Very pretty rainbow(s) over our house to end the day. I guess that's one good thing about endless rainshowers.

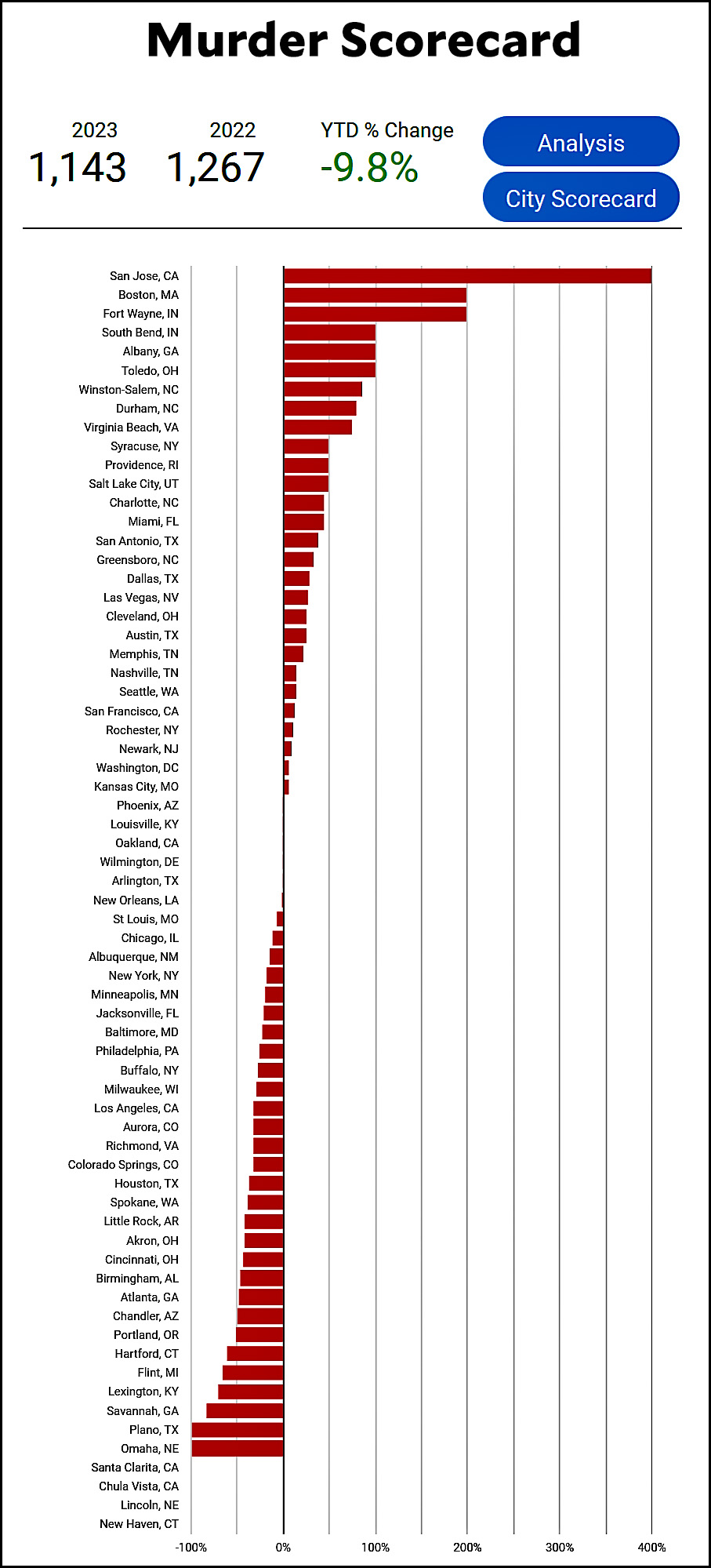

Raw data: Murders are down 10% so far in 2023

According to Datalytics, here's how things look on the homicide front so far in 2023:

Down 10% so far! And that's on top of last year's 5% decline. This isn't enough to make up for the 30% increase during the pandemic, but we're getting there.

Down 10% so far! And that's on top of last year's 5% decline. This isn't enough to make up for the 30% increase during the pandemic, but we're getting there.

