Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through April 19. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Cats, charts, and politics

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through April 19. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

The police killing of Daunte Wright has sparked renewed interest in the use of routine traffic stops as a pretext for pulling over anyone that police deem "interesting," which mostly turns out to be Black men. That got me curious about how many routine stops turn into police killings of unarmed civilians. According to the Washington Post Fatal Fatal Force database, here's the answer for the year 2020:

The Post database is not the only source of this information, and I had to apply some judgment to distinguish "routine" traffic stops from others (mostly those where police were called to the scene). You can go through them yourself if you want, but I don't think anyone would disagree with my assessments by more than one or two at most.

There are two things to notice:

It's a little hard to know conclusions to draw here. On the one hand, the racial disparity is unbelievably huge. On the other hand, the absolute numbers are tiny. A grand total of four unarmed Black drivers were killed by police during routine traffic stops in the entire year 2020.

That said, these are the facts. It's up to you to decide what you think they mean.

The Washington Post reports that the business community is mostly OK with modest tax increases to fund infrastructure:

Corporate America’s relatively muted reaction thus far to significant tax hikes was until recently unthinkable and reflects major changes in U.S. politics — the most important of which may be the recent falling out between the GOP and business elites.

When congressional Republicans worked to approve a $2 trillion tax cut in 2017, the GOP and corporate America worked together seamlessly to build support for the measure and push it into law.

Now, that relationship is under unprecedented strain. Congressional Republicans are incensed by corporate criticisms over GOP-backed voting restrictions and stances on culture war issues. Business groups, meanwhile, have increasingly eyed the GOP as a dangerous partner, toxic to their brand and harmful to their ability to recruit young worker talent.

Hmmm. "Toxic" to their brand. Here is Yale associate dean Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, who is extremely plugged in to the CEO community, in a Politico story from a few days ago:

Divisiveness in society is not in their interest—short term or long term. They don’t want angry communities; they don’t want fractious, finger-pointing workforces; they don’t want hostile customers; they don’t want confused and angry shareholders.... That is 100 percent at variance with what the business community wants. And that is a million times more important to them than how many dollars of taxes are paid here or there.

If [corporate tax rates] go from 34 percent to 27 percent instead of 22 percent, they’re way less concerned about that. There’s too much focus on taxes. On taxes, what we’re seeing is, in fact, CEOs are willing to concede. There’s a lot of ground there.

The bottom line, so to speak, is that in the past the business community stayed in its lane and didn't worry much about the social conservative wing of the Republican Party. But now they feel like it's out of control and bad for business. Like it or not, big corporations have mostly adopted the vaguely liberal "responsible citizen" attitude of the majority of Americans, namely that climate change is bad; diversity is good; mass killings are bad; immigration is good; trade wars are bad; trans people are good; and so forth. This is the corporate persona that they actively promote in their advertising, and they do it because their market research says this is what most people want.

And of course, perhaps most important, boycotts are bad. Corporations want to sell their stuff to everyone and not have to worry about either side going medieval on them because they're forced to take public sides on issues they don't truly care that much about.

Now, this is an interesting perspective, and you can add to it the fact that businesses, more than individuals, are keenly aware that they need high-quality infrastructure to survive. So they're willing to pony up some new taxes because taxes are, to them, just a cost of doing business, not a holy war led by the ghost of Ronald Reagan.

This all makes sense but it is absolutely not a sign for Democrats to go hog wild in hopes that corporate America has abandoned the GOP for good. For one thing, businesses do still care about unions and regulations, and that's going to keep them at arms distance from Democrats. What's more, they haven't suddenly become a bunch of Bernie bros. All they want is for Republicans to turn down the volume a bit.

In the end, they believe that a happy, contented consumer base is a consumer base that spends lots of money. So that's what they want. Joe Biden may be a Democrat, but he seems very familiar to them in his guise of happy, contented Uncle Joe. By contrast, Tom Cotton and Josh Hawley and Tucker Carlson and others seem like they're doing nothing but upsetting the apple cart over trivial crap like Dr. Seuss and trans bathrooms that no one would care about if they'd just shut up about it.

The big question, of course, is whether they're willing to put their money where their mouths are and stop funding the party if it doesn't calm down. I have my doubts about that. After all, those Democrats and their regulations are still waiting in the wings.

