This is a surprisingly tricky question, but with a twist at the end. When you talk about earnings you have to account for at least three different things:

- Mean or median? Mean (aka "average" or "per capita") income is usually not a great measure because the ultra-wealthy skew it. If you have ten people making $50,000 and one person making $1 million, the mean income is a very misleading $136,000. Median is better: it records the halfway point of income and isn't heavily skewed by high incomes.

- Personal, family, or household? Personal is a single individual. A family is a group related by birth and marriage. A household includes everyone who lives in a particular housing unit.

- What income? There are lots of kinds of income. Cash income vs. benefits (like employer health care). Wages vs. investment income. Taxes (negative income) vs. government transfer payments. And capital gains are usually an entirely separate category.

Needless to say, there's also the distinction between nominal income and real income. Real income is adjusted for inflation and it's almost always what you should use. All of the charts in this post show real income.

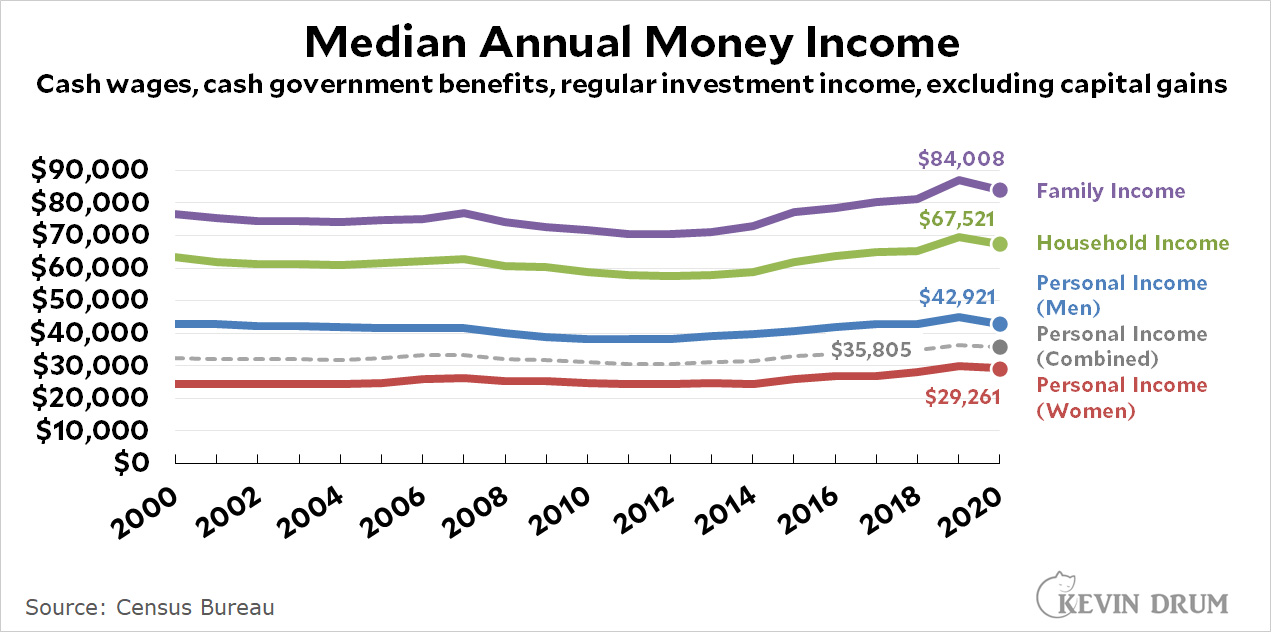

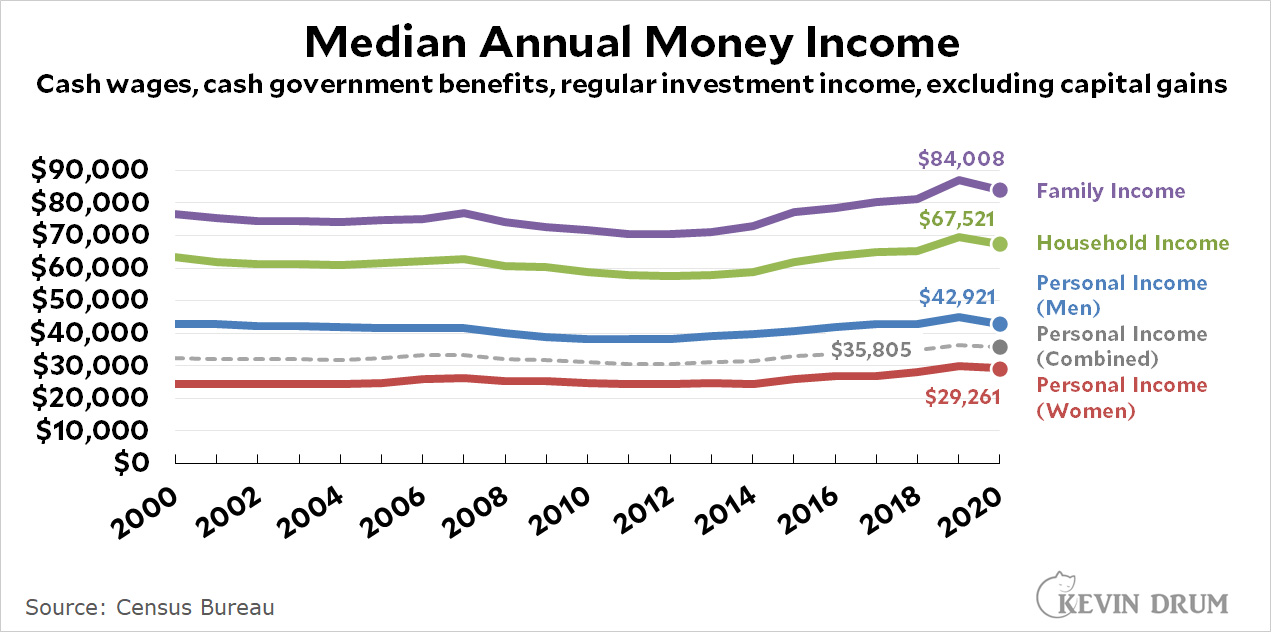

First off, the most commonly used set of earnings figures come from the Census Bureau:

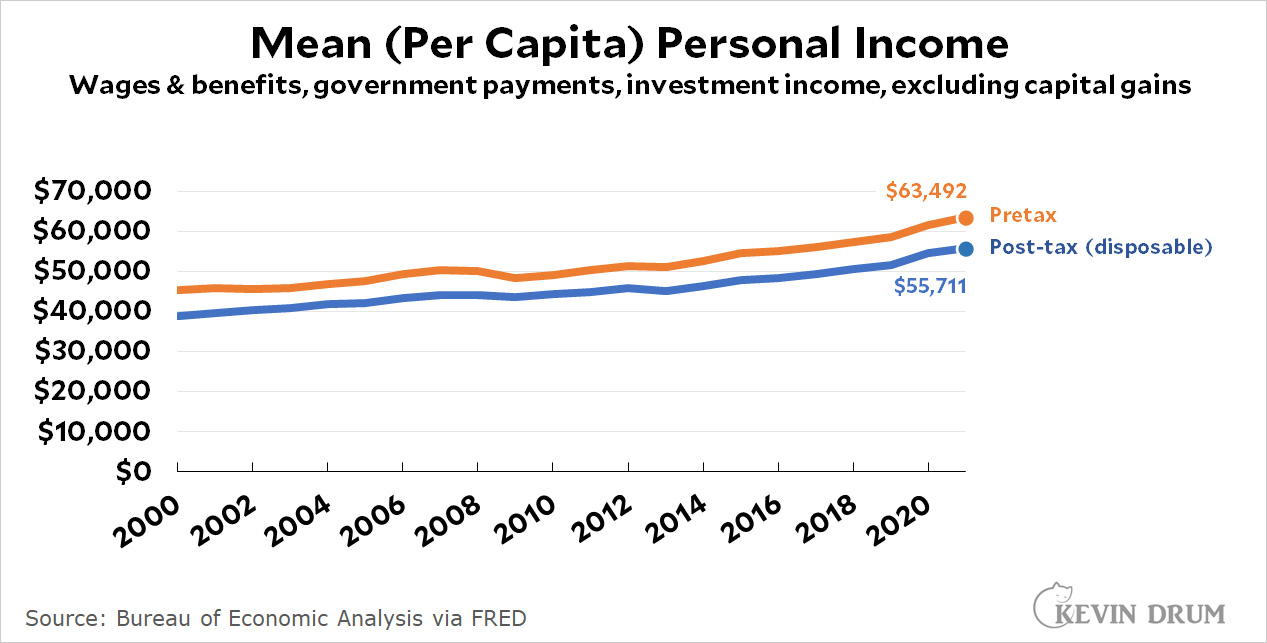

These figures are basically fine and are widely cited. They're really all you need for most purposes and they contain a wealth of breakdowns (gender, race, education, etc.). But if you want more, here's the personal income series from the Bureau of Economic Analysis:

These figures are basically fine and are widely cited. They're really all you need for most purposes and they contain a wealth of breakdowns (gender, race, education, etc.). But if you want more, here's the personal income series from the Bureau of Economic Analysis:

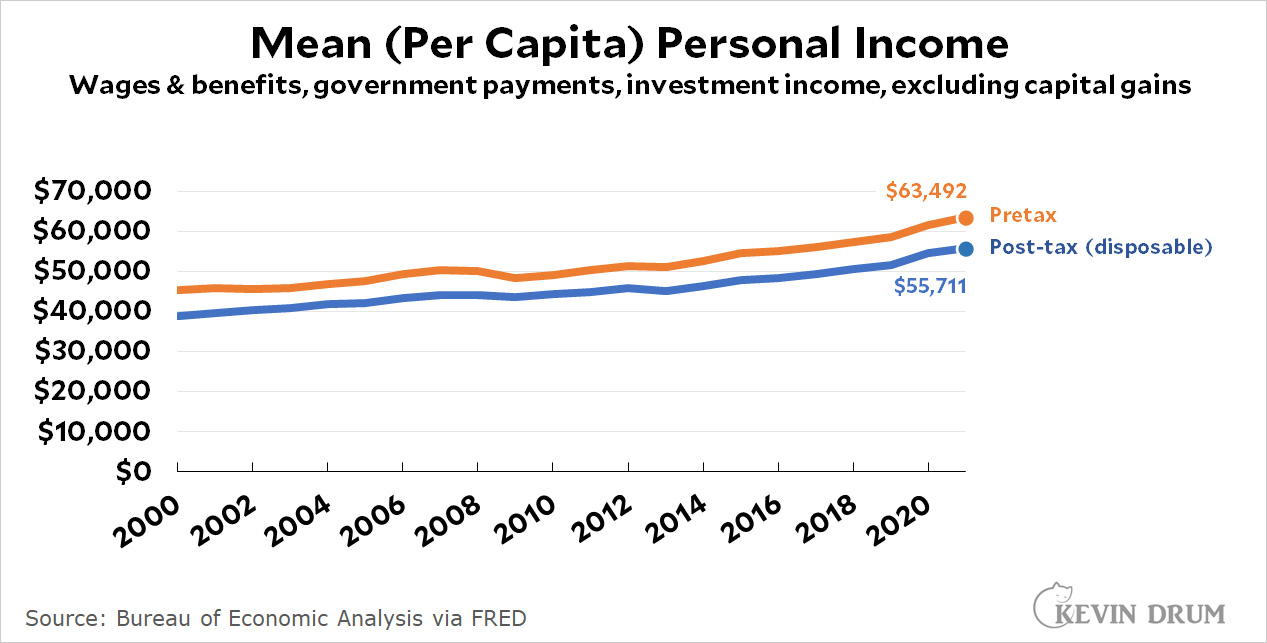

BEA income includes more items than the Census Bureau, and the BEA also provides a figure for disposable (after tax) income. But its big difference with the Census Bureau is that BEA uses mean instead of median income, which makes it much less valuable. The huge difference between the two is almost entirely due to this.

BEA income includes more items than the Census Bureau, and the BEA also provides a figure for disposable (after tax) income. But its big difference with the Census Bureau is that BEA uses mean instead of median income, which makes it much less valuable. The huge difference between the two is almost entirely due to this.

