I'm not an economist with a sophisticated macro model or anything like that, but even before this week I thought that a recession was almost inevitable. Here are the basic reasons why:

- The economy has been propped up by COVID-19 spending for a while, which is a good thing. But the last stimulus bill passed 15 months ago and is now fading out.

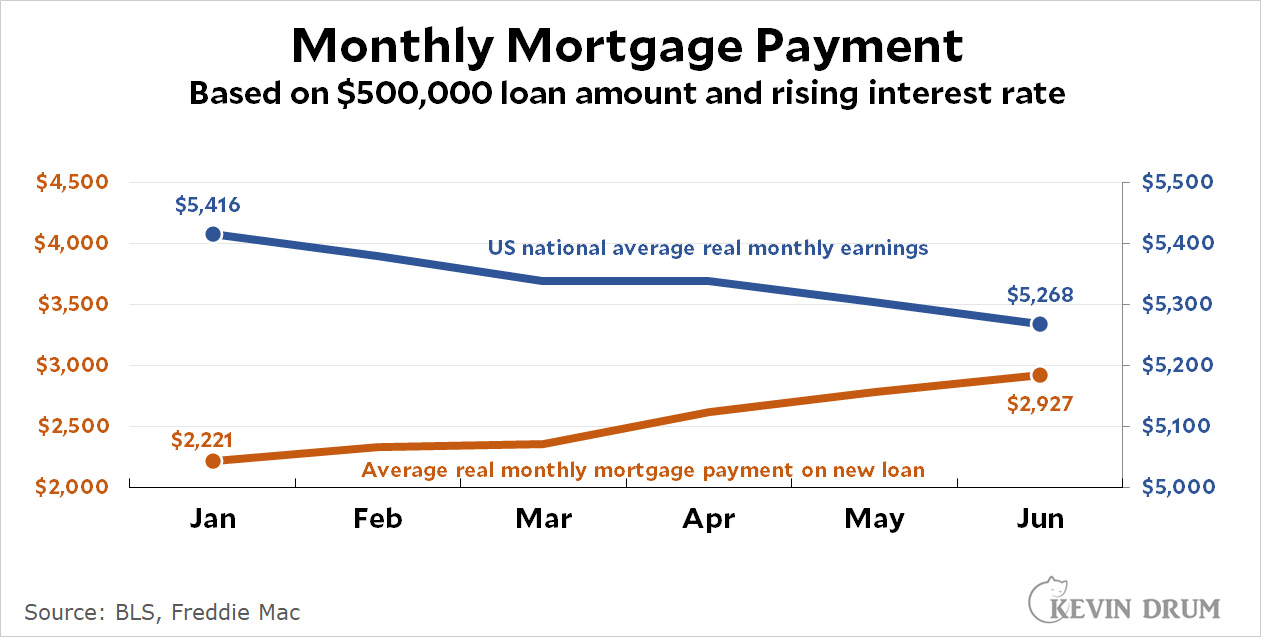

- Skyrocketing mortgage rates are going to squelch the housing market. This has a big effect on consumer spending (via the wealth effect) and on the residential construction industry—and it's happening at the same time that average earnings have been falling.

.

- Consumer spending has slowed down in 2022 and is now nearly flat.

- Companies that expanded recklessly during the pandemic are now finding that they have to cut back. Amazon is Exhibit A here.

