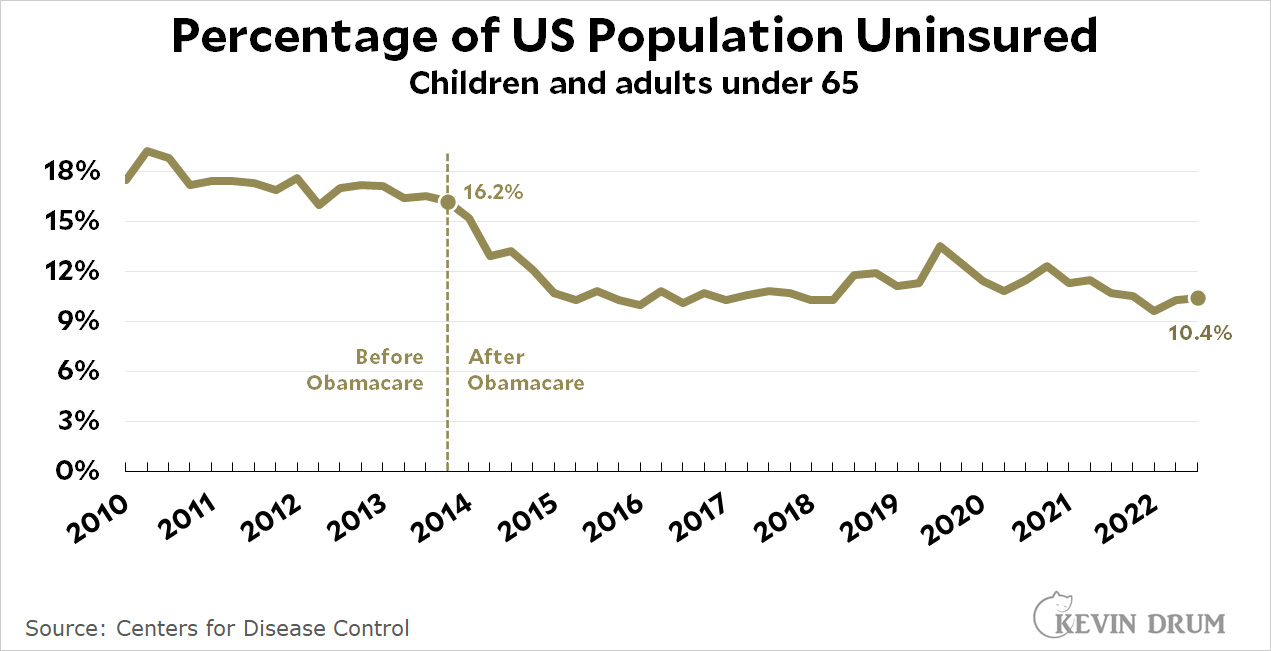

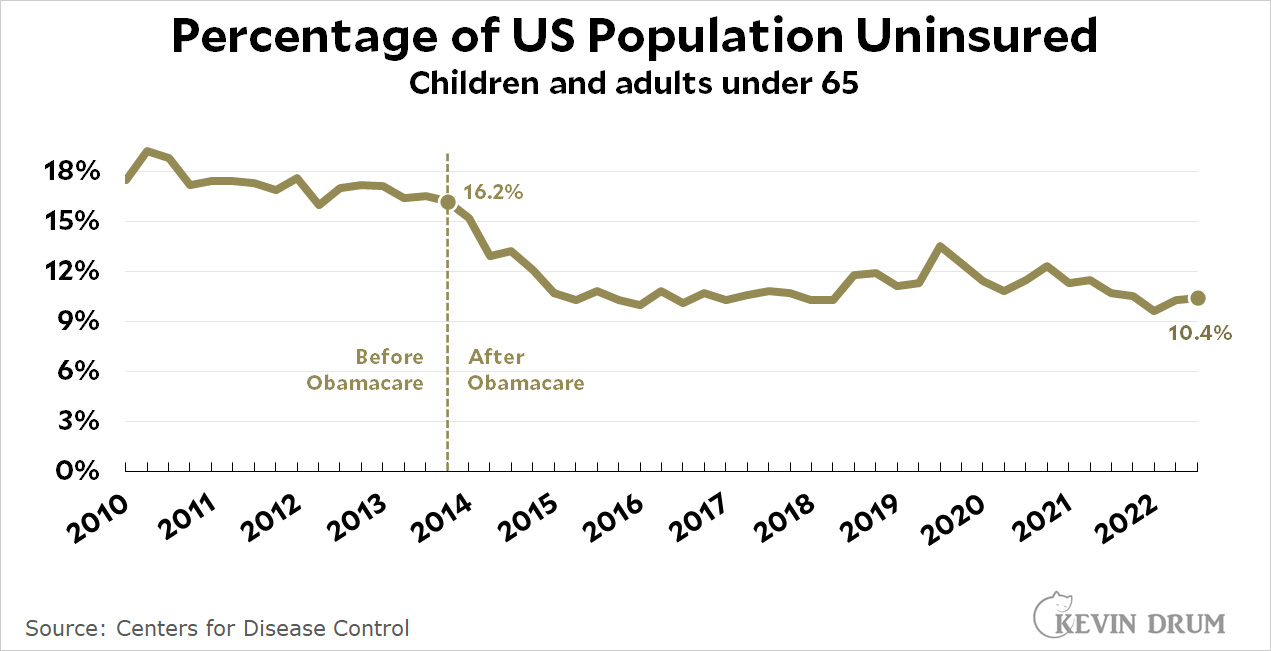

First, the goal of Obamacare was to insure more people, and it did. Roughly 85 percent of Americans had health insurance in 2008. Today, it’s about 90 percent.