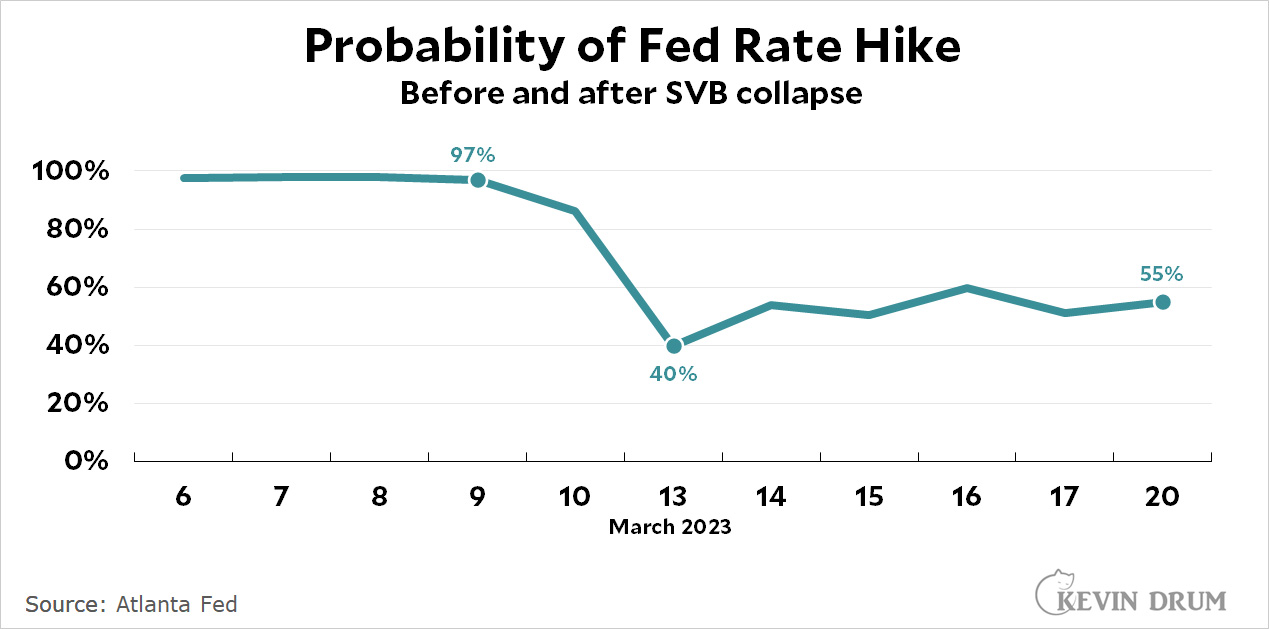

There’s a 50-50 chance of a Fed rate hike tomorrow

Is the Fed going to raise rates tomorrow? According to the Atlanta Fed's prediction tool, the answer is maybe:

Before the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, the probability of a rate hike was 97%, a virtual certainty. After the collapse, that probability dropped to 40% and currently stands at 55%.

Before the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, the probability of a rate hike was 97%, a virtual certainty. After the collapse, that probability dropped to 40% and currently stands at 55%.

Place your bets.

POSTSCRIPT: Needless to say, I don't think the Fed should raise rates. But then, I didn't think they should keep raising rates even before the collapse of SVB.

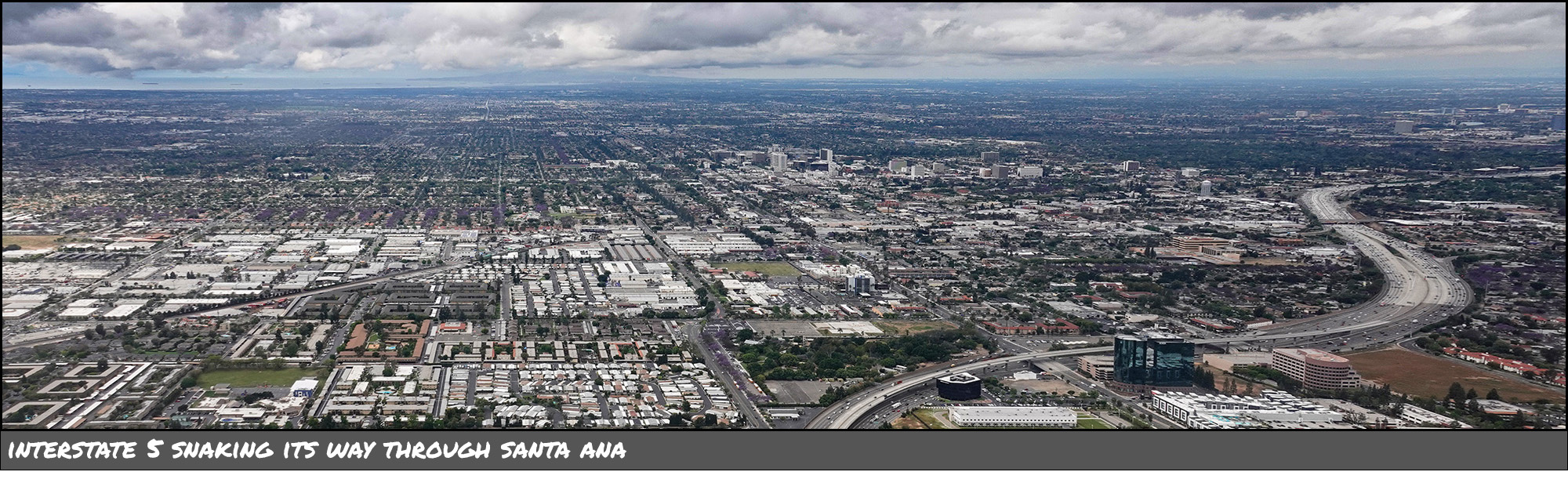

Lunchtime Photo

Narratives of doom get set in stone almost instantly these days. Why?

