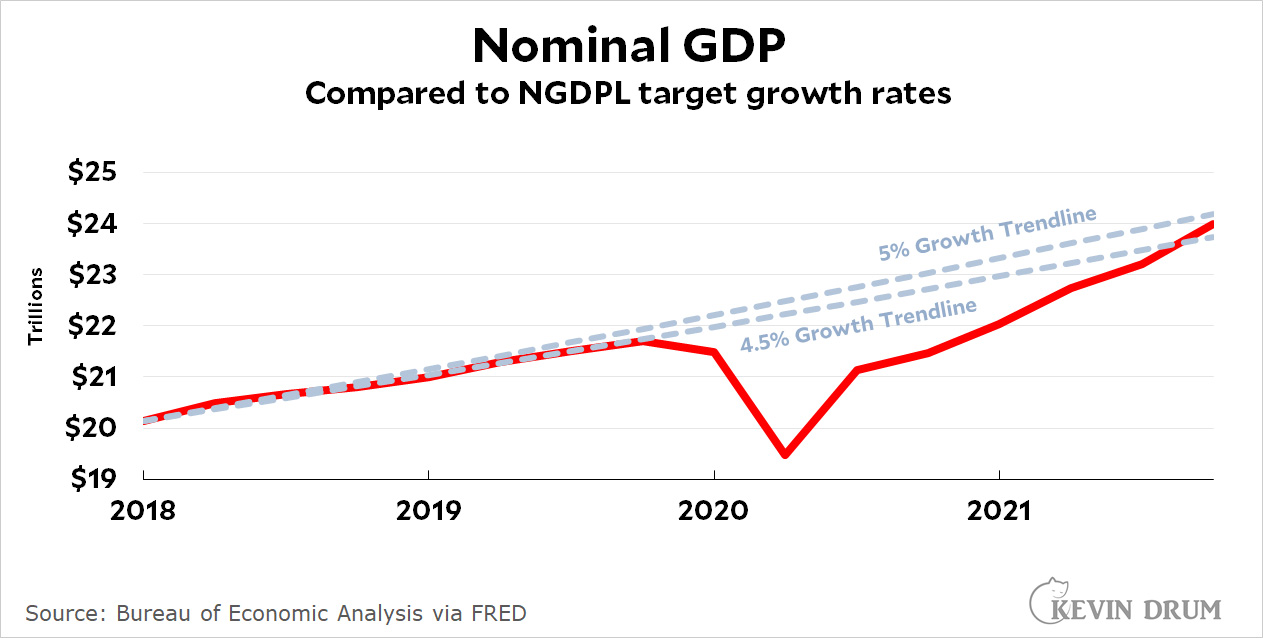

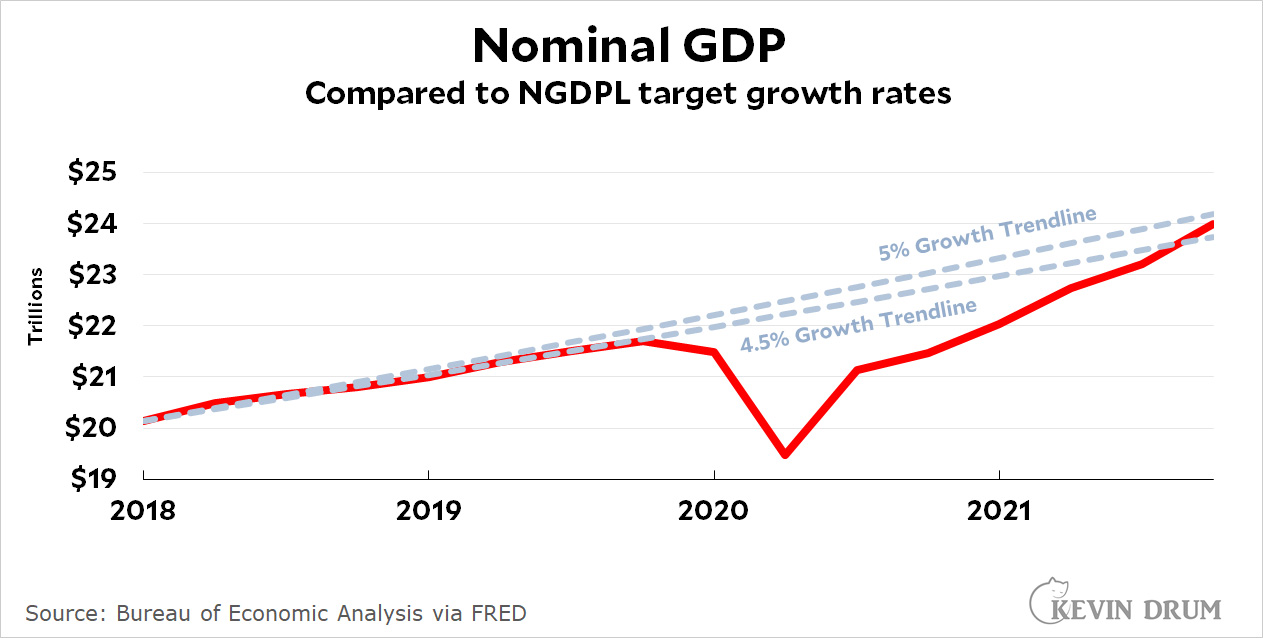

I've become a little obsessed with our inflation crisis, and yesterday evening I ran into a tweet about our old friend NGDP. This is nominal GDP—i.e., not adjusted for inflation—and there's a small cadre of economists who believe that this, not interest rates, is what the Fed should target. A common proposal is to target 5% growth annually in the NGDP level, which might consist of 2% inflation and 3% actual economic growth.