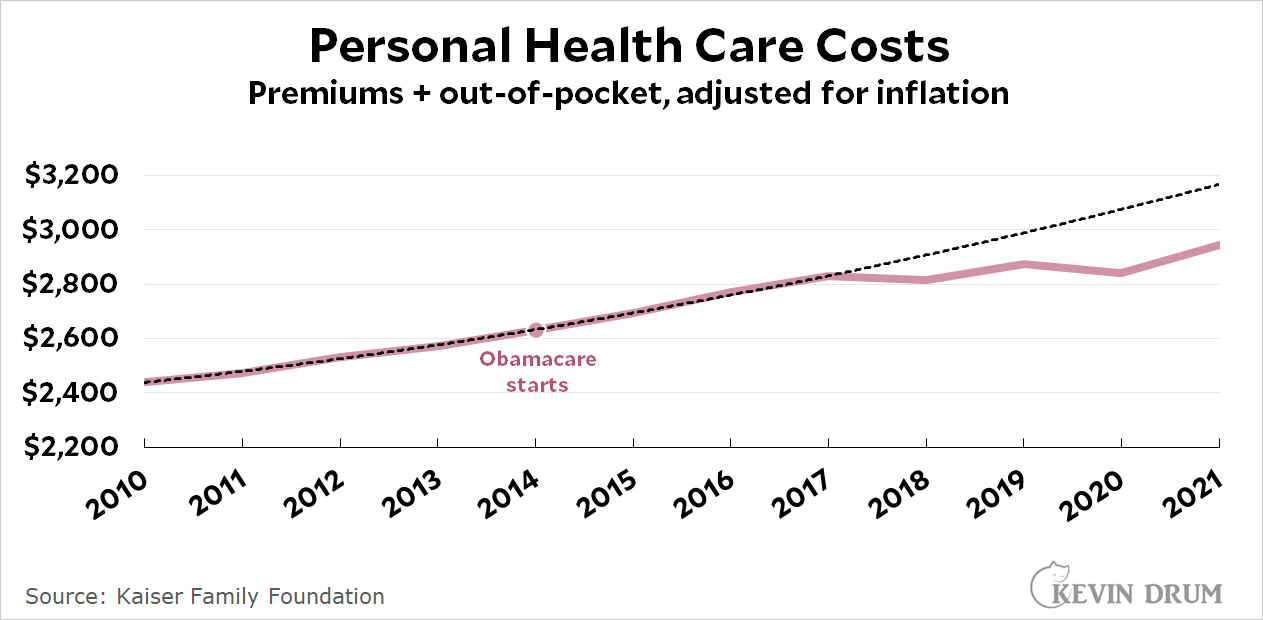

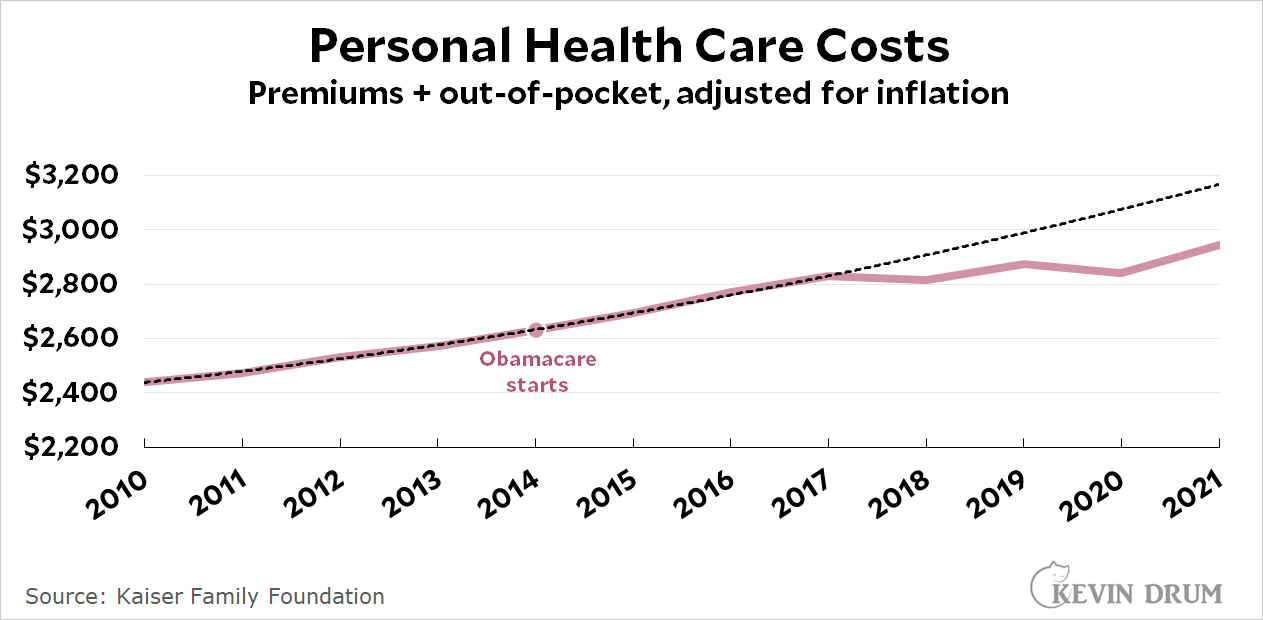

....In 2009, the average medical cost for a family of four was $15,609. Today, it’s $30,260. That’s almost the cost of a new car in health care costs, every single year. In other words, 85 percent of potential voters have the same or a worse experience with health care today, versus 5 percent who gained insurance. It’s hard to call that a net economic improvement in the lives of most voters.

This isn't quite fair. David is right about the uninsurance rate but off by quite a bit when it comes to how much people spend on health insurance:

The uninsured rate has dropped about six points under Obamacare, which represents something like 15 million people. But when you analyze overall health care spending, what matters isn't the total cost of health care but how much you have to personally shell out from your own paycheck. That's out-of-pocket deductibles plus your share of premiums, and it comes to about $3,000 these days. As you can see, Obamacare really did help to push this down. Most people are having a better experience with health care.

The uninsured rate has dropped about six points under Obamacare, which represents something like 15 million people. But when you analyze overall health care spending, what matters isn't the total cost of health care but how much you have to personally shell out from your own paycheck. That's out-of-pocket deductibles plus your share of premiums, and it comes to about $3,000 these days. As you can see, Obamacare really did help to push this down. Most people are having a better experience with health care.

Nonetheless, there's no denying it: six points in the uninsurance rate isn't a lot. And while the growth of health care costs has slowed for the average person, actual costs are still going up. Hardly anyone is going to notice that, and they certainly aren't going to base their vote on it.