Over the past year or two I've commented on three conventional narratives that strike me as dead wrong:

- The Afghanistan withdrawal was a disaster.

- The CDC's response to COVID-19 was atrocious.

- Silicon Valley Bank was a time bomb waiting to go off.

The common thread for all of these was an almost instant desire to find catastrophe whether it existed or not. The Afghanistan and SVB narratives literally coalesced within a day. The CDC narrative took a little longer, but not much.

Now, the usual thing at this point would be to blame social media for speeding up our expectations. We want answers now, and when a disaster is only a few hours old there are no answers available except the most obvious ones. And the most obvious ones are tales of error.

But this still wouldn't be a problem except for the next step: conventional narratives freeze in stone almost instantly nowadays. Nothing about social media is obviously to blame for this. But whatever the cause, neither the media nor anyone else seems willing to back off and reassess things as more evidence becomes available.

Some of this is political. The Afghanistan withdrawal, for example, was literally only a disaster during its first four or five hours. The rest of it went reasonably well, and in the end more than 100,000 people were airlifted out. But Republicans had a vested interest in making it look bad, and that affected the press coverage, which was relentlessly negative the entire time.

That said, the three narratives I mention above are entirely bipartisan. Both Democrats and Republicans alike promote all of them. Politics affects some narratives, obviously, but it's not the whole answer.

But what is? I think it's mostly that Americans have become addicted to doom. Any reasonable read of the evidence suggests that things have been going fairly well for most people over the past couple of decades, but it doesn't matter. We're all convinced that things are far worse than they really are. And once your mind is caught in this frame, narratives of catastrophe will always find a friendly home.

We are all doomscrollers now. But if things are actually going fairly well, why?

CDC critics should turn their bazookas on Donald Trump instead

The New York Times reports today on life inside the CDC during the early days of the COVID pandemic. In early March 2020, a bunch of young CDC scientists gathered in a small park across the street from headquarters to discuss whether COVID could be transmitted by people who showed no signs of infection. And if it could, why was the public not being told?

To the scientists gathered outside, trainees in the agency’s vaunted Epidemic Intelligence Service, the implication was clear: C.D.C. leaders realized that the virus was being spread not just by people who were coughing and sneezing, but also by people who were not visibly ill. But the agency had not yet warned the public.

....It was an extraordinarily difficult time even for veteran scientists at the agency, said Dr. Anne Schuchat, the C.D.C.’s principal deputy director until her retirement in May 2021. If they were silent about the risks to the public, it was only because government researchers were muzzled by the Trump administration, she said. But “most of the media was vilifying the agency.”

....The first big shock came in February 2020, when the Trump administration reprimanded Dr. Nancy Messonnier, a senior C.D.C. official, for warning Americans to prepare for a pandemic.

....In Honolulu, where [Dr. Daniel Wozniczka] was deployed, only one infected person had the symptoms the C.D.C. had identified early on....As Dr. Wozniczka became increasingly alarmed, Dr. Kitsutani encouraged him to share his concerns with superiors in Atlanta.

When Dr. Wozniczka returned to Atlanta, he realized that the possibility of asymptomatic transmission was a surprise to no one. All through February, agency scientists had reviewed the increasingly compelling evidence, and data from the C.D.C.’s own investigation of residents at nursing homes in Seattle in early March confirmed it.

A while back I think I figured that Donald Trump had been responsible for maybe 100,000 extra COVID deaths all by himself. I think I might have to revise that estimate upward.