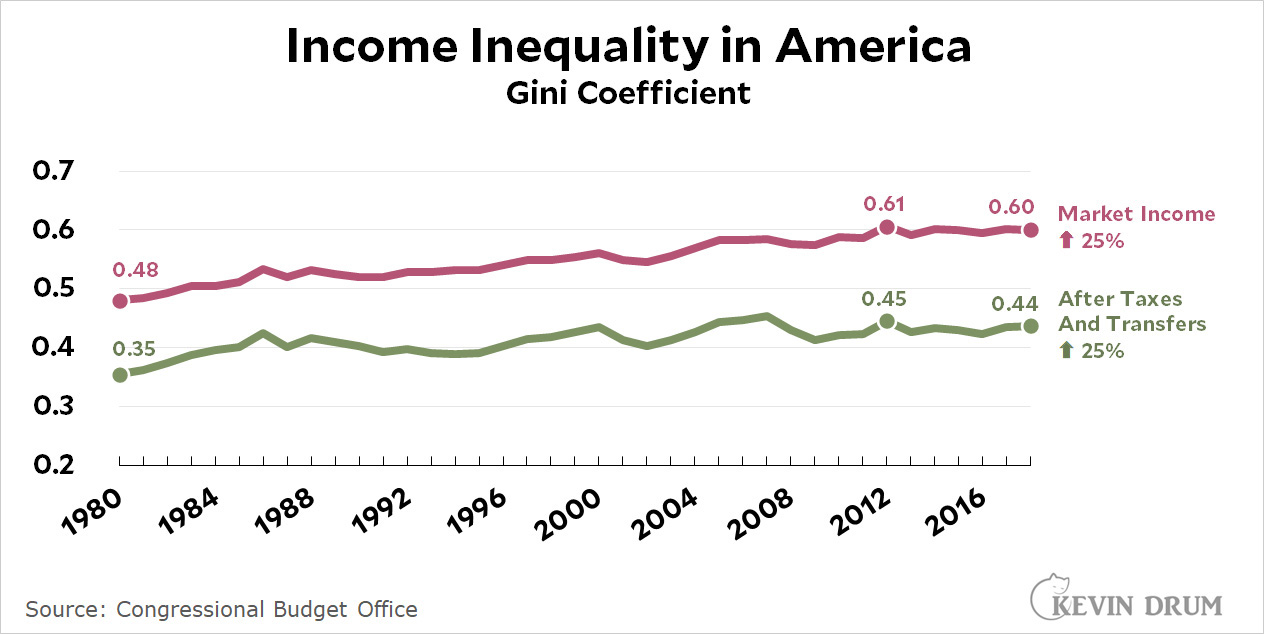

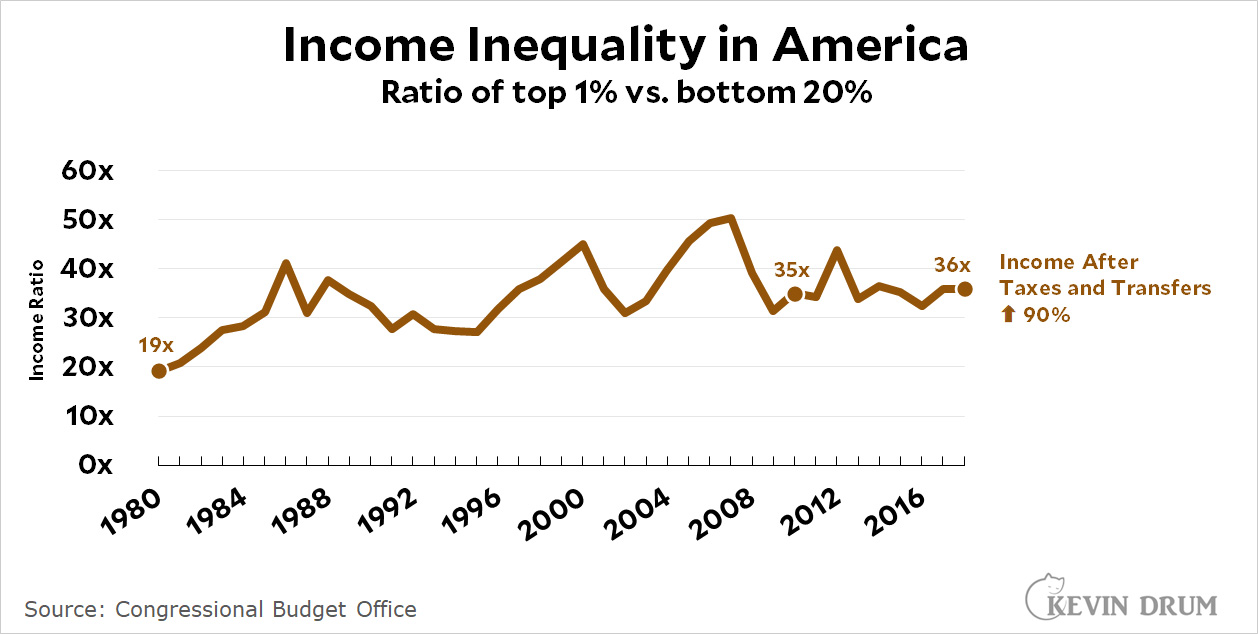

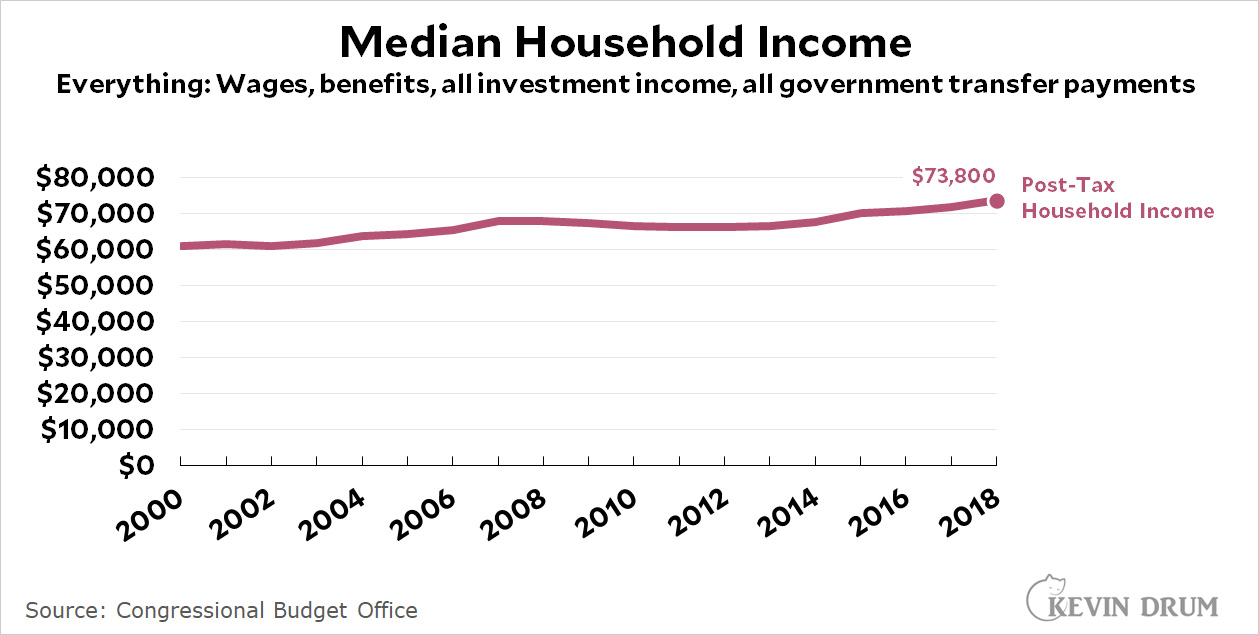

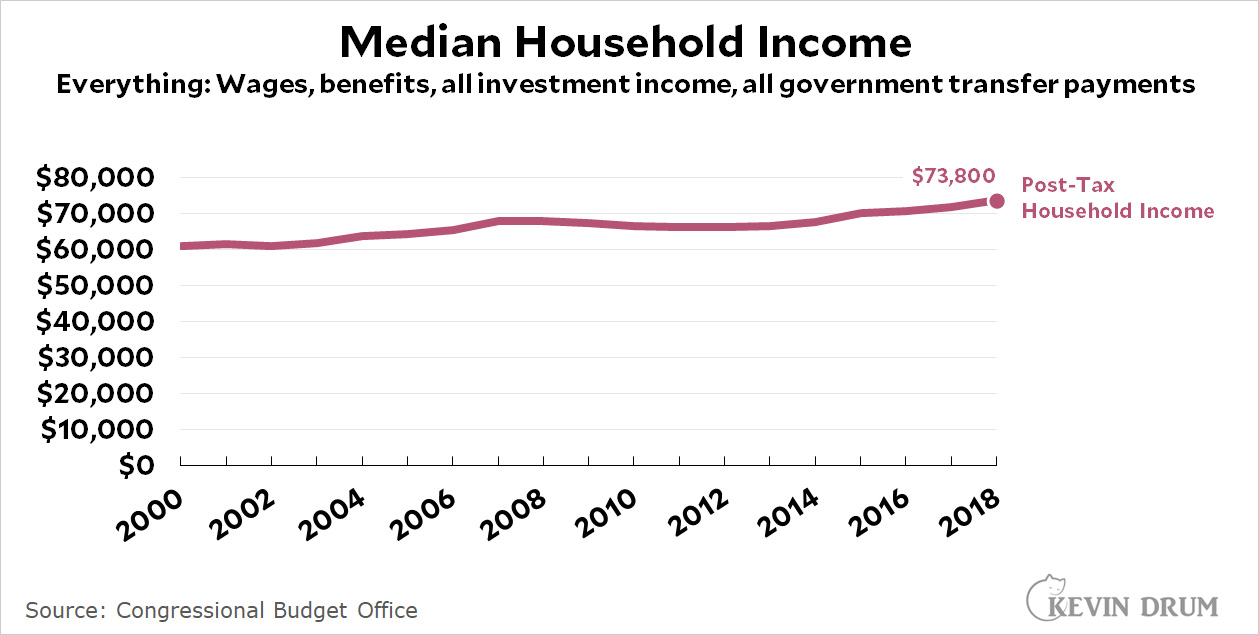

Next up we have an attempt by the Congressional Budget Office to account for everything, including means-tested government benefits and capital gains:

This is a good estimate of honest-to-God total income and taxes, and it's available as a median, so it's not skewed by the rich. Its big drawback is that it's not a regularly updated series. The last report to publish this information is from 2018 and there's no telling when they'll do it again.

This is a good estimate of honest-to-God total income and taxes, and it's available as a median, so it's not skewed by the rich. Its big drawback is that it's not a regularly updated series. The last report to publish this information is from 2018 and there's no telling when they'll do it again.