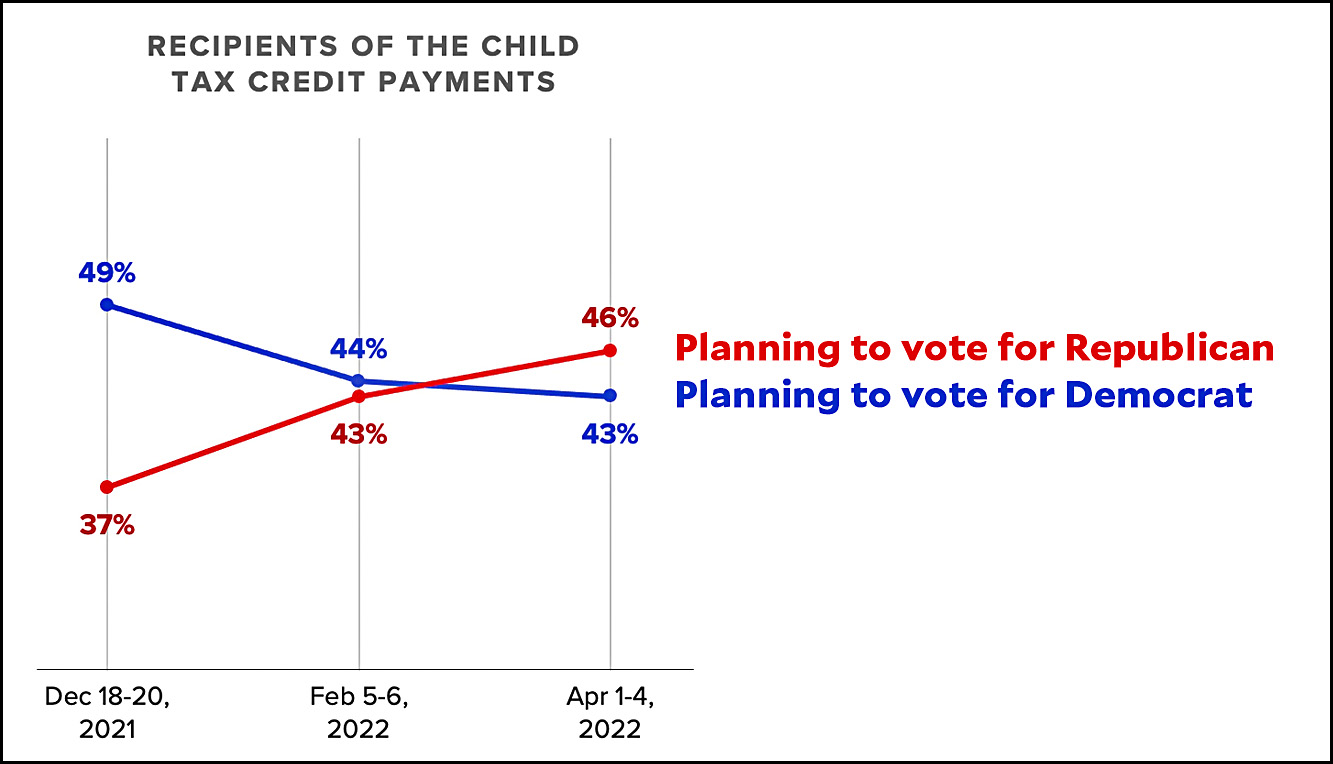

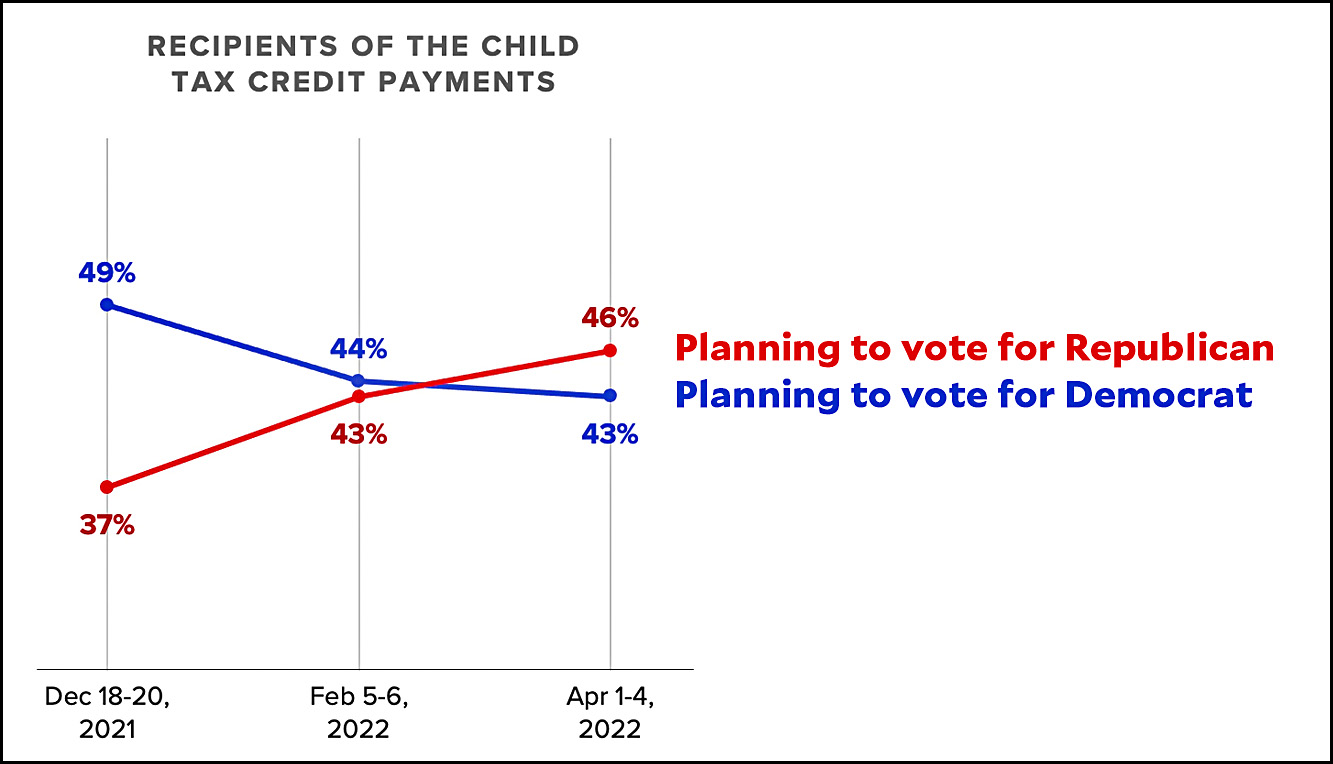

The other problem, as David says, is that even if a program is big enough to be noticeable it isn't much good if it's temporary. Here's a fascinating bit of polling about the Child Tax Credit included in the American Rescue Act, which was quite large and noticeable:

I'd be cautious about inferring causality from a very few data points like this, but what it suggests is that people who received the CTC liked it and gave Democrats credit for it. In late 2021, 49% planned to vote for a Democrat for Congress. A month later the CTC expired and the Democratic vote went down to 44%. A couple of months later it was a point further down. It's hard to say if Democrats got any credit for this. It's quite possible that they lost more support for "taking it away" than they got in the first place for starting it up.

I'd be cautious about inferring causality from a very few data points like this, but what it suggests is that people who received the CTC liked it and gave Democrats credit for it. In late 2021, 49% planned to vote for a Democrat for Congress. A month later the CTC expired and the Democratic vote went down to 44%. A couple of months later it was a point further down. It's hard to say if Democrats got any credit for this. It's quite possible that they lost more support for "taking it away" than they got in the first place for starting it up.

So what to do? The problem, I think, is that there aren't any programs left that are big enough to really get people's attention. Big early economic programs—Social Security, unemployment insurance, Medicare, Medicaid—as well as big early social programs—the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, Americans with Disabilities—got people's attention because they started from nothing and then kept growing in importance year after year. Aside from genuine national health care, there's really nothing left like that. Here are David's suggestions:

Democrats could reverse their toxic image in many parts of the country by reversing policy choices on subjects like NAFTA, deregulation, and banking consolidation, which have helped hollow out the middle class for decades.¹