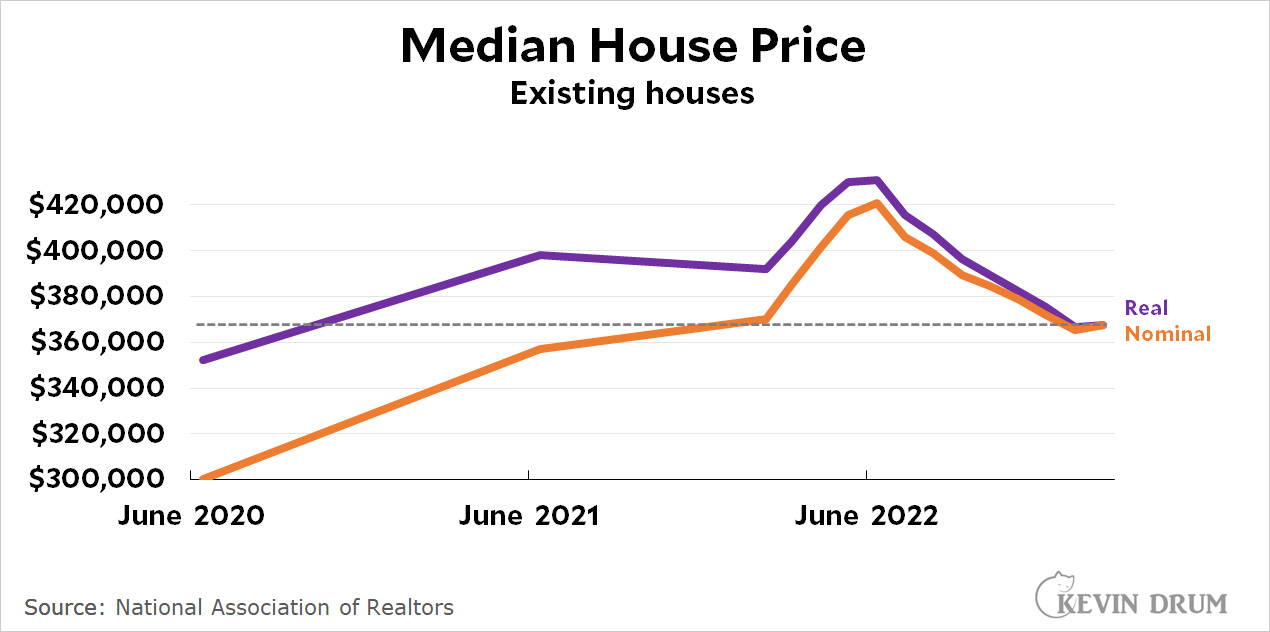

House prices stabilized in February

The Wall Street Journal says that in February home prices fell for the first time in 11 years. That's sort of true, but not really:

February was the first time in 11 years that home prices fell if you look at year-over-year figures and don't adjust for inflation. But if you just chart real home prices, they've been declining since last June. They're now down to the level of two years ago.

February was the first time in 11 years that home prices fell if you look at year-over-year figures and don't adjust for inflation. But if you just chart real home prices, they've been declining since last June. They're now down to the level of two years ago.

Education, not cities, is the key to productivity growth

Eric Levitz writes in New York about America's housing crisis:

The scale of our folly only becomes clear when the second-order effects of the housing crisis are brought into view. The most productive and economically vibrant parts of the U.S. are also the places where housing supply has lagged most egregiously behind demand....According to one 2019 study from economists at the University of Chicago and UC Berkeley, if New York City, San Jose, and San Francisco loosened zoning restrictions that forbid high-density housing construction, America’s total gross domestic product would increase by 9 percent. Put differently, average annual earnings in the U.S. would rise by roughly $8,755.

If we merely loosened zoning restrictions in two places, average pay nationwide would increase $8,755? That seems a little unlikely.