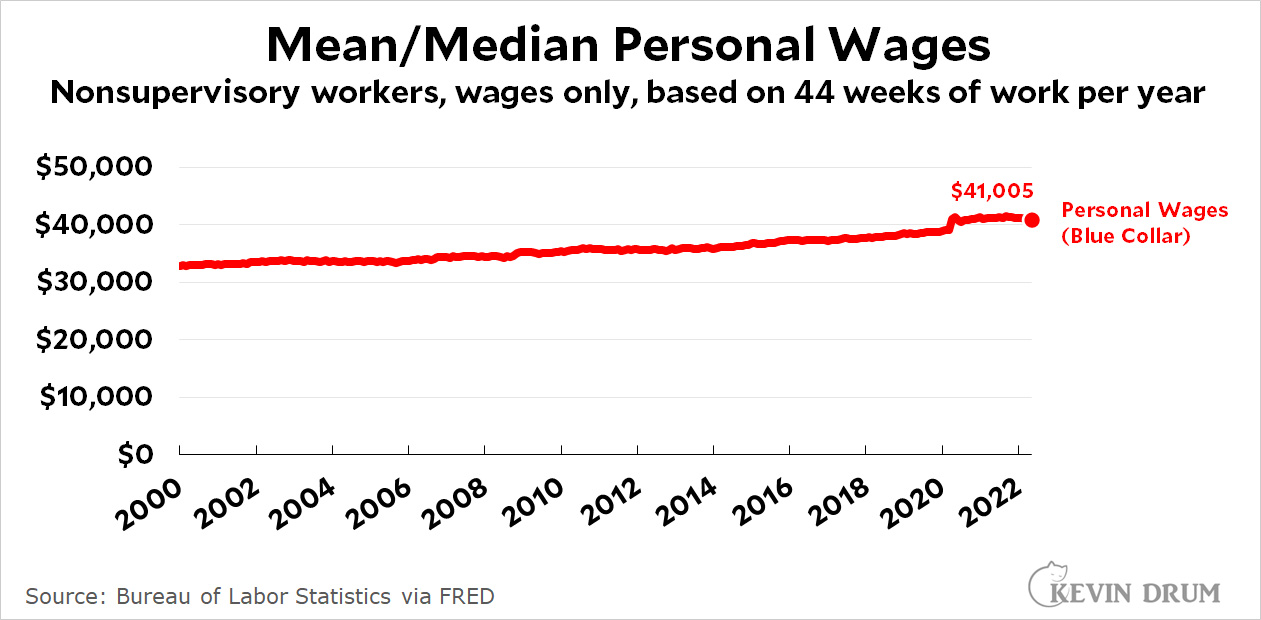

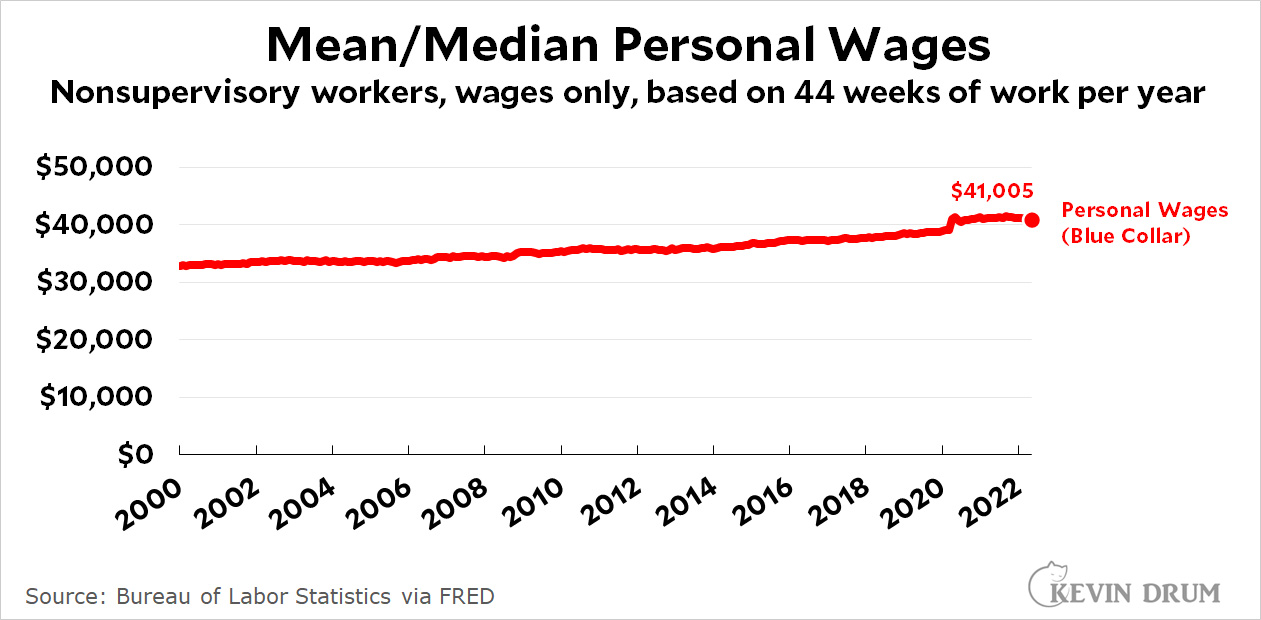

Finally, here's a dark horse entry from the Bureau of Labor Statistics:

This chart shows wages solely for production and nonsupervisory workers, and it's extracted by multiplying average weekly wages with average weeks worked per year. No managers or CEOs or Elon Musks are in here. Just blue-collar, salt-of-the-earth American workers.

This chart shows wages solely for production and nonsupervisory workers, and it's extracted by multiplying average weekly wages with average weeks worked per year. No managers or CEOs or Elon Musks are in here. Just blue-collar, salt-of-the-earth American workers.

The downside of this series is that it includes only regular cash wages and nothing else. The upside is that it's updated monthly for you impatient types. And while it's technically a mean, the fact that it lops off the top 20% means that it's effectively a median. The meh-side—could be good, could be bad, depending on what you're interested in—is that it measures income solely for the 80% of the country that's nonsupervisory.

And now for the twist: there's really not much difference between all these measures. If you compare the BEA's mean income to the Census Bureau's mean income, they're pretty close. If you compare Census personal income to nonsupervisory personal income, they're pretty close. If you compare Census household income to CBO household income, the difference is noticeable but not huge.

In other words, all of these estimates use a slightly different combination of income and taxes but they mostly wash out at the end. Roughly speaking, I usually stick with simple Census figures. If you want post-tax income, use the BEA figures to figure out tax payments and then subtract them from the Census figures.

NOTE: Some of these figures are available in both nominal and real versions. Some aren't, and you'll have to do the inflation adjustment yourself.