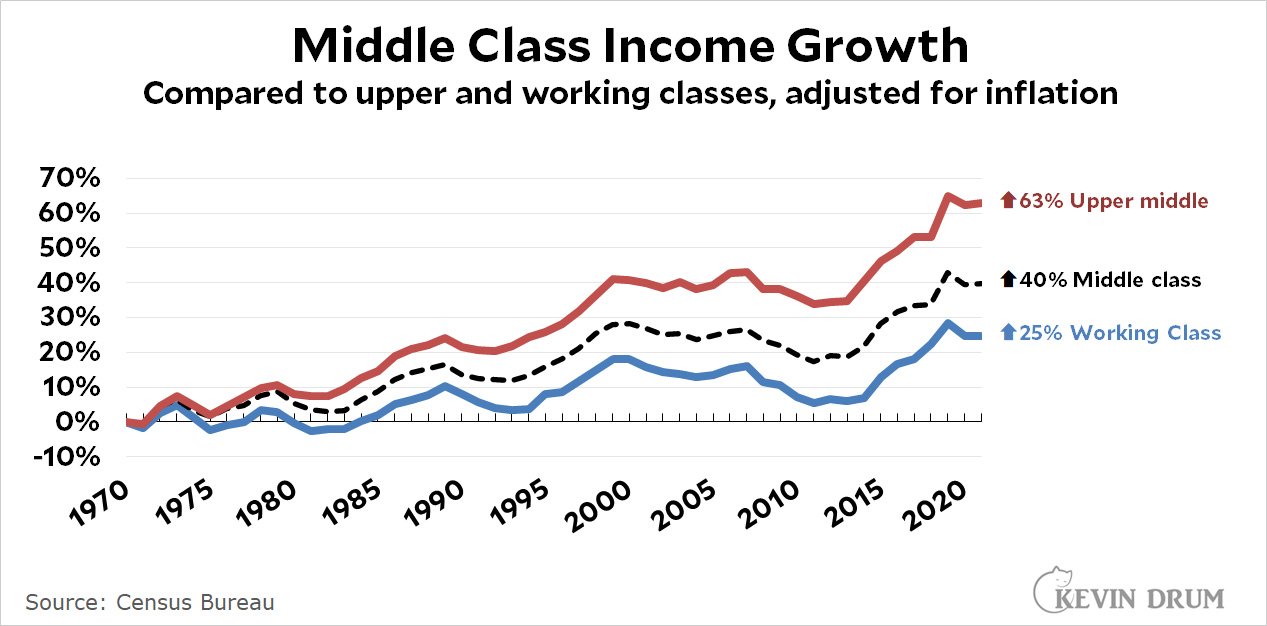

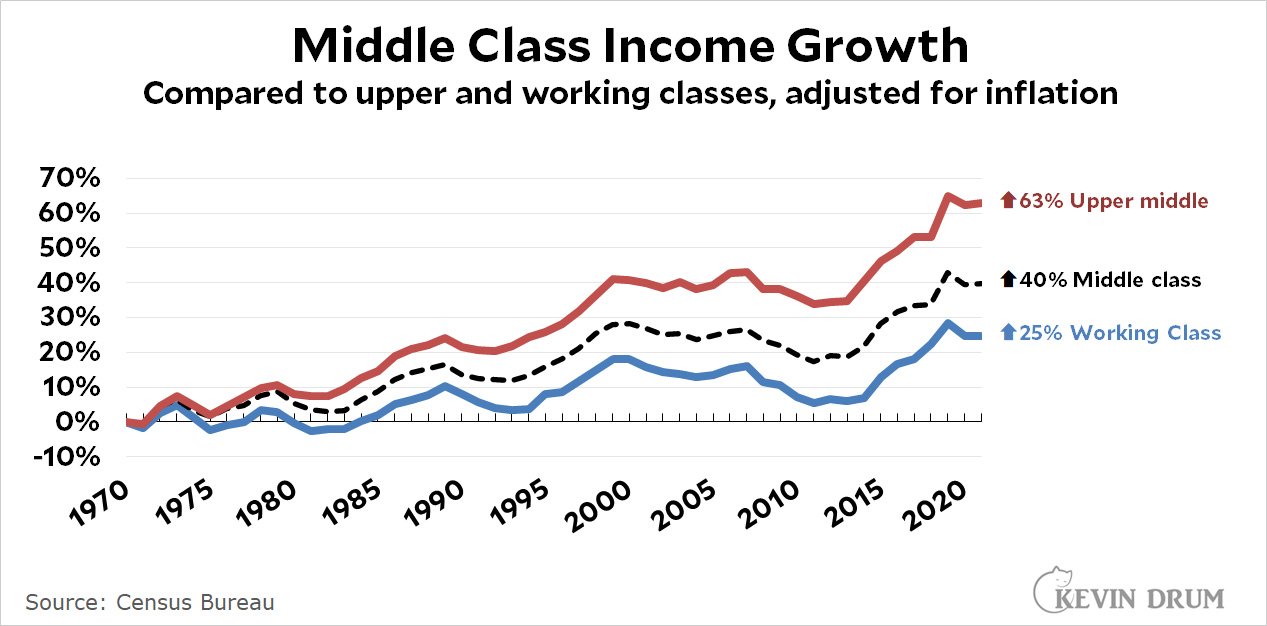

Well. Maybe. But those don't frankly seem like things that most people even care much about, let alone things that would move the voting needle much. As for "hollowing out" the middle class, it just ain't so:

Over the past half century, middle-class incomes have grown 40%. That's more than working-class incomes and less than upper-middle incomes. To the extent that people have moved around, it's mostly working-class folks moving up into the middle class and middle-class folks moving up into the upper middle.