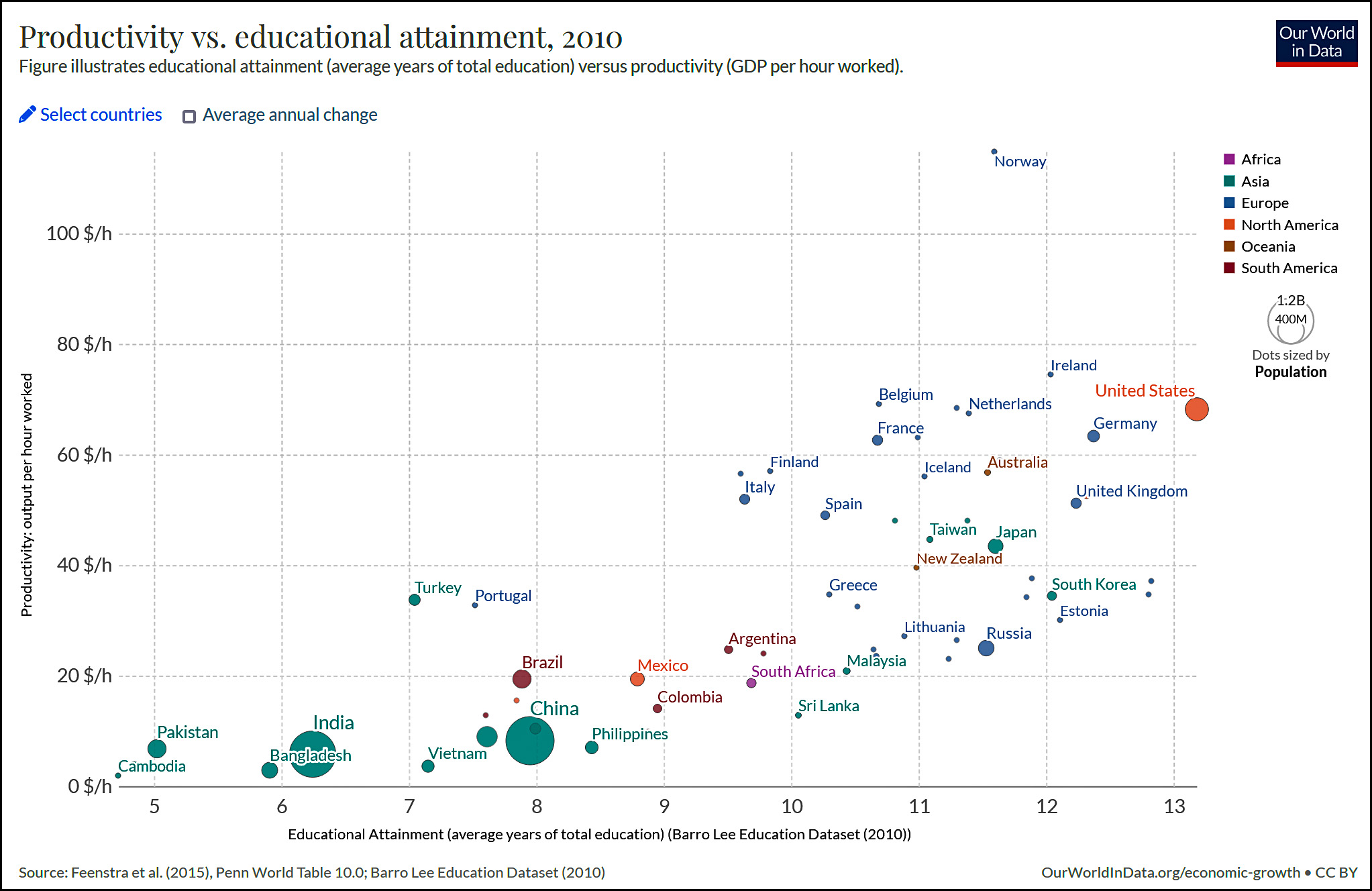

More generally, I'm very, very skeptical of this whole notion that increasing the population of our biggest cities would automatically turbocharge the economy. After all, Africa, Asia, and South America are chock full of megacities, but it's Europe, Australia, and North America that are the economic leaders of the world.

So let's take a look at this. For starters, here are quotes from a couple of papers about the productivity advantages of big cities:

In line with the previous literature, the analysis confirms that city productivity tends to increase with city size; doubling city size is found to be associated with an increase in productivity of between two and five percent.

The metropolitan labor market—defined as the actual number of jobs in the metropolitan area reached in less than a 1-hour commute—is almost twice in size in a U.S. city with a workforce twice the size.

The first paper tells us that we can get a ~3% productivity increase if we double the size of our biggest cities. Double! The second one says that if we increase density by 2x, the number of jobs increases less than 2x.

Color me less than impressed. A stretch goal for upsizing our cities would be in the vicinity of 20% growth. That might—might—produce a 0.7% increase in productivity. That's not even measurable. And the price to pay is fewer jobs per worker.

Besides, what accounts for the increase of productivity in cities? The usual answer is tight linkages, sharing of information, ease of changing jobs, etc. But I'll put my money on something else. Here's a hint:

Worldwide, productivity is strongly correlated to education. Here's the United States:

Worldwide, productivity is strongly correlated to education. Here's the United States:

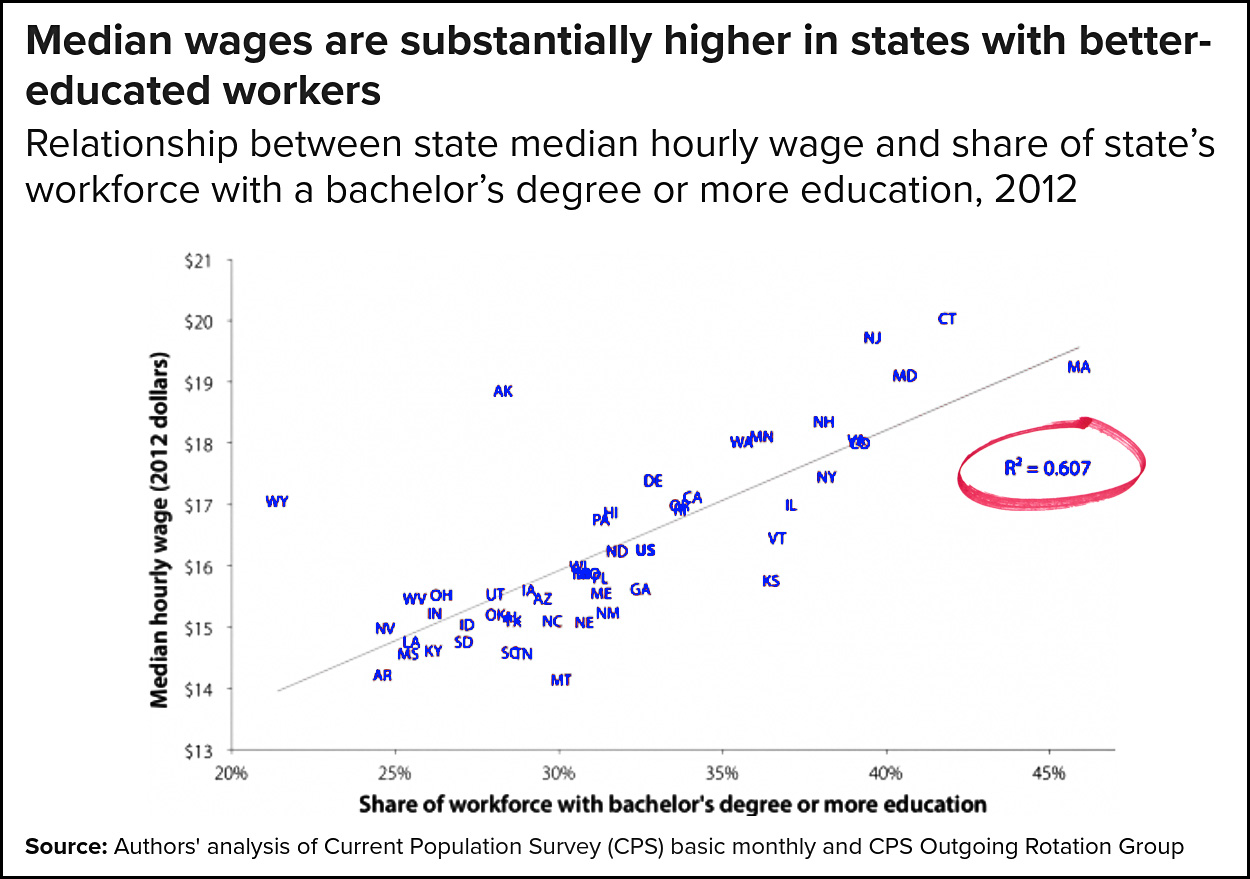

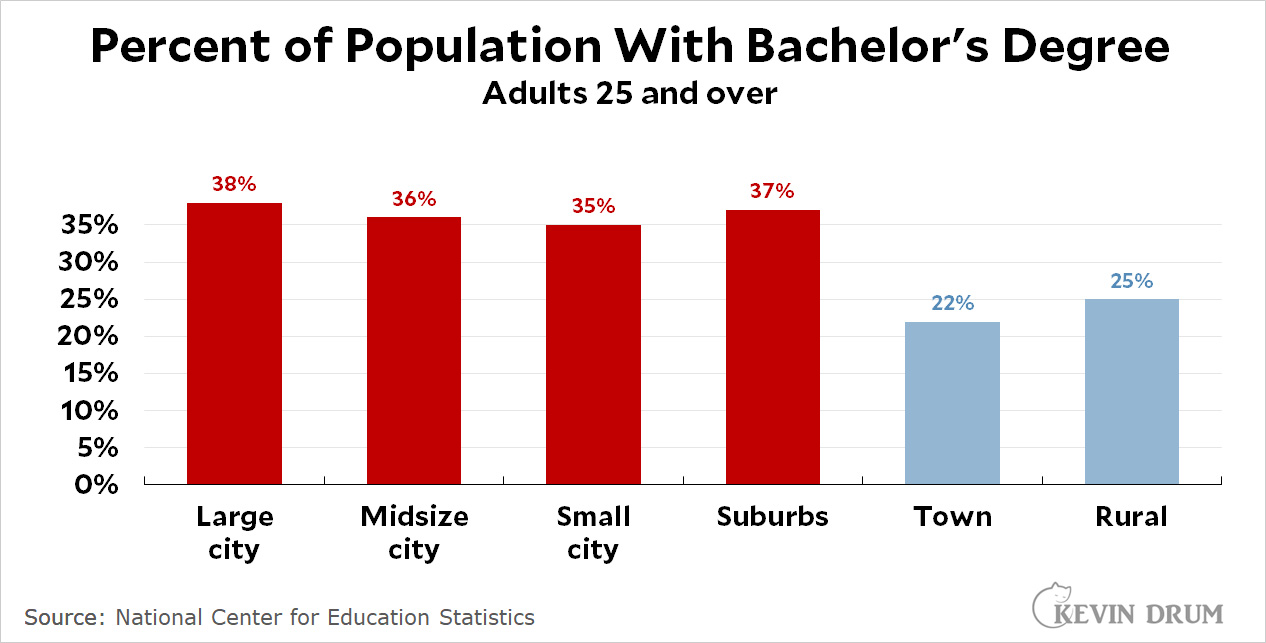

This chart comes from the lefties at EPI and it shows the same thing: productivity is very strongly linked to education. Now here's the education level in urban vs. rural areas:

This chart comes from the lefties at EPI and it shows the same thing: productivity is very strongly linked to education. Now here's the education level in urban vs. rural areas:

The big difference is not between big and small cities, or between cities and suburbs. They're all about the same. The difference is between urban and rural.