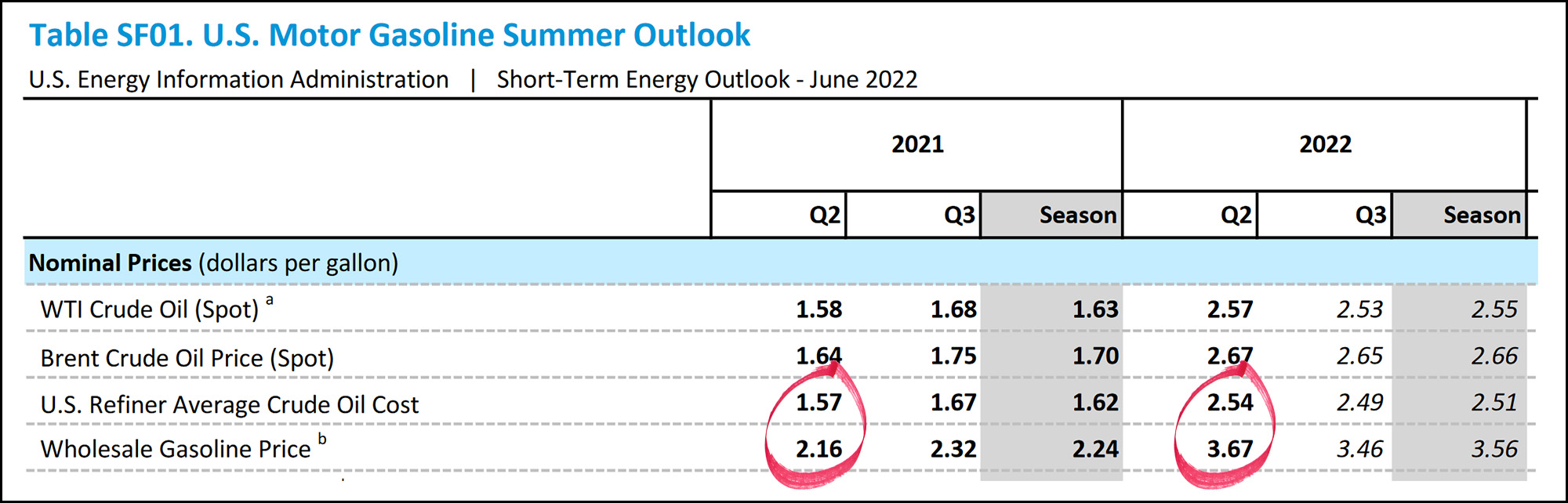

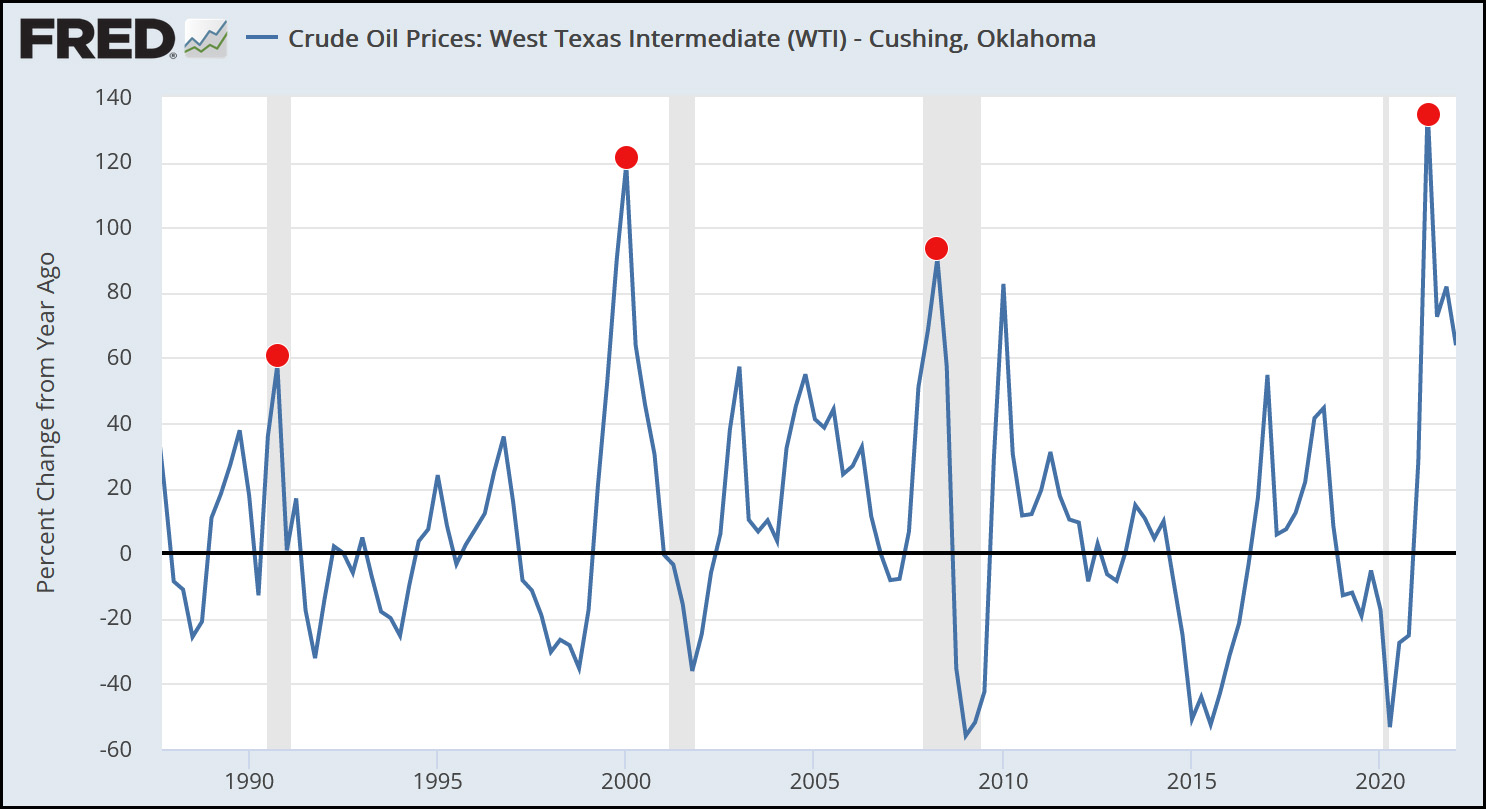

- In 2021 we had a huge spike in the price of oil. This is usually enough, all on its own, to produce a recession within a year or so.