Over the past half century, middle-class incomes have grown 40%. That's more than working-class incomes and less than upper-middle incomes. To the extent that people have moved around, it's mostly working-class folks moving up into the middle class and middle-class folks moving up into the upper middle.

This is the problem right now—if you want to call it a problem at all. The typical middle-class household earns about $70,000 per year, and it's hard to get the torches and pitchforks going among a populace so comfortable.

To an extent, the problem here is less one of "deliverism" and more one of catastrophism. We Democrats insist on an endless message of economic doom and gloom even though all the evidence in the world suggests that most Americans are fairly well off, fairly satisfied with life, and certainly not ready to revolt. Sure, deliverism works only if it's big and noticeable, but it also works only if voters feel a desperate need for it. Right now very few do. This is why social issues dominate the political landscape and probably will for quite a while.

¹As an aside, I'd add long-term nursing care to this list. It's pretty sizeable and it's a very noticeable problem for a lot of people. Aside from national health care, I'd guess that it's about second on the list of things Democrats could deliver that would really make an impression—assuming of course, that we're able to pass something simple, blunt, and comprehensive. That's what it takes.

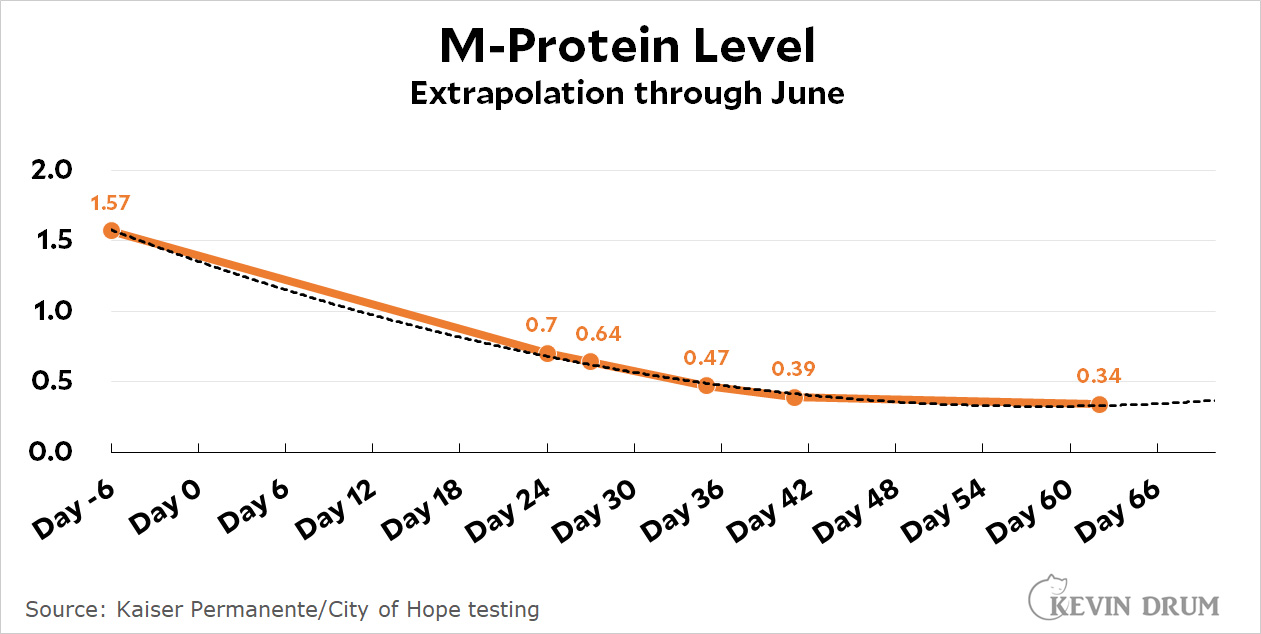

This is a "partial response," and for all practical purposes it means the treatment didn't work. There's a good chance it will keep me chemo-free for a few months or a year, but that's about it.

This is a "partial response," and for all practical purposes it means the treatment didn't work. There's a good chance it will keep me chemo-free for a few months or a year, but that's about it.