The big difference is not between big and small cities, or between cities and suburbs. They're all about the same. The difference is between urban and rural.

This is all just a scattering of data, not any kind of rigorous study. Still, the conclusion is pretty obvious and also pretty reasonable: the real productivity booster is education. Cities aren't more productive because they're denser, they're more productive because it's where college-educated folks live. Increasing the size of big cities is unlikely to increase productivity at all unless you make sure to attract an outsized number of people with college degrees. This, of course, would make our rural areas even worse off.

The more obvious solution, if you really care about productivity and economic growth, is to try to increase the educational level of towns and rural areas. That's no easy task, but then again, neither is fighting endless bloody battles with city residents over every half percentage point in increased density.

POSTSCRIPT: On another point, I do wish that people would stop saying that "the US" has a housing shortage of 4 million or 5 million or whatever. The right way to put it is that California has a housing shortage of 4 or 5 million and everyone else is in roughly decent shape.

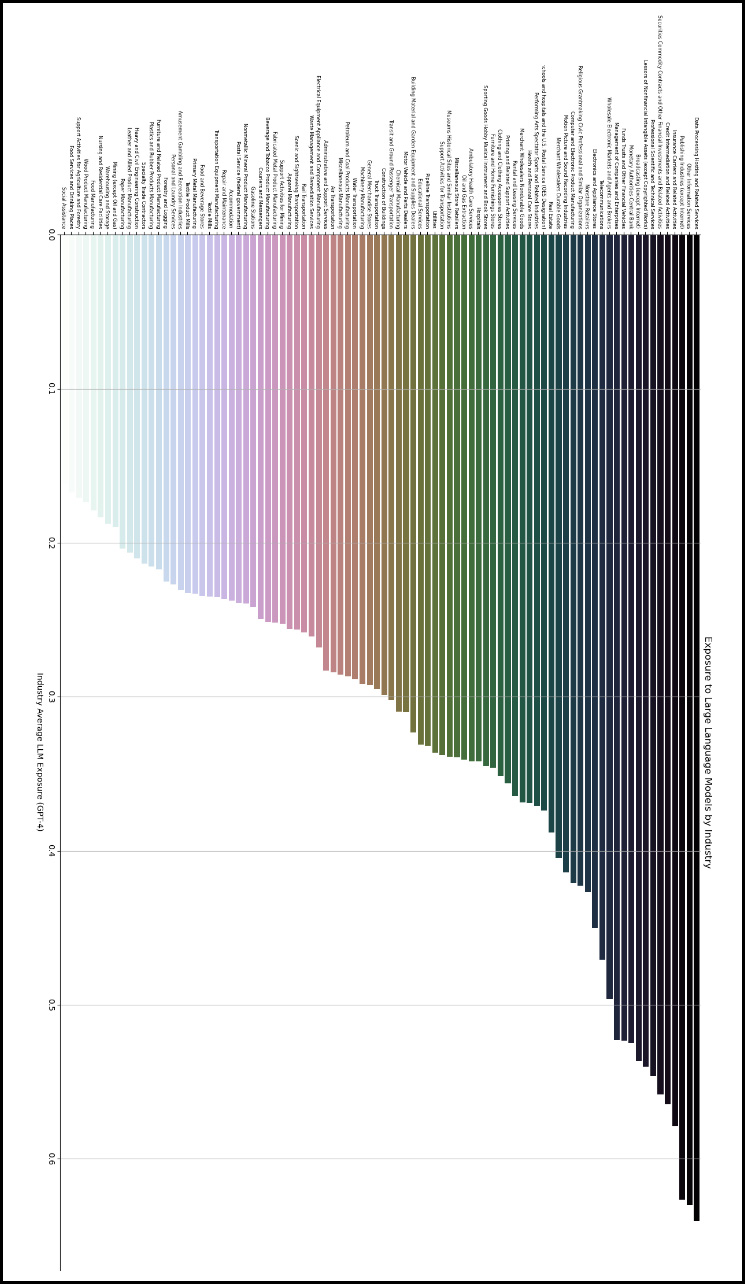

Here’s a list of jobs that are safe from the ChatGPT revolution

A new paper is out today that tries to estimate job losses from ChatGPT and other similar apps based on Large Language Models. The paper includes much talk of binning and rubrics and OLS regressions, all with lots of Greek letters scattered around. But you don't care about that, since it all boils down to "this is a rough guess."