.

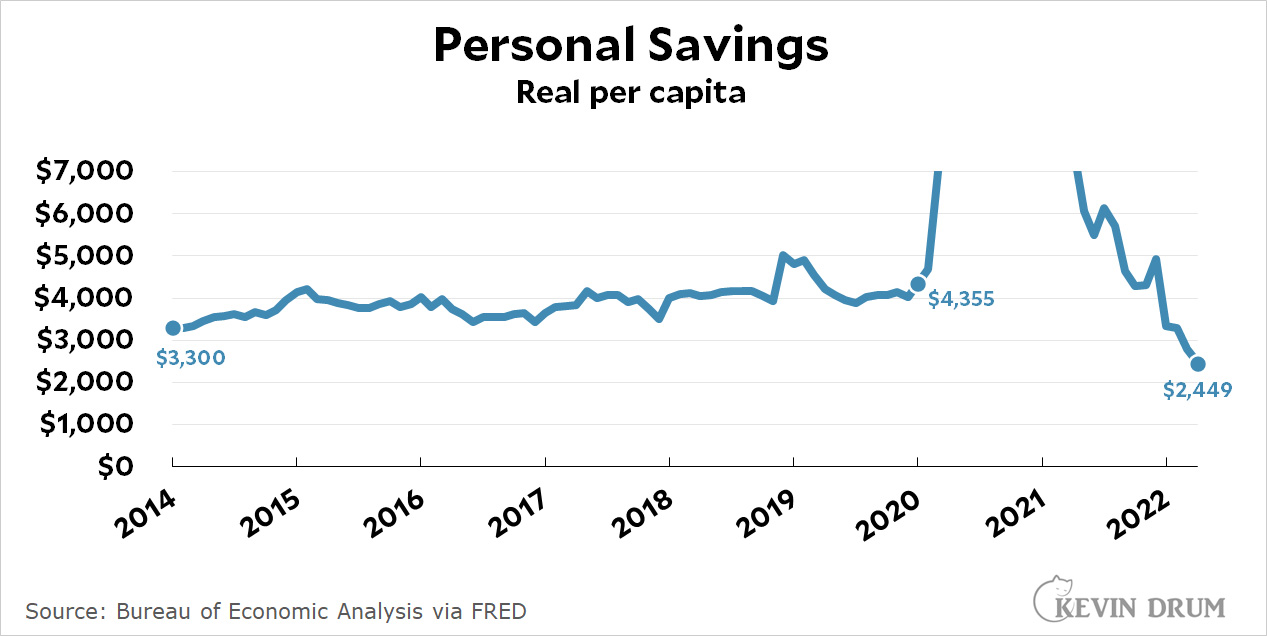

- Personal saving has dropped below its normal pre-pandemic level and consumer debt has risen above its normal level. Neither one offers any kind of buffer anymore.

.