Or it might be 3% inflation and 2% economic growth. Or 5% and 0%. As long you hit the overall target, the economy will remain stable. When economic growth is low, the Fed will be forced to target higher inflation in order to bring the economy back to life. Likewise, when economic growth gets too hot and inflation goes up, the Fed will be forced to target lower growth in order to maintain its 5% overall target, and this will get inflation down.

But what if the Fed fails to hit the target? No problem. Since they're targeting the level of NGDP, it means they should make up for past years that failed to hit the target. If, say, 2021 ended with 4% growth, then the target for 2022 should be 6% in order to get the NGDP level up to where it should be.

Advocates argue that NGDPL targeting is better than current Fed policies because it works to stabilize not just demand shocks, but also asset bubbles and supply shocks. However, I've always been skeptical of the whole NGDPL argument, partly because it's not clear to me what mechanism the Fed would use to maintain its target levels. I also wonder why more smart economists haven't bought into it. Still, I thought it might be interesting to see how we're doing in a hypothetical NGDPL regime. Here it is:

As you can see, in the two years before the pandemic NGDP was growing pretty steadily at 4.5% per year. If you extend that trendline, we are now just slightly above it.

As you can see, in the two years before the pandemic NGDP was growing pretty steadily at 4.5% per year. If you extend that trendline, we are now just slightly above it.

On the other hand, if you look at a 5% growth trendline, then the NGDP level is still slightly under where it should be.

In either case, you can't really say that the economy is running especially hot by NGDPL standards. We're more or less where we're supposed to be. The only caveat is that in the final quarter of 2021 NGDP grew at an annualized rate of 14%. If that keeps up, we would quickly shoot far beyond our ideal NGDP level.

That said, it looks like the Fed—whether deliberately or not—has followed an NGDPL regime pretty well. By NGDP standards, we're right where we should be.

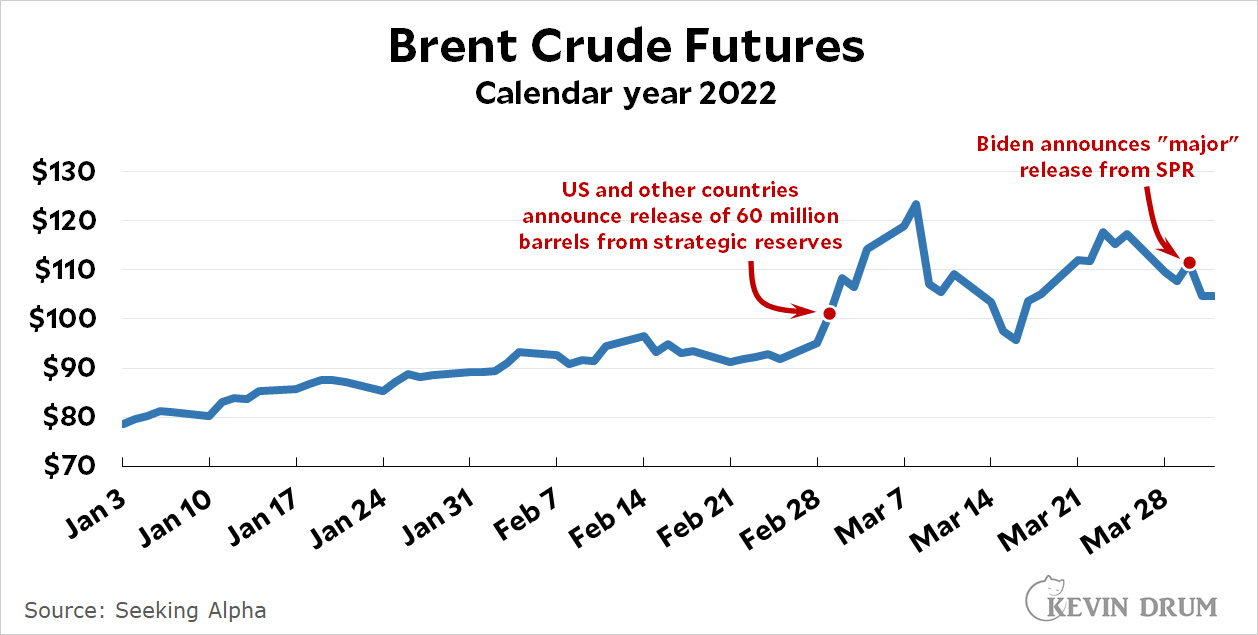

Everyone seems to have forgotten that President Biden first opened the SPR on March 1 after he and other leaders agreed to release 60 million barrels of crude from their national reserves. The US share of that was 30 million barrels.

Everyone seems to have forgotten that President Biden first opened the SPR on March 1 after he and other leaders agreed to release 60 million barrels of crude from their national reserves. The US share of that was 30 million barrels.