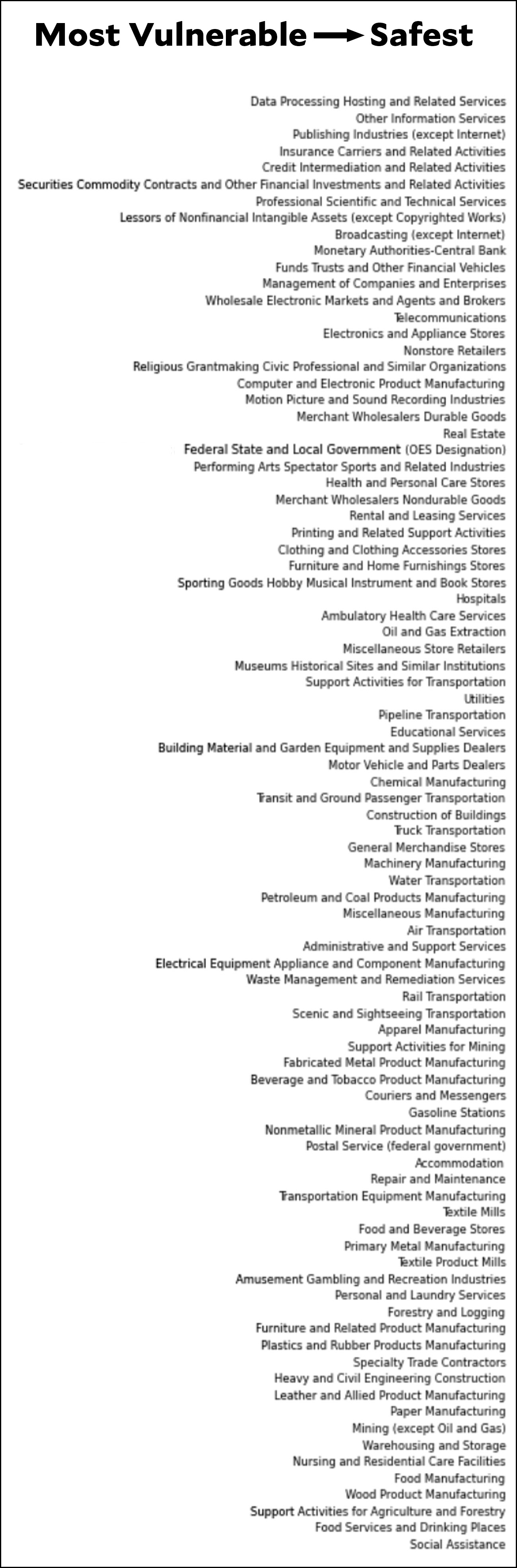

What you care about is the final result. Which jobs are safe and which are going to disappear thanks to GPT software? The authors present estimates from human experts and from a machine algorithm, and naturally we want to see what the machine says. Here it is:

Oops! You poor humans can't read that, can you? Fine. Here's a slightly more human readable version, with the most vulnerable jobs at the top:

Oops! You poor humans can't read that, can you? Fine. Here's a slightly more human readable version, with the most vulnerable jobs at the top:

Social workers finally get their due! They are apparently the workers who are safest from computer overlordship in our brave new GPT world. More generally, if your job requires you to work with either people or stuff, you're in decent shape. But if your job primarily requires you to shuffle words and numbers around on a computer, you may want to think about changing careers over the next decade or so.

Social workers finally get their due! They are apparently the workers who are safest from computer overlordship in our brave new GPT world. More generally, if your job requires you to work with either people or stuff, you're in decent shape. But if your job primarily requires you to shuffle words and numbers around on a computer, you may want to think about changing careers over the next decade or so.

First Republic was a strong bank, but not strong enough during a panic

The latest on First Republic Bank:

Eleven big banks banded together last week to deposit $30 billion in First Republic in an effort to restore confidence in the lender. The San Francisco-based bank’s customers have withdrawn some $70 billion since the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank earlier this month, The Wall Street Journal previously reported.

That's more than a third of FR's deposits. The fact that they faced a run like that and remained in business is prima facie evidence that they were in pretty strong shape to begin with.

(Note that this is not the same as Credit Suisse. FR is a strong bank that got hit by a panic. Conversely, Credit Suisse has been in trouble off and on for the past decade, and the panic over Silicon Valley Bank was just the straw that broke the camel's back. They haven't been a strong bank for quite a while.)

I don't know what's going on here. But I will mention that I've long thought the answer to stabilizing the US banking system is to get rid of our thousands of little regional and community banks and consolidate them into maybe half a dozen giant banks. If you walk down any high street in Britain, that's what you'll see: the same four or five banks in every town, which collectively account for something like three-quarters of all retail banking.¹ The same is true in Sydney, Stuttgart, Milan, and most other places.

There was a time when small banks provided services that remote money center banks couldn't or didn't. But those days are long gone, and small banks don't really serve much purpose any longer. We'd be better off merging them into big banks and then regulating every bank the same way.

¹Investment and commercial banking are a different story.