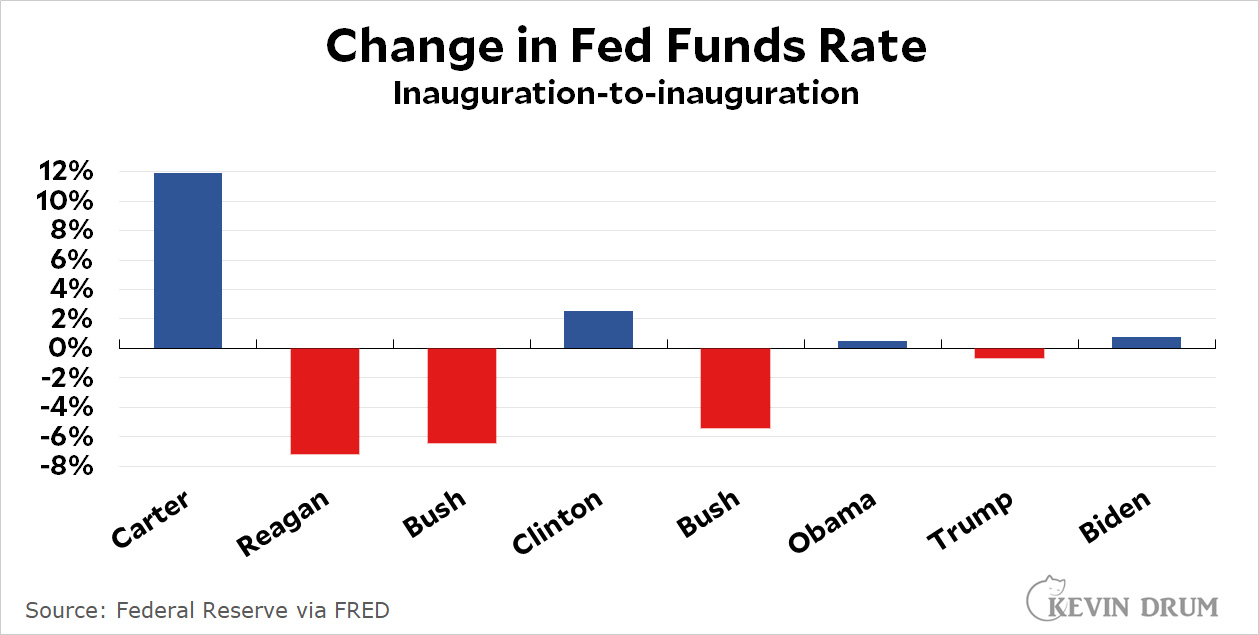

All this was enough to push us into a downturn already, but then the Fed decided on some "shock therapy" that will almost certainly be enough to finish the job. Both the stock and bond markets have delivered their verdicts on this, and it's hard to see what can stop an oncoming recession now.

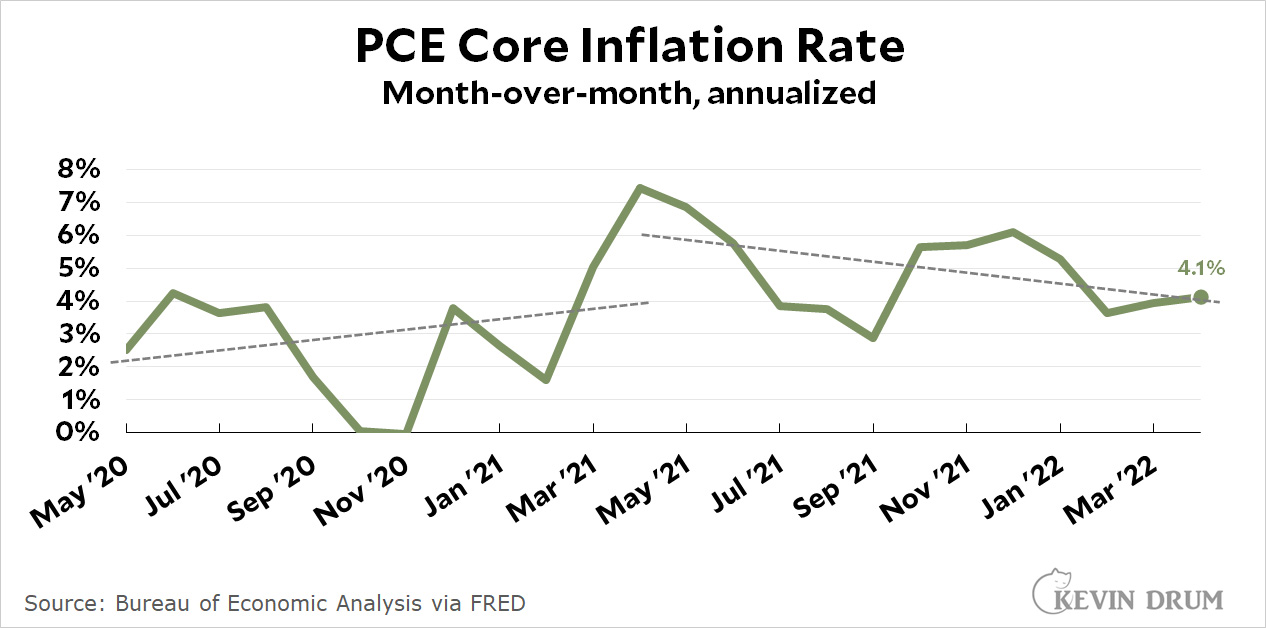

I'm not sure if I'm the last holdout on this or not, but I continue to think that inflation would have subsided on its own as the economy slowed, oil prices dropped back to normal, and supply chains eased. The Fed just needed to stay the course. Instead they panicked and decided a recession was the only way to attack high prices. And all because the May print of an inflation index they don't care about was 0.04% higher than March and therefore a "record."

The only good news here is that, to my eyes anyway, the economy is still in decent shape and we can probably count on a mild recession. Assuming, that is, that we don't panic even further.