It's Milky Way season again! I happened to be out in dark-sky country early Saturday morning and took this picture against the background of Interstate 15. It's not very good, though. I was a few miles south of Barstow, which means I was still too close to the hegemony of the Los Angeles light dome, as well as the smaller Barstow and Victorville light domes. Plus it was only a little more than an hour until sunrise, so the sky wasn't completely dark.

I'm certain to have better opportunities later in the summer. This is just the start.

The LA Times has an interesting piece this morning about the police killing of Adam Toledo in Chicago last week. There have been the usual protests about police conduct, but they've been muted because it turns out that not everyone in Toledo's neighborhood blames the cops:

A steady stream of mourners visited the memorial this weekend, some pausing to pray. Most were Latino, their roots Mexican, Puerto Rican and Central American. Many said the youth was a victim of police brutality. But some also observed that he was out in the early hours of the morning with a member of the gangs who terrorize them.

“I see both sides: It’s tragic for the officer and for the young man,” said Elsie Franqui, 45, who brought her 12-year-old son and 14-year-old nephew to the memorial Saturday with Viva Honduras masks (she’s Puerto Rican, her husband Honduran) and a homemade votive candle bearing Adam’s photo.

....Fernando Serrano, 48, who rode his bike from his nearby apartment to watch the protest, didn’t see police as the only problem....“A 13-year-old should not be on the street at 2:30 a.m. with a gun,” said Serrano, a Puerto Rican-born father of three who works at Home Depot, grew up in Logan Square and married a Mexican woman from Little Village. “It could happen again tonight. There are parents worse off.”

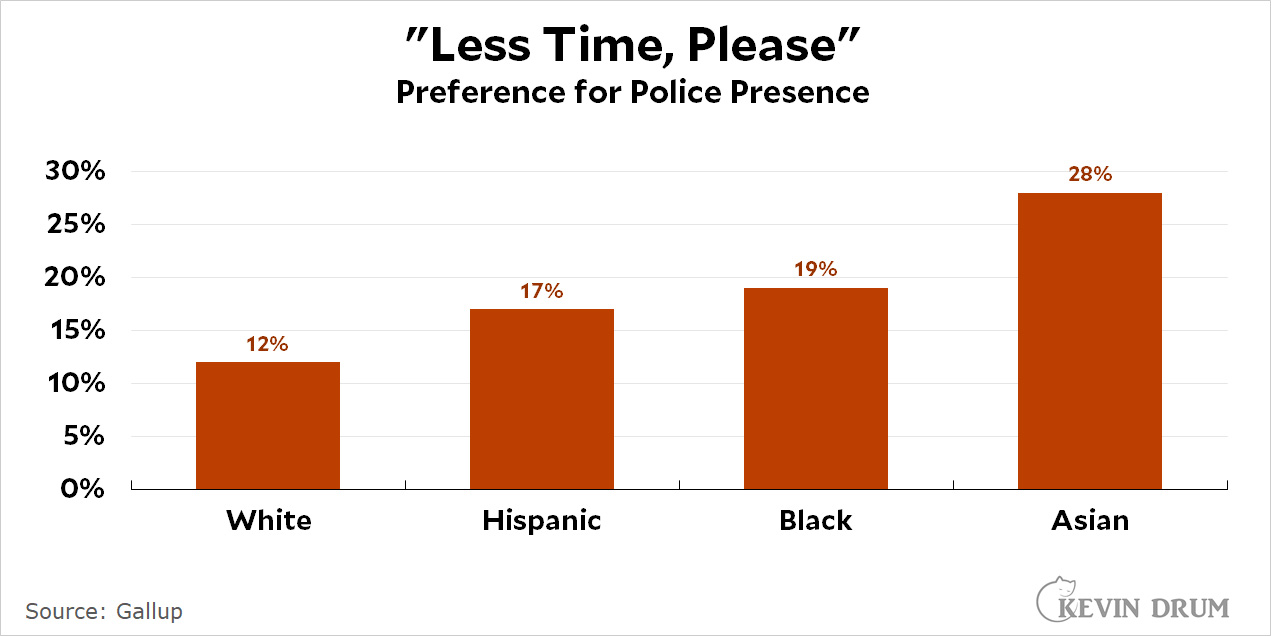

This appears to be something of a minority view, but it's clearly lurking under the surface. And it gibes with the fact that, despite everything, only a small minority of Black and Hispanic poll respondents say they favor a decrease in police presence in their communities:

I wonder how common this is? When reporters go out to hot spots, it's easy to find activists on the streets who are eager to provide anti-police quotes and demands for less police presence. But what about all the people who stay home and don't attend the rallies? They're a lot harder to track down, but they might provide a very different viewpoint. This is something reporters ought to think about when they're on the scene and have the time to canvass a few homes for alternate views.

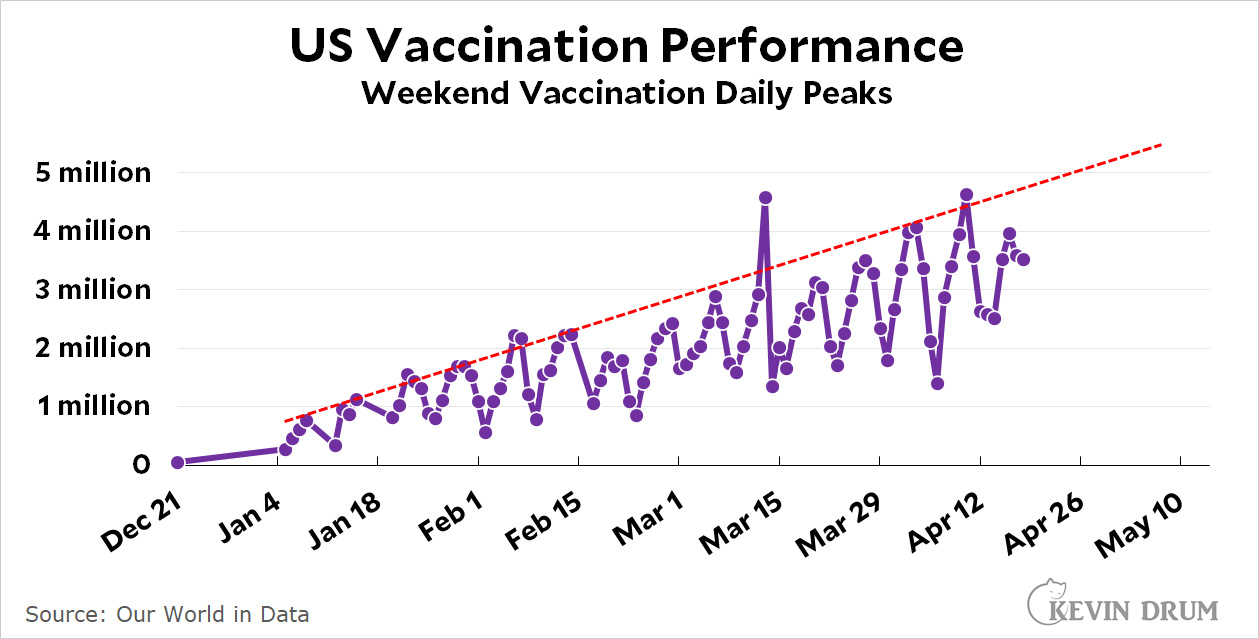

We delivered more than 4 million doses of vaccine on Friday, and it's a measure of how well we're doing that this seems a little disappointing. Shouldn't we be up to 5 million by now? 6 million? Come on!

Anyway, here are the numbers at this point: 33% of the adult population has been fully vaccinated; 50% have received at least one dose; and we have administered 80 doses of the vaccine per 100 adults.

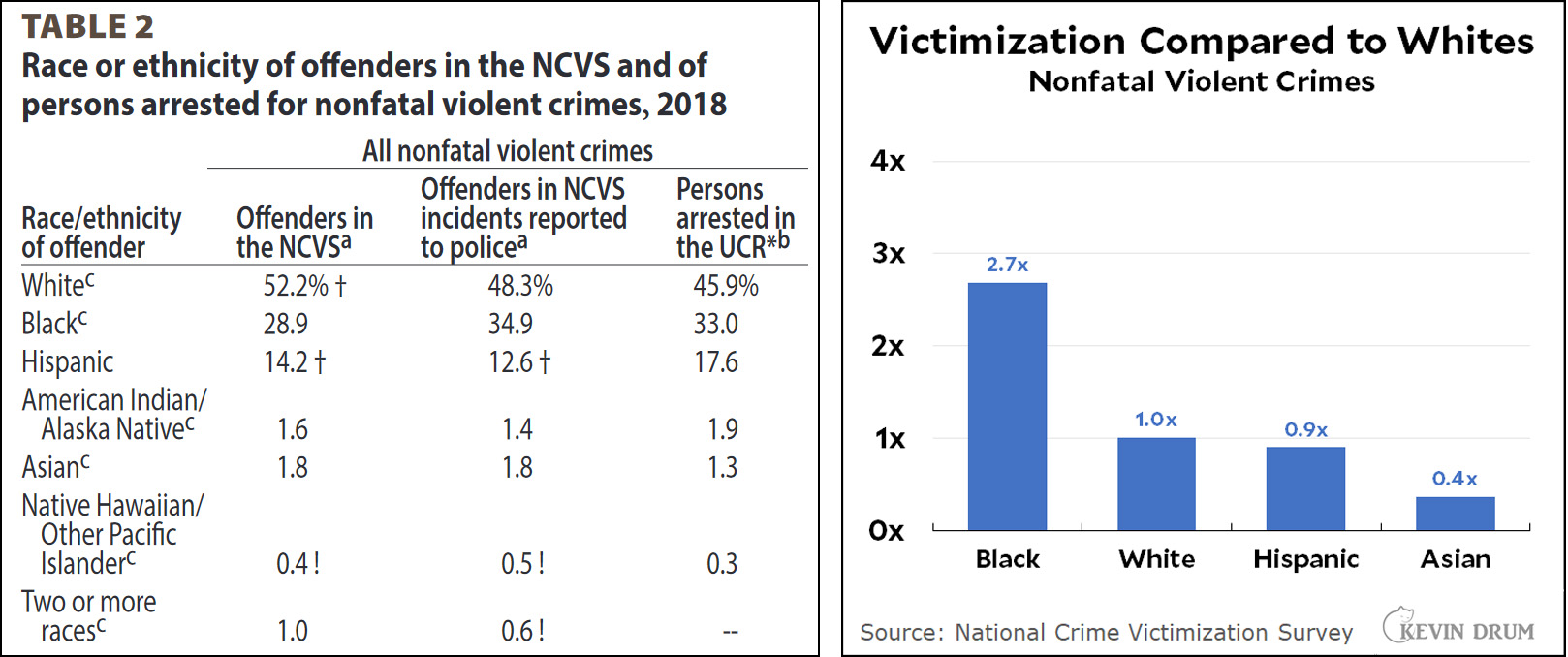

What is the underlying rate of Black crime vs. white crime? This is a tricky question to answer, but recently the Bureau of Justice Statistics took a crack at it in "Race and Ethnicity of Violent Crime Offenders and Arrestees, 2018." Their basic results boil down to two tables, the first of which is derived from the FBI's Uniform Crime Reporting. It's below on the left:

Table 1 shows that Black people account for 33% of arrests for nonfatal violent crimes compared to a 12.5% share of the population. A little arithmetic produces the chart on the right, which shows that Black people are arrested at about 3.5x the rate of white people.

The problem with arrest rates is that they might not represent the underlying crime rate. Instead, it's possible that Black and white crime rates are similar but racist policing policies produce more arrests of Black people.

But there's another way of looking at this. The National Crime Victimization Survey also estimates crime rates, but police aren't involved. It's a simple survey that asks people if they've been the target of a crime during the past year.

Now, there are obvious limitations to the NCVS. For starters, you can't call up people to ask if they've been murdered, so there are no homicide numbers. You also can't ask about race for most property crimes, since the victim of, say, a home burglary never sees the thief. That leaves violent crime other than murder, which is why the measure used here is "nonfatal violent crime."

That said, it's still a pretty useful measure. It's below on the left:

Again, a bit of arithmetic shows that survey respondents report being victimized by Black people at 2.7x the rate of white people. This is close to the arrest rate reported by the FBI even though it uses an entirely different methodology. That suggests the true underlying violent crime rate for Black people is in the ballpark of 3x that of white people.

However, at every step of the way the criminal justice system makes this worse. A careful study done in 2017 concludes that the lifetime Black felony conviction rate is 3.9x higher than the white rate. And a report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics says that Black people are currently imprisoned at a rate 4.2x higher than white people.

These are not all precisely comparable numbers. The 2017 study only goes through 2010 and includes all offenses, not just violent crime. The BJS report is for 2018, but it also includes all crimes. Nevertheless, these are relatively minor differences. Here's how the whole thing looks, with each number representing the Black rate as a multiple of the white rate:

It's wise not to put too much faith in the precise value of each of these numbers, but the trend is obvious. By the time the ratchet is finished, the Black community is in prison at a proportion that's half again larger than their underlying crime rate.

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through April 18. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through April 17. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Over at NRO, Jason Richwine says that the public health establishment has lost credibility. As it happens, I agree that the CDC and other public health experts have been too conservative in their advice, seemingly unwilling to state the facts clearly and simply for fear that the public will misinterpret them and go hog wild. At the same time, I can also understand their fear. Americans have not demonstrated a ton of self discipline in response to the pandemic.

But that's a general criticism. Richwine offers up four specific instances where he says the public health establishment blew it big time. But I don't think any of them hold water. Here they are:

Reversal on masking. This is the one people bring up constantly, but it's hardly some kind of unique CDC failing. Every European country reacted just like we did, and they reversed themselves for the same reason: because the science changed. At the start of the pandemic, epidemiologists simply weren't sure how the coronavirus spread or whether it could spread at all from asymptomatic individuals. Given this, it seemed as though masks were of little use to the general public unless they were already sick with COVID-19, so they recommended saving masks for healthcare professionals. There was really nothing wrong with this response, just as there was nothing wrong with reversing when the science evolved and it became clear that asymptomatic individuals could spread the virus.

Lockdowns. I don't quite get this one, but Richwine is annoyed that "the justification for lockdowns changed from avoiding overrun hospitals to minimizing transmission generally." I'm not quite sure what was wrong with adding new justifications as the science changed and the pandemic became far more serious, but Richwine says it caused "an endless hodgepodge of restrictions" that confused a lot of people. That's true, for two reasons. First, the science was evolving and there simply weren't firm answers about what practices were most effective. That's just the way things go when you encounter a brand new virus. Second, lockdowns are the purview of states and localities, and they were legally free to do whatever they wanted. There's nothing anyone could do about that, and in any case it doesn't reflect one way or the other on the public health establishment.

BLM protests. In early June a group of epidemiologists at the University of Washington wrote an open letter defending BLM protests on the grounds that racism was as big a threat to Black health as COVID-19. Therefore, protesting racism was important even if the protests might produce a small uptick in COVID-19 cases.

To be honest, I suspect this is a letter that was probably best left unwritten. At the same time, it was circulated on Twitter and the vast majority of the signers are students, activists, non-specialist doctors, and so forth. What's more, it got 1,200 signatures, which is a tiny number for an internet letter like this. It simply doesn't reflect anything in particular about the "public health establishment."

Schools. Richwine chides the CDC for recommending closure of schools even after "reasonable evidence" showed it was safe to open them. I'm sympathetic to this, since I mostly agree that this is what the evidence pointed to. At the same time, I followed this fairly closely and the science was far from settled. This is a legit criticism, I think, but given the state of our knowledge and the CDC's desire to provide conservative advice,¹ it's not a slam-dunk mistake.

I'm not in the profession of defending the CDC at all costs, and they certainly made some terrible mistakes—the testing debacle being the most obvious. But whenever I look into this stuff, I come away thinking they didn't do as badly as many people seem to think. Sometimes it's because the critics are assuming that any advice which got a lot of media attention was CDC advice, even when it wasn't. Other times it simply seems to reflect a personal ax to grind because the CDC declined to agree with their own personal read of the evidence. Or, I suppose, sometimes it's just part of a general dislike for the CDC that predates the pandemic.

In any case, the CDC's record isn't spotless by any means. But I think it's a lot better than people give it credit for, especially when it was forced to work under the idiot demands of Donald Trump and his acolytes.

¹This, of course, is a general criticism of the CDC, and one we can all reasonably disagree about. How conservative should the CDC be in the advice it gives? That's not an easy question to answer.