What's with the worker shortage? Ben Casselman takes a crack at explaining:

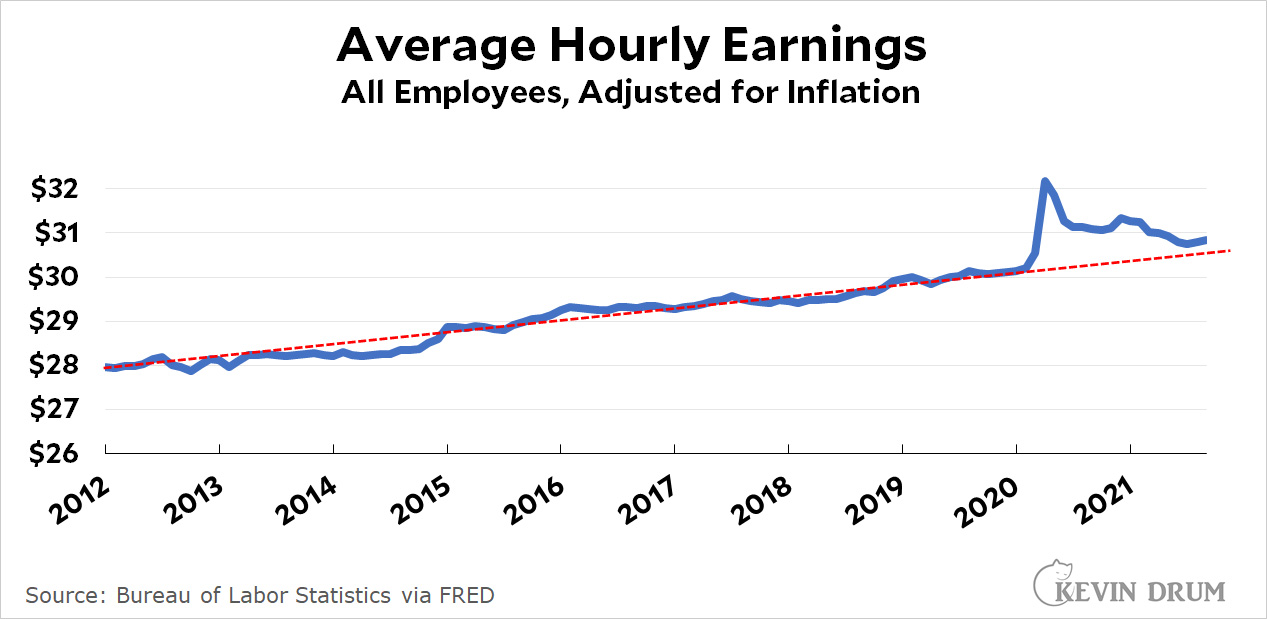

Conservatives have blamed generous unemployment benefits for keeping people at home, but evidence from states that ended the payments early suggests that any impact was small. Progressives say companies could find workers if they paid more, but the shortages aren’t limited to low-wage industries.

This is true, and it's very peculiar. It's one thing for McDonalds or Target to have trouble finding workers, but even unionized workplaces with pretty good pay and benefits seem to be having trouble. Onward:

Instead, economists point to a complex, overlapping web of factors, many of which could be slow to reverse.

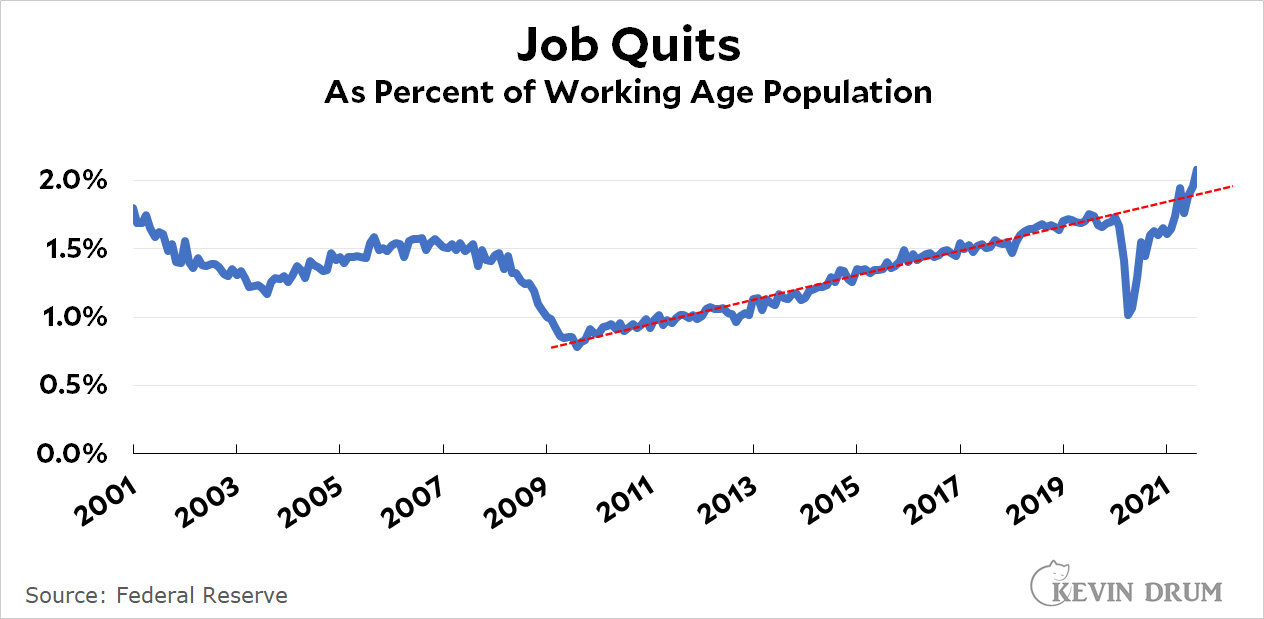

The health crisis is still making it hard or dangerous for some people to work, while savings built up during the pandemic have made it easier for others to turn down jobs they do not want. Psychology may also play a role: Surveys suggest that the pandemic led many to rethink their priorities, while the glut of open jobs — more than 10 million in August — may be motivating some to hold out for a better offer. The net result is that, arguably for the first time in decades, workers up and down the income ladder have leverage.

I guess. But two-thirds of the country is now vaccinated, and it's higher in some states than others. But do states with high vaccination rates have less of a worker shortage? I've seen no data to suggest that.

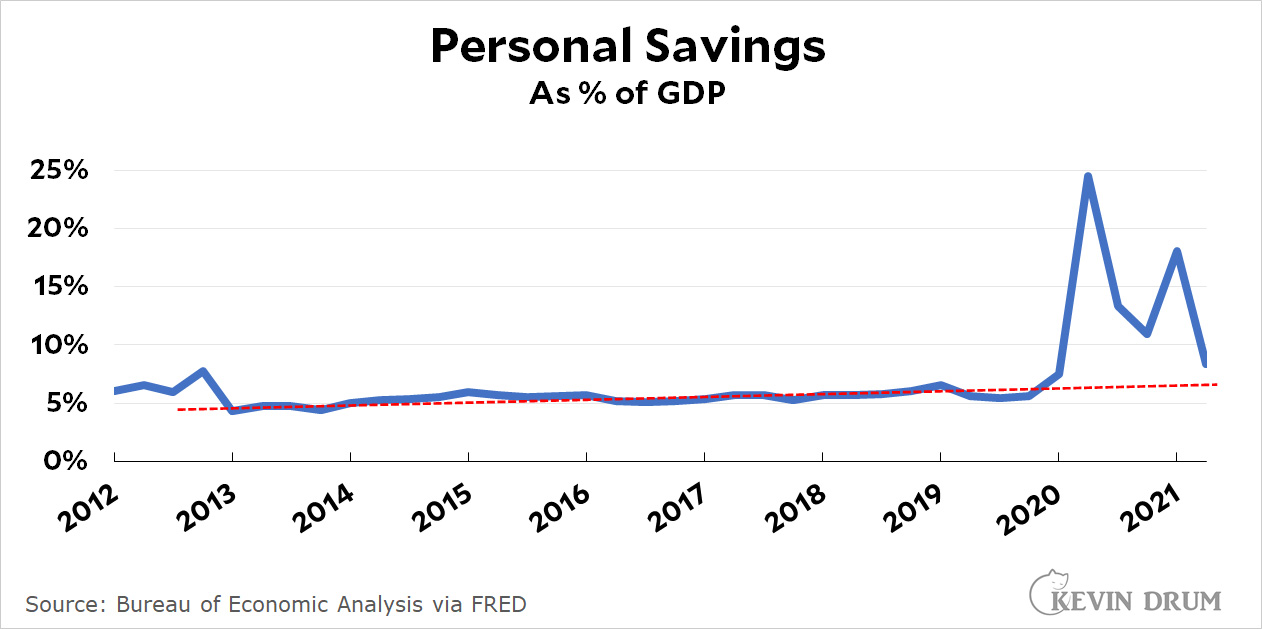

As for savings, that's a pretty reasonable suggestion. However, personal savings have largely been used up by now and there's still a worker shortage.

Finally there's all these people who are "rethinking their priorities." I hope Casselman will forgive me for thinking that this is a very upper-class New Yorkian suggestion. The vast, vast majority of ordinary middle-class workers are almost certainly not rethinking anything except the need to put food on the table.

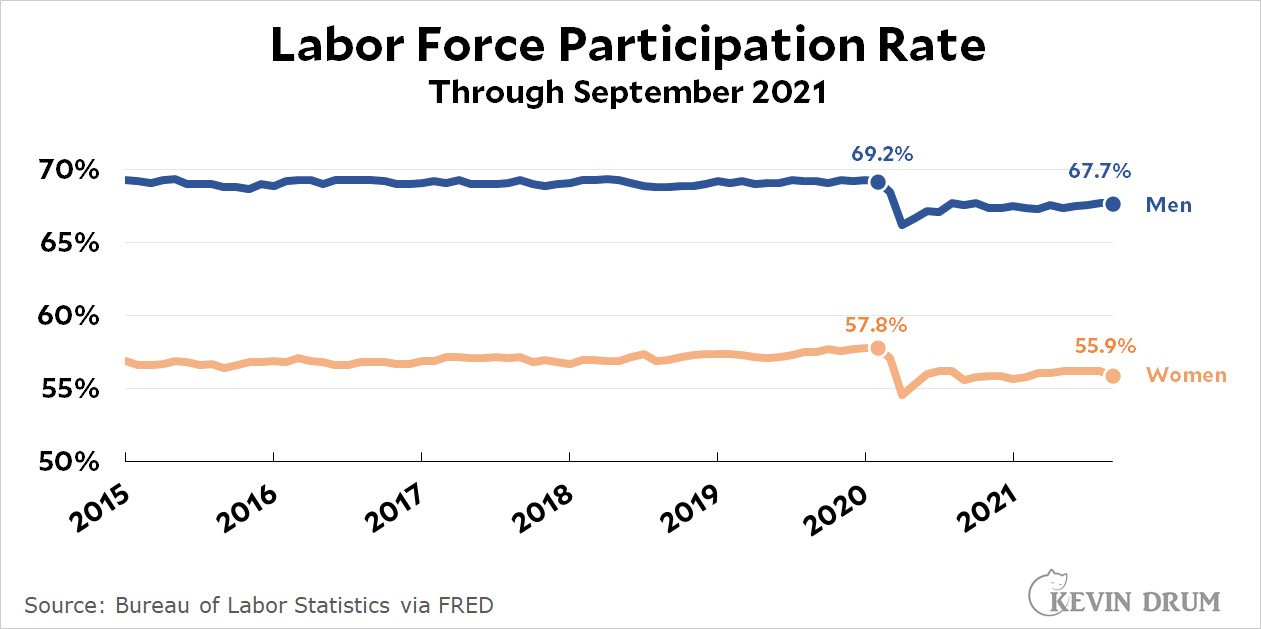

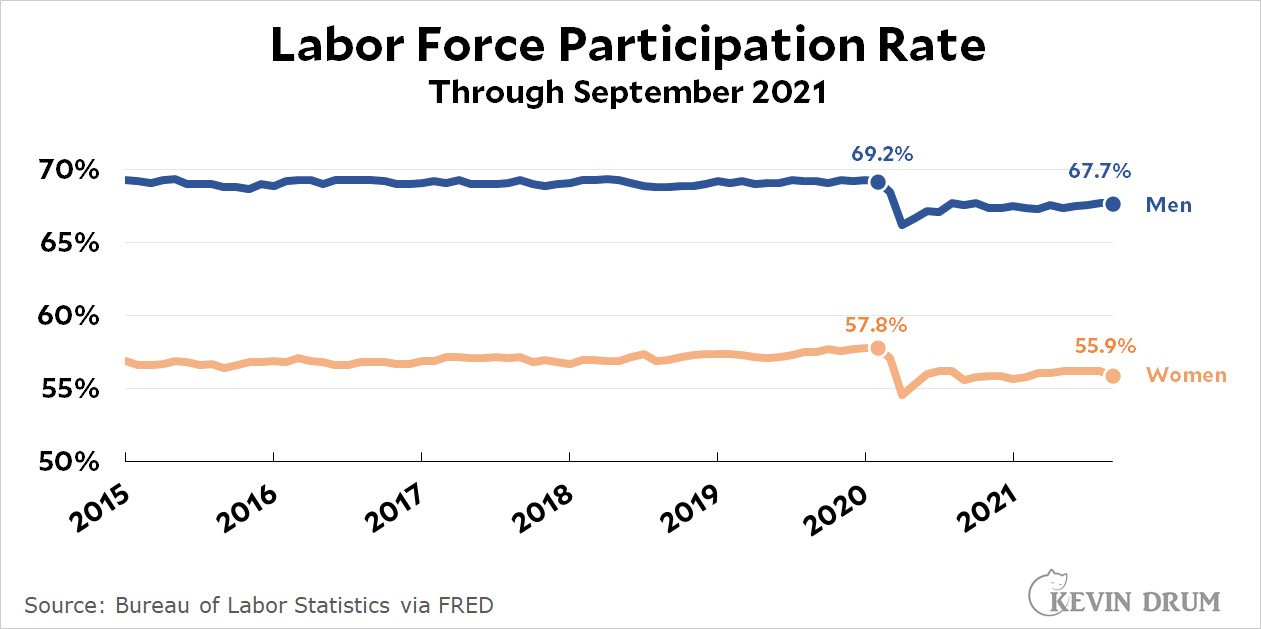

One subcategory of "thinking their priorities," however, could plausibly be women who have decided to stay home and care for their children rather than return to the paid workforce. But that doesn't really pan out either:

Women have dropped out of the workforce at a slightly higher rate than men, but even that small difference is only due to a blip in September. In August the numbers were nearly identical.

Women have dropped out of the workforce at a slightly higher rate than men, but even that small difference is only due to a blip in September. In August the numbers were nearly identical.

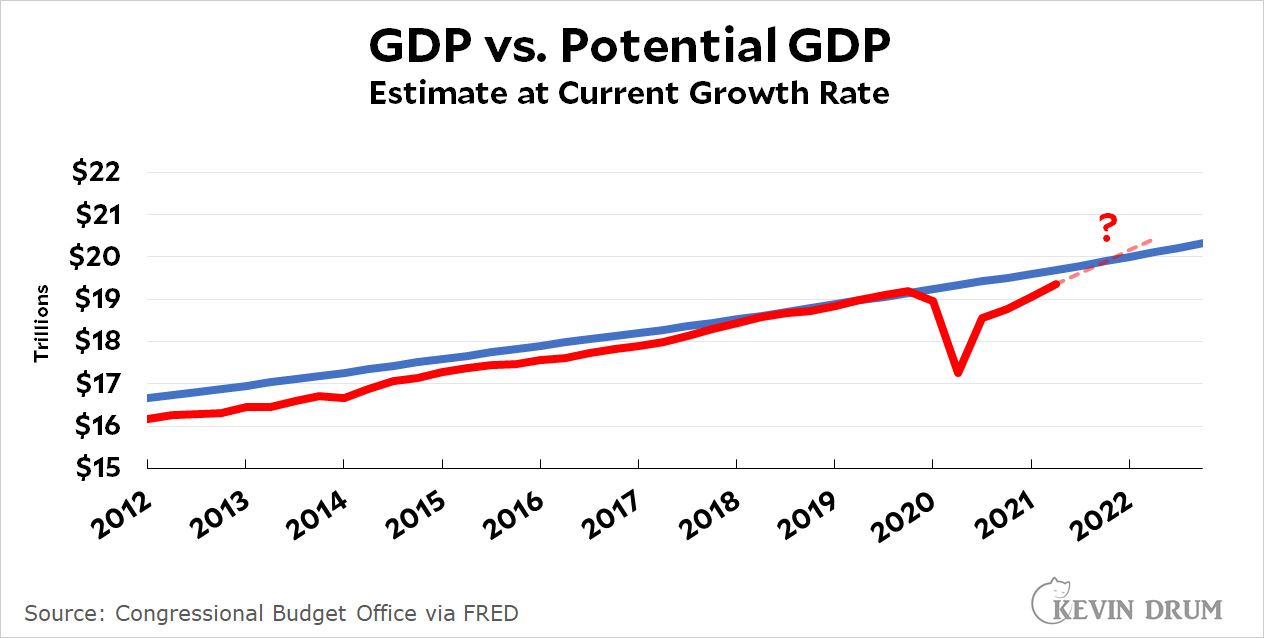

So we still have a mystery. But it just might be one with a silver lining. If workers were piling back into the workforce, it's possible that the economy really would be overheating, with dire consequences in the year ahead. Conversely, if they return slowly, the economy might continue on a strong but sustainable growth path. Just possibly, this might be a good mystery, not